One in 10 New York City students lacked stable housing last school year, according to new data released Monday.

There were 114,085 homeless students at district and charter schools—numbers that speak to the scope of the crisis, even as they were down slightly over the previous school year, according to an Advocates For Children report.

“This problem is immense,” said Kim Sweet, executive director of Advocates For Children, in a statement. “The number of New York City students who experienced homelessness last year — 85% of whom are black or Hispanic — could fill the Barclays Center six times.”

The advocacy group compiled state education department data from the 2018-19 school year and found the number of students reported as homeless was down by 574 children year over year. It’s unclear what caused the minimal drop. The number of homeless students — defined as children in shelters or doubling up with family, friends, or others — has steadily increased since the 2014-2015 school year. Numbers released last year, which looked at the 2017-2018 school year, set a record-high for the number homeless city students and represented an increase of more than 3,000 homeless students from the previous year.

At least one-fifth of students were homeless in districts 5, 9, 12, and 23 last school year, the data show. During the same time period, at least 80% of students in these districts came from low-income families, city data show. (District 5 is in Harlem; 9 and 12 are in the Bronx, and 23 is in Brooklyn’s Brownsville neighborhood).

Not having stable housing can have a profound impact on student performance. It may prevent children from showing up to school consistently — or even having a consistent school — and from being engaged in class when they do attend. And homelessness can have an even bigger effect on younger students, a February report by the Research Alliance for New York City Schools showed.

This year, 29% of New York City students experiencing homelessness passed their state reading state tests, and 27% passed the math exam, according to state data — nearly 20 percentage points lower than their peers who live in stable housing.

Fifty-seven percent of New York City’s homeless students graduate from high school, according to Advocates — compared to 76% of all city students, homeless and not. The group also pointed to research showing a lack of a diploma is the “single greatest risk factor for homelessness among young adults.”

