As New York’s state lawmakers make their way back to Albany for the next legislative session on Jan. 8, they’ll be mulling two big New York City education items: school funding and specialized high school admissions.

In a way, both are perennial issues.

State lawmakers annually argue over how much money should go toward school districts — the largest expense of the state government. But this year, officials are expecting a $6 billion deficit and that’s likely to make for a thornier battle with Gov. Andrew Cuomo over increasing Foundation Aid — a funding formula that sends extra dollars to high-needs districts like New York City.

Increasing diversity at the starkly segregated specialized high schools, where admission is based on a single test, heated up a few years ago. The concern over how few black and Hispanic students are offered spots at the schools opened a Pandora’s box about the admissions exam. The city’s plan to eliminate the test, which needs state approval, has failed twice in Albany. A group of lawmakers now want to repeal the law that mandates the admissions test – taking the matter out of the state’s hands entirely. But there are still efforts to preserve the test.

Here’s more about these two issues.

Education dollars and Foundation Aid

When the state sends money to New York school districts, a majority of it is funneled through Foundation Aid. A lawsuit prompted the creation of the Foundation Aid formula a dozen years ago, but since then it has largely not been funded to the level promised.

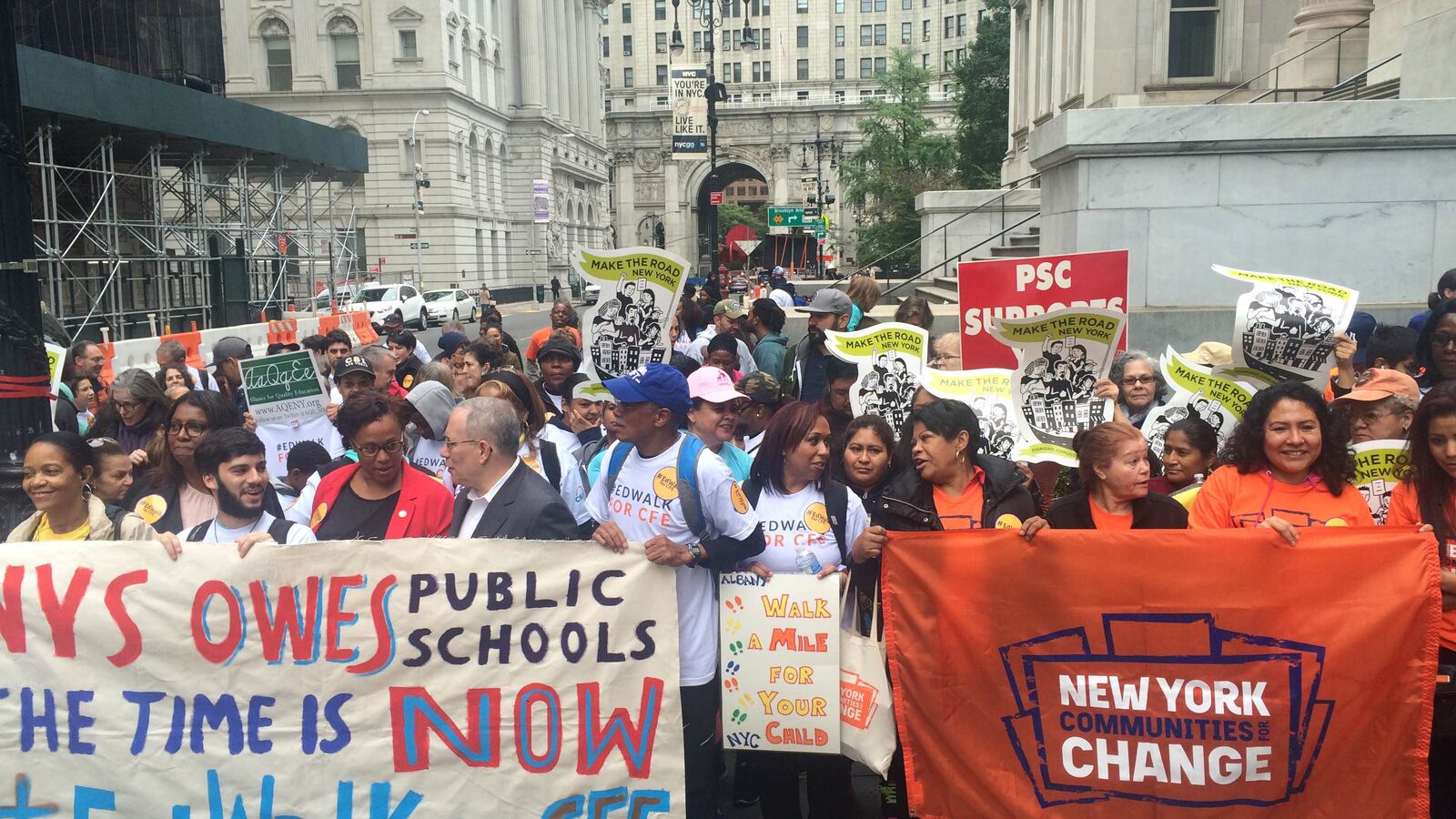

State education officials, who this year are asking for a $2 billion increase in education dollars, contend that the state still owes districts a total $3.7 billion in Foundation Aid — not counting for inflation — and that New York City is owed about $1.1 billion of that. Cuomo, who has increased education spending over his time in office, has said the Foundation Aid lawsuit is a long-settled matter that doesn’t bind him to any set spending boost.

