This is part of an ongoing collaborative series between Chalkbeat and THE CITY investigating learning differences, special education, and other education challenges in NYC schools.

When Eileen Bramer began as a school aide at Long Island City’s P.S. 111 in 1986, the job mostly involved doing whatever the teachers asked of her and remaining “more in the background.”

Three decades later, Bramer is still technically an assistant, but her role has changed dramatically: She and her fellow assistant teachers — also known as paraprofessionals — are now on the front lines of her school’s efforts to improve reading instruction.

“Every training has been offered to us. [We] are here to do the same thing that the teachers are,” said Bramer, a P.S. 111 graduate who now spends her days working one-on-one with first graders who are below grade-level. She reinforces basic reading skills, including step-by-step phonics lessons during which students learn the relationship between sounds and letters.

Deploying paraprofessionals to help teach reading is a core element of the school’s strategy to boost literacy, aided by the nonprofit Literacy Trust, which has helped train teaching assistants and other staff in nearly 120 schools citywide.

The stakes at P.S. 111 are high. Just under 18% of its students were proficient in reading last year, according to state tests. Though that represented an increase of about 5 percentage points from the previous year, it was still far below the city average of roughly 47%.

The school, which serves predominantly black and Hispanic students, faces strong headwinds: The vast majority of students at P.S. 111 come from low-income families. Roughly one in four children lack permanent housing, and about 40% are chronically absent, according to the most recent city data. The school runs a pantry in its basement, where parents can pick up essential food items, toiletries, and clothes.

Five years ago, the school was labeled among the city’s lowest-performing. It was placed in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s now-defunct Renewal turnaround program, which gave schools additional resources, and charged them with improving within a few years. Even so, education department officials reportedly considered shrinking or closing P.S. 111.

Principal Dionne Jaggon believes the school is on the upswing and partly credits an emphasis on rigorous phonics-based instruction. That approach is said to benefit struggling readers, but is not offered consistently at every city school.

[Related: A reading ‘crisis’: Why some New York City parents created a school for dyslexic students]

When P.S. 111 was in the Renewal program, the roughly $6,000 annual cost of the reading program was paid by the city. Now, even as the city has stopped subsidizing the program at P.S. 111, Jaggon finds it so valuable she’s paying for it out of her own school budget.

“It kind of trickled into the whole school,” Jaggon said. “We’ve seen more and more readers.”

Tiffany Zapico, the Literacy Trust’s executive director, said schools often find it beneficial to invest in training paraprofessionals, who are not required to earn a college degree but who often become certified teachers later on in their careers. “Oftentimes they want to do more, but they’re not necessarily given the opportunity,” she said.

City officials have tapped Literacy Trust to help train all of the 500 coaches in the city’s Universal Literacy program, which is meant to help every elementary school ensure students are reading on grade level by the third grade.

At P.S. 111, Literacy Trust has trained 23 staff members in a program called Reading Rescue. It’s a two-year process that involves eight full days of training, though participants begin to work with students after their second full day. Four times a year, Literacy Trust coaches come to the school to observe and offer feedback.

The trained teaching assistants work one-on-one with first graders who can recognize letters but are still below grade level; this year, 17 of the school’s 45 first graders are getting one-on-one help with reading for 30 minutes five times a week, school officials said.

