When 16-year-old Sebi Smith arrived to class at the Brooklyn Transition Center on a recent Wednesday, he didn’t sit in a row of desks or face a blackboard.

Instead, Smith and a handful of classmates took out their plastic barcodes and “clocked” into a classroom that was built to look and feel like a CVS drug store — right down to the Hallmark card aisle and Ariana Grande soundtrack.

One student started dusting the shelves, while two others practiced making change with plastic coins. Smith, meanwhile, grabbed a circular and began plucking items off the shelves: hydrogen peroxide, cotton balls, and paper towels.

“Did you get any laundry detergent?” teacher Miranda Haraughty prompted, sending Smith back into the maze of aisles to find it.

These tasks may seem simple, especially for high school students. But they’re not for those at the Brooklyn Transition Center, part of a network of schools known as District 75 that only serve students with the most pronounced disabilities. These are skills that can involve potentially challenging social interactions, lots of outside stimulation, and mental math. And the stakes are high: If students don’t master the basics, school officials worry they may be more likely to live isolated from their communities and unable to hold down jobs.

“A weird unofficial motto is, ‘No one sits on their couch’” after they graduate, said Courtney Rattenbury, an assistant principal who has worked at the school for over a decade.

Like most District 75 students, those at the Brooklyn Transition Center typically have cognitive disabilities, autism, sensory issues, or severe emotional needs. They typically stay in the school system until age 21 and aren’t eligible for a traditional high school diploma.

“We want them to be out in their community and fully engaged, no matter what that means for them,” Rattenbury added, whether it’s a job or a supervised day program that allows them to spend time outside of their homes volunteering, exercising, and reinforcing life skills such as cooking or money management.

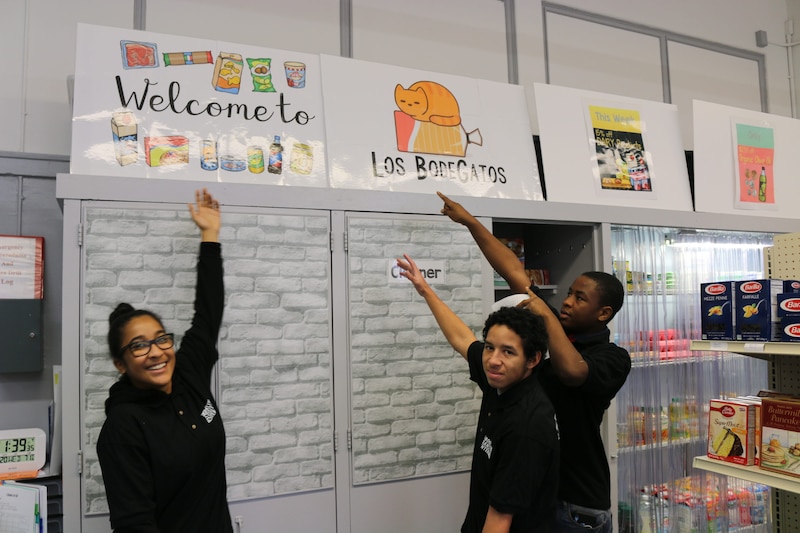

To reach that goal, the school has expanded opportunities for students to learn job skills without even leaving the building, creating a series of “learning labs,” including the replica CVS, a bodega, and a full-service diner. As students build experience, they slowly transition from traditional classroom instruction to spending more time in the learning labs. Eventually, school officials place students in internships or jobs for much of the day that often match the learning labs students have worked in.

The learning labs serve as a chance for students to practice in advance of working at places like Modell’s or Shake Shack. Before the school invested in the labs, with help from a $25,000 grant from the Walentas Family Foundation, principal Regina Tottenham said students often struggled to adjust to the workplace.

“You take a student who had been in a self-contained class with the same teacher for years, and we pluck them out because they’re 18 years old, and we put them in a full-time worksite — and they’re like, ‘Holy Hanna, what is this?’” Tottenham, said. It was too abrupt, especially for students used to routines, or who may struggle to manage new social interactions with real customers.