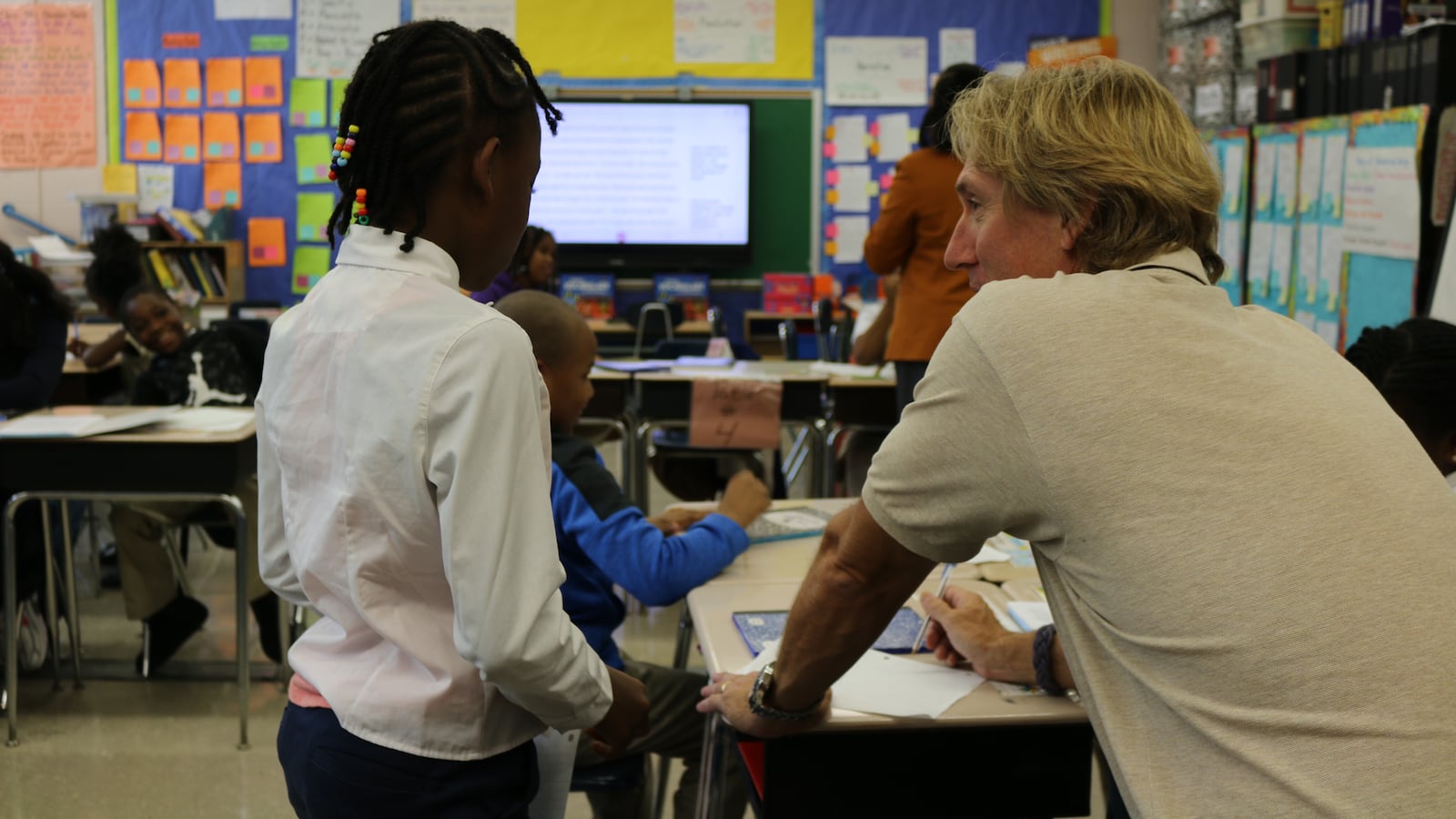

Researchers of the previous report from Research Alliance wanted to understand how schools were supporting children without stable housing and looked at five schools with high shares of homeless students who performed academically on par with all city students. They found that often, staffers took matters into their own hands: consoling families, joining them on visits to the city’s homeless PATH intake center, and helping pick up students so they could make it in time for free breakfast at school.

What was most helpful, staffers reported, was having non-teaching staff who focused on homeless students and having partnerships with community-based organizations.

“We’re making critical investments to meet the needs of students in temporary housing including hiring social workers, providing busing, and placing staff in schools focused on connecting families to community services and improving attendance,” said Miranda Barbot, a spokesperson for the education department, said in a statement. “We’re committed to serving these students and families by providing the programs and resources they need to have access to a continuous, high-quality education.”

As Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has grappled with the city’s homelessness crisis, the education department has rolled out certain programs to support those students — but critics over the years have pressed for more. This year the department planned to spend $12 million on new supports for homeless students. That investment includes hiring 100 new coordinators inside of schools with a high percentage of children who lack stable housing, providing more training for educators, and hiring 18 managers who oversee these supports.

And this year the city will pay for 100 “Bridging the Gap” social workers — 31 more than last fiscal year — at schools with higher concentrations of students in temporary housing. The boost came after a hard push from advocates and some elected officials, after the mayor again omitted funding for the social workers in his initial budget proposal.

In helping to support homeless students in school, Advocates for Children also pointed to the importance of the city offering yellow bus service to K-6 students living in shelters, increasing pre-K enrollment for children living in shelters, and offering after-school reading programs at certain shelters.

But they are pressing for more support, specifically to address chronic absenteeism. According to recent city statistics, only about half of families who entered shelters last fiscal year were initially placed in the same borough as where their youngest child goes to school. The group also cited data that nearly two-thirds of students living in shelters are chronically absent.

“We are heartened by the supports the City has added for students who are homeless, but now the harder work begins,” Sweet said in her statement. “With new leadership and school staff in place, the City must begin turning around educational outcomes for students who are homeless, starting with making sure students get to school every day.”