Yonkers Democrat Sen. Shelley Mayer, who co-chairs the Senate’s education committee, held a series of discussions throughout the state this fall to examine whether the 12-year-old formula should be tweaked. In New York City, advocates and city officials argued that the state must fund the formula to promised levels before changing it.

How to tweak the formula is a tough conversation to have, said Sen. John Liu, chair of the Senate’s New York City education committee, because it could affect different districts in different ways.

“I think from our conference’s point of view, getting more — substantially more — Foundation Aid continues to be the top priority, and then trying to build steps to address the inequity in the formula,” Mayer said.

In their legislative proposal, the Board of Regents have asked for $1.2 million to help pay staff and consultants to research the formula. State officials “should be taking the time” to think through changes and build public consensus, said Bob Lowry, deputy director of advocacy and communication at the state’s Council for School Superintendents.

But as state lawmakers lobby for more education dollars, the state is facing down a $6 billion deficit, the largest in nearly in a decade. That will likely make fighting for extra school dollars a tough battle, especially as the governor prefers not to increase spending more than 2% from the previous year.

“We will fight for [Foundation Aid] again this year,” said Brooklyn Assemblywoman Jo Anne Simon, who sits on the Assembly’s education committee.. “Very often for years, the Senate majority, which was in Republican control, was more hostile to that. We have a different partner in the Senate now, and that will be helpful. We are, however, facing a pretty significant shortfall in the state.”

Specialized High Schools

The controversial specialized high schools admissions exam is required under state law for three of the city’s most coveted schools, Brooklyn Tech, Bronx Science, and Stuyvesant.

But this year, attention could substantially turn to getting the state out of the matter completely by repealing Hecht-Calandra, the section of education law that mandates the exam. Rep. Charles Barron, a Brooklyn Democrat who sponsored a bill to get rid of the test, told Chalkbeat in October that he and a group of lawmakers are now turning their support to that repeal.

That effort comes as Mayor Bill de Blasio has backed away from his plan to scrap the exam. His plan — to admit the top 7% of students at each city middle school — was part of Barron’s bill that never made it out of the Assembly. Studies have shown that the city’s plan would have almost immediately increased the number of black and Hispanic students at those schools.

“Whether it happens this year or not, I don’t know,” said Simon, one of the lawmakers who has supported scrapping the exam and is now behind the effort to repeal the law. “I do think that just a repeal is a very viable approach and puts the decision-making where it belongs, and that’s with the city.”

But even this effort will prove tough to build support.

Liu does not support repealing Hecht-Calandra, saying, “I don’t ever support abdicating responsibility.”

He has called de Blasio’s plan to scrap the admissions test a non-starter because he believed the rollout of the plan was a racist effort to shut out Asian voices. The mayor, and even supporters of the city’s plan, have said that the rollout — which immediately sparked opposition from Asian families who felt they’d be elbowed out of admissions — was flawed.

“It’s hard to think [a repeal of Hecht-Calandra] will go very far, and the result of that would be letting de Blasio have what he wanted in the first place, which was a really bad idea,” Liu said.

For years, that test has been at the center of a controversial debate over how to make the schools more racially representative of the city, where 67% of students are black and Hispanic, but this year, just 10% of specialized high school admissions offers went to those same students. In contrast, 51% of offers went to Asian students and nearly 29% went to white students.

While the city has expanded public test prep and efforts to make underrepresented communities aware of the exam, the schools have remained starkly segregated.

Opponents of the test charge that those who have more access to test prep gain a leg up to admissions, and argue that a test is an invalid way to measure how well a student will do once they enter the school. But those who support the test say it is a race-neutral way to admit students, and that the real problem is lack of robust education at the elementary and middle-school level.

The pro-test, well-funded Education Equity Campaign, backed by cosmetics billionaire Ronald Lauder and former Time Warner and Citigroup chairman Richard Parsons, has spent at least $1 million on lobbying, advertising, and offering free test preparation to students.

The group plans to continue lobbying lawmakers and supports a bill from state Sen. Leroy Comrie aimed at creating 10 new specialized high schools. The bill also calls for a commission to recommend improvements to middle schools, expanding public test preparation for every sixth and seventh grader, making it standard for every eighth grader to take the SHSAT (with the choice to opt out), and opening more gifted and talented programs.

Other issues to keep an eye on

New York City this year reached a state-imposed cap on how many new charter schools could open within the five boroughs. Democrats who opposed expanding charter schools took control of the state Senate last year, so there’s been little appetite to pass a law to lift that cap.

For months now, Liu said he’s heard from multiple, minority-owned charter schools who want a space to open up in New York City. He’s “doubtful” that lawmakers want to lift the cap.

“There are a large number of organizations and existing charter schools that are looking for relief,” Liu said. “The discussions have been going on for months now post-session, and the discussions aren’t going away just because of the new session in January.”

A high priority for Sen. Mayer is improving civics education, she said. Last year, Mayer sponsored an unsuccessful bill to create a yearlong civics fellowship with a stipend for students between high school and college, exposing them to state and local government.

It’s tough to get support for bills that push for more civics education because they typically require schools “to do more,” Mayer said. But she believes she has increasing interest from the public.

“I would say there is tremendous interest in the state, not just social studies teachers, but many seniors no longer involved in schools who are concerned that our graduating students don’t know enough about our democracy.”