The learning labs also give students a chance to figure out their interests before they receive a job placement. A student may not like working at “Bodegatos,” a learning lab modeled after a bodega, but enjoys working with food and wants to cook in the school’s new diner.

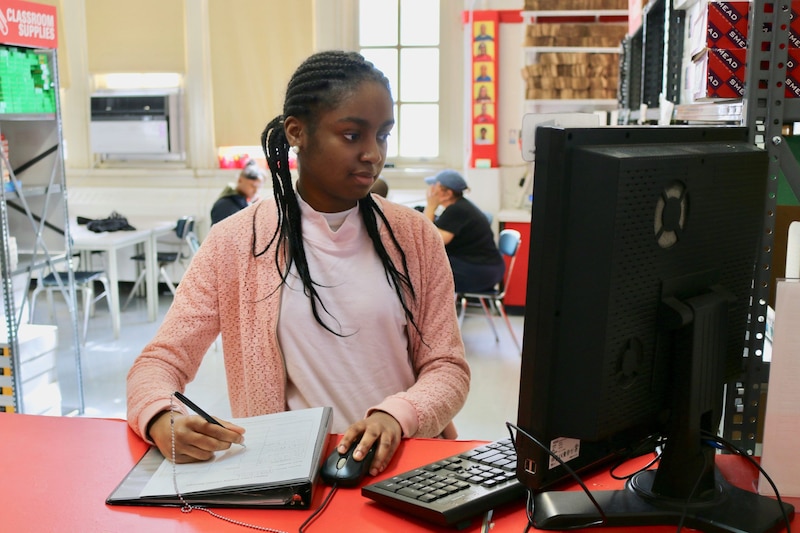

In another part of the building, students work at a mock Staples — dubbed “Paper Clips” — where they serve as a logistics center for the entire school. On a recent afternoon, 16-year-old Gabriella Logdell pored over a Google form that listed orders from teachers for items, such as copy paper, binders, or sanitizer. Later, students go through the process of finding the products, completing an invoice, and delivering the items directly to the teacher.

Twice a week, Logdell helps clean and stock a real Staples in Greenpoint through a school program, which she said feels more comfortable because of the time she’s spent practicing in a lower-stakes environment. Her ultimate goal is to work with animals.

School officials also said they have worked to include students with the greatest needs, who typically occupy the fourth floor to reduce the chance they’ll wander out of the building. The school launched a “buddy” program where those students — who have more serious cognitive delays or autism — help out in the learning labs with peers who have fewer needs. In the cafeteria, some of the higher-need students help their peers sort their trash from recycling and food scraps, which are collected for composting.

Across the room, a group of English learners staffed a snack kiosk, an effort to give them practice honing their conversation skills. “This store helps me get better at talking to people I don’t know,” explained Henry Guzman, whose parents emigrated from Mexico and Ecuador, after supplying Tottenham with a granola bar.

About 90% of students at the Brooklyn Transition Center are black or Hispanic and most come from low-income families, city data show. Asked about funneling already vulnerable students into low-paying fields, Tottenham said there’s no shame in low-skilled labor.

“We still push them to their limit just like every school would,” she said.

In fact, other school leaders in District 75 have visited the program to learn more about their approach.

At the Brooklyn Transition Center, school officials said they work intensively with parents seeking services for their children to help them navigate complicated networks of day programs, funding streams, and government bureaucracies.

“It’s incredibly confusing and you really have to be on board with all of your parents,” Tottenham said.

Schools are legally required to help craft plans for each special needs student to help them transition to adulthood, though advocates have said they often fall short. The education department has opened centers in every borough in recent years staffed with experts who can directly help students with disabilities plan for life after high school, while also training school personnel on how to guide families through the process.

One potential outcome is for a student to land a job at the education department. Some 175 students from District 75 have been hired as teacher aides over the past five years, including 20-year-old Phoenix Holly. He now works at the Brooklyn Transition Center, keeping students on task, taking attendance, and helping input student information into the city’s special ed data system.

As a person with autism, he said it feels important to give back.

“I see myself in them,” he said. “If I can go through what I went through growing up, then anybody in a District 75 school should be able to do the same.”