A major initiative employing reading coaches to help teachers improve instruction showed small gains in achievement, according to an education department review of the city’s Universal Literacy Program released Thursday.

Education experts had mixed reactions on the modest improvements in the report, which also detailed mixed reactions from school administrators on the roles of reading coaches and the need to build trust with teachers.

The program, a key part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s education agenda which has cost a total $130 million since fiscal year 2018, aims by 2026 to get every student reading on grade-level by the end of second grade. While the program now reaches all schools, this report studies the 2017-18 school year, when 304 schools had access to coaches working with teachers individually and in groups on the most effective ways to teach children how to read.

The study revealed that students whose teachers spent more time with coaches notched slightly higher scores on a reading assessment known as the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test, or GMRT, compared to their peers at schools that did not have such coaches, according to the report from the education department’s Research and Policy Support Group.

“When looking across these classrooms, students of teachers who received coaching grew more than students of teachers who didn’t; the more periods of coaching the teachers received, the more students’ scores grew, on average,” the report said.

Students at 110 schools that had reading coaches saw a 23-point increase on the test from the fall of 2017 to the spring of 2018, while at schools without those coaches, scores grew by 20.6 points, the figures showed. Reading comprehension scores, in particular, were the only “statistically significant” highlight, according to researchers. At schools with access to coaches, comprehension scores grew 22.5 points compared to 18.9 points at schools where teachers were not being trained.

Notably, overall scores for schools that had coaches for a full year scored similarly to their peers at schools that were newer to the program.

Chancellor Richard Carranza, along with some literacy experts, celebrated Thursday’s report.

“I’m thrilled by the positive impact it is already having on our students and schools,” Carranza said in a statement. “I am confident that this initiative will continue to make a difference for our students and schools in the years to come.”

The city’s school system has no systematic approach, according to experts and educators, on teaching thousands of students with dyslexia how to read, as previously reported by Chalkbeat and THE CITY. In response to that criticism, the education department, pointed, in part, to the Universal Literacy Program and its focus on reading coaches as helping students with disabilities. The report says reading coaches spent about 60% of their time with teachers in classrooms that served students with disabilities.

“Experts agree teacher coaching makes the strongest difference in literacy for children,” Maryanne Wolf, the director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, said in the education department’s press release. She was “delighted” to see Thursday’s report.

But after reviewing the report, Susan Neuman, a professor of childhood and literacy education at NYU, said she doesn’t see reason for celebration yet because of the small overall changes.

“While I’m delighted that they’re taking this seriously, I think it’s not sufficient,” said Neuman, the former U.S. assistant secretary for elementary and secondary education. “And I think they should not be excited nor should they call this a substantive change.”

Neuman said that having a strong, uniform reading curriculum across individual districts would have a greater impact on student achievement versus just reading coaches. Schools in New York City can choose from education-department recommended curriculum, but they are also free to implement the model they want.

The report also highlighted how schools are grappling with reading coaches. Notably, a challenge cited by a third of surveyed respondents was that the coach was spending too much time out of the building for professional learning. Using data from coaching logs, the report found that coaches spent 42% of their time in schools with teachers, while another 25% of their time was spent on planning.

Another challenge, cited by a quarter of respondents, was that teachers were resistant to working with a reading coach, the report said. It noted that coaches “need to gain the trust of teachers” for the work to be effective.

In surveyed responses, 59% of building leaders said they were satisfied or highly satisfied with the Universal Literacy initiative. Nearly 19% said they were unsatisfied or highly satisfied. The rest fell in the middle.

The report noted that nearly 70% of administrators at schools in the second year of the initiative rated the program highly, making it possible that schools newer to the program are adjusting — or that those who took time to respond were opinionated on both ends of the spectrum.

In open-ended responses, one administrator wrote that their coach was an “essential” part of the team, while another said their coach has helped struggling teachers. A “small number” of administrators wrote critiques, according to the report, including one who suggested that there was a disconnect between what the school needs and what the literacy coach is able to offer.