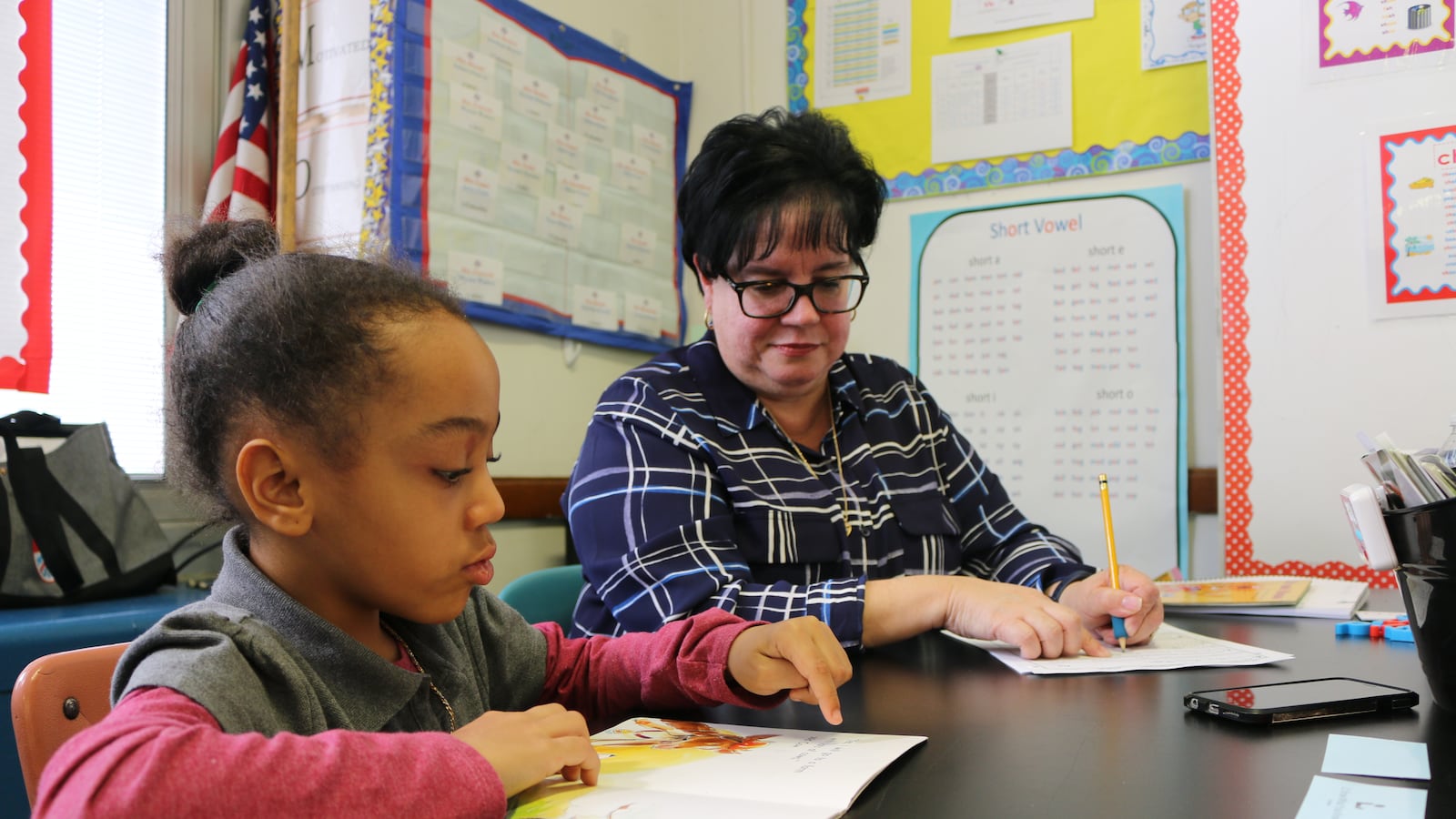

On a recent morning, Bramer offered Peyton Williams, a soft-spoken first-grader, a lesson that partly focused on how to identify short vowel sounds.

“This is a picture of somebody giving somebody a hug,” Bramer said, handing Peyton a tiny laminated square to place below the correct vowel letter. After thinking for a moment, Peyton put the small picture under the letter “o.”

“Let’s look at that again,” Bramer said, gently correcting her. “Say the sound with me: Uuuuuuugggh.” After a beat, Peyton correctly placed the picture under the letter “u.”

The entire lesson lasted 30 minutes and included Peyton reading two books out loud with Bramer looking over her shoulder, asking her questions about the plot, keeping track of words Peyton struggled to recognize, and prompting her to sound out words that tripped her up. At the end, Peyton collected a sticker of a princess and a paper bag of pretzels as a reward before returning to her regular classroom.

Bramer said she identifies with students like Peyton, who can become self-conscious about reading and shut down without individual support.

“I was a struggling reader — I definitely get how they feel and how you want to make them feel comfortable,” Bramer said. “I wish they had this when I was a kid.”