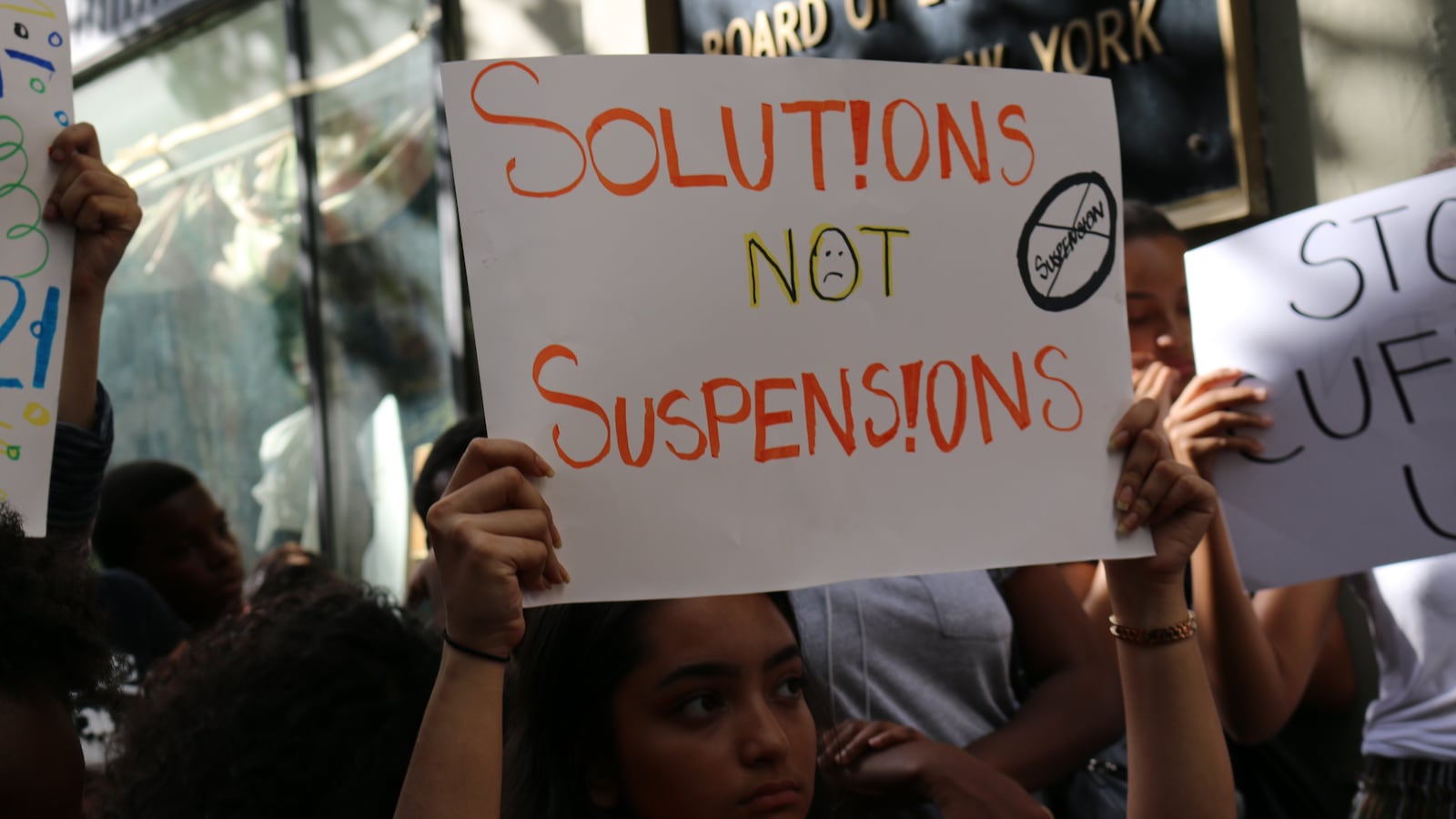

Recent changes to New York City’s school discipline code aimed at shortening suspensions and making discipline less punitive have garnered a lot of public attention. As a law student who works with students facing long-term suspensions, I believe those changes were desperately needed.

But I also see that another component of the school discipline process that usually flies under the radar needs to change: the ineffective web of procedures governing the school district’s suspension hearing process.

Public school students in New York City who are facing suspensions of over five school days — of which nearly 9,000 were issued last year — are entitled to an administrative hearing about their alleged misconduct. It’s basically a mini-trial at one of the education department’s five full-time suspension hearing offices, and students are entitled to the defense of an advocate.

That’s where I come in. Along with other law school students from around the city, I am trained to participate in these hearings on behalf of the accused student and their family. That means being fluent in the 40 pages of regulations laying out the rules around long-term suspensions, counseling students about their rights, helping families amass evidence, and arguing at hearings. In this role, I have come to understand that many of the rules and procedures, particularly around the burden of proof and no-contest pleas, do little to ensure fairness.