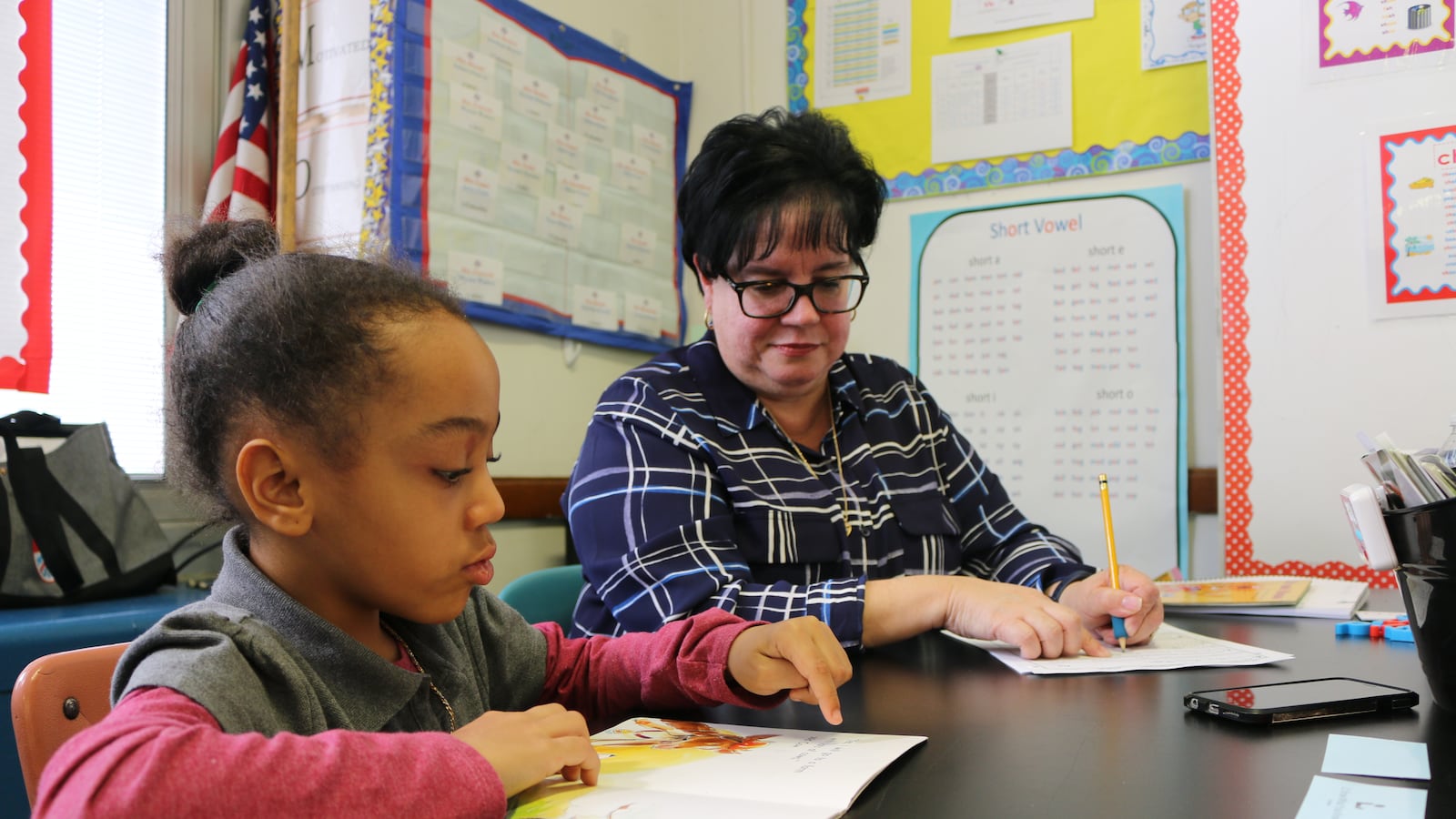

A reading coach comes three days a week to help teachers at P.S. 676, an elementary school in Red Hook, said Principal Priscilla Figueroa. School leaders said the coach brings more structure to reading instruction and more support for the school’s existing reading program.

“Any school would benefit from a coach — I’m definitely happy we have a coach,” Figueroa said.

Alex Zimmerman contributed to this report.