The changes made to the discipline code this summer — decreasing the number of days for which most students can be suspended — did not affect the rules governing suspension hearings. Among other things, these rules require schools to prove that a student did something suspendible using “substantial and competent evidence.” But after participating in dozens of suspension hearings, I still don’t really know what that means. How much proof is actually required? Certainly it’s less than proof beyond a reasonable doubt or clear and convincing evidence (as are often required in court). But how much less proof is it? To me, substantial evidence does not even sound like 50% certainty, and making that determination is left up to each individual hearing officer.

One student I worked with was accused of throwing a punch during a big school brawl. The school presented its evidence in the form of a dean testifying about what he saw during the fracas in the cafeteria. We then called as a witness the student who was actually punched. The student who was hit forcefully denied that our student was the one who hit him, but the suspension was upheld anyway based on the dean’s testimony.

That sort of outcome is not uncommon because of the low burden of proof required in suspension hearings. Right before starting a hearing for a different student who was accused of acting inappropriately toward a classmate, a hearing officer told me something surprising. He said that the suspension would be upheld if the school could present a single credible witness — regardless of however much independent evidence to the contrary was also presented.

The extremely low burden of proof is not the only issue I have encountered. School officials, and even some hearing officers, actively encourage families to plead no contest. That means the school’s allegations are accepted as true and the hearing office determines how long the student should be suspended. There is no hearing and no presentation of evidence.

Pleading no contest can make sense for students who don’t want to sit through a hearing or who have already served all or most of the suspension days that they are likely to get. But it often has a host of unintended consequences as well, like exposing students to harsher future discipline, negatively impacting their probation, and eliminating any chance for them to tell their side of the story. I have encountered families so worried that having a hearing will upset the school and result in retaliation that the student just pleads no contest. Others feel coerced after they are told that a student can return to their school more quickly if they agree to forgo the hearing.

Sometimes the dynamic feels more nefarious. A principal once told me that he knew our student did what he was accused of: taking a swing at another student. That principal viewed having to spend a morning at the hearing office as a waste of his time. So here’s what he said: He would ask for a 180-school day (one year) suspension if we “insisted on” having the hearing — or he would instead request that the student return to school after just a few days if he pleaded no contest. That type of threat is not allowed, but the student’s family did not feel like they could justify the risk of having a hearing.

The risk for coercion and confusion is why education department regulations forbid school officials from even discussing entering a no contest plea with families. That conversation is supposed to be left to the hearing office, so that students and families don’t feel intimidated and actually understand their rights before making a decision. But, in my experience, hearing offices can be indifferent about complaints by students and parents regarding school officials’ behavior during the suspension process. And very few families have access to advocates who will inform them of their rights and who feel comfortable navigating the complicated hearing process.

And there can be coercion at the hearing offices too. I once saw a hearing officer angrily insist that the accused student’s mother state a reason “for the record” for having a hearing before we could begin one, even though no reason is required. The student’s mother responded: “Because my son didn’t do it.”

Hearing officers also stress that law enforcement can subpoena a transcript from suspension hearings, sometimes seeming to imply that students might be better off pleading no contest for that reason. But I’ve never seen a hearing officer tell a student and their family that a no contest plea might also be used against them — something that I have seen happen in court in juvenile delinquency proceedings when the student’s decision not to challenge the school’s account is interpreted as accepting it.

The looming threat of police involvement also can lead to no contest pleas instead of hearings. A principal – different from the one I mentioned before — agreed to a meeting with a student and his mother the day after a fight. The student’s mother thought they could all work through the situation together. But when the family was finally brought into a school conference room after a long wait, the principal came in to say the NYPD was also there: to arrest the student. It was a setup. And the student’s subsequent ability to tell his side of the story at a suspension hearing was severely limited because of the pending criminal case. Pleading no contest seemed like the safe thing to do. Something is seriously wrong when school officials become agents of the police. The Department of Education should be hiring more social workers, not paying for thousands of school safety agents and doing the NYPD’s work for them.

The students and families I have advocated for have all wanted the same thing: fairness. Their resiliency in the midst of a harsh and often hostile system has inspired me to stick with this work even though I rarely see the outcomes I hope for. But based on what I have seen, the current web of procedures doesn’t actually guarantee fairness.

Being suspended means missing class at your normal school and being labelled a “bad kid” before the rest of the school community. It can also be a first or second step along the school-to-prison pipeline. Students deserve a process with a real burden of proof and the right to have a hearing without being pushed to plead no contest. The recent changes to the lengths of most suspensions make for a good start, but the change should not end there.

David Altman is a law student and an advocate with the Suspension Representation Project, and its former deputy director. SRP is a coalition of law school students who advocate alongside students and their families at superintendent’s suspension hearings in New York City. Any views expressed here are his alone.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.