Christina Potenzone went to graduate school to become a science teacher.

Though many new teachers feel overwhelmed when they enter a classroom, Potenzone said she felt wholly underprepared to meet the steep challenges of her seventh graders when she landed three years ago at I.S. 96. Students at the southern Brooklyn school speak 56 different languages and dialects, and about a quarter of them are learning English as a new language.

“As a first-year teacher, I was thrown into it, and thought, ‘What do you mean they don’t understand?’” Potenzone recalled.

Many subject-specific teachers, like Potenzone, aren’t extensively trained on teaching students who are learning English for the first time despite the sometimes intensive needs such students might have. Last school year, just 4% of New York City’s middle-school students who are learning English as a new language passed their state reading tests, according to state data. Additionally, about 41% of the city’s English language learners graduated on time last year, compared to 77.3% of all students.

Three years later, Potenzone says she feels more confident.

Her school, along with 16 others in southern Brooklyn, received a chunk of a $1.5 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, to train teachers on helping their students gain a better grasp of the language and create a network for teachers to share their work with each other. This work is expanding with a five-year $13 million grant from the foundation announced last month for 45 middle schools that serve “a concentration” of English language learners.

Education department officials are still determining which schools will receive the funds that will pay for on-site coaching, professional development, and other resources such as materials to measure whether their work is helping students become more proficient in English. (The Gates Foundation is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

“We needed to figure out how to teach the teachers,” said Erin Lynch, principal at I.S. 96, said of their work.

I.S. 96 took an early look at how far the money can go. With a total $30,000 from 2016 to 2019, her school developed small-scale strategies to help students learn key vocabulary words and encourage them to practice English more in the classroom, such as equipping them with desk-taped visuals that provide them with certain sentence structures.

School leaders claim to see a difference in how students are grasping the language. An average 74% of students in classes where teachers were using the newly developed techniques noticed better scores on their New York State English as a Second Language Achievement Test, which tests English proficiency. That compared to 46% of students who saw improvements, yet were not in such classes.

But the work is challenging and takes time. The students continue to struggle on state reading exams, though they pass at higher rates than their middle-school peers citywide.

In 2017, after the first year of the grant, just seven — or 4% — passed the state reading exam. (That’s the same percentage as the citywide average.) Two years later, the number inched up to 12 students — or 7 % — who passed. The state, however, has said scores can’t be compared from 2017 because the test has changed.

The goal of the new round of grant money will largely build on the work that came out of the original grant. It’s aimed to help schools develop solutions to problems they’ve discovered with instructing English language learners. It will also focus on bolstering a network for teachers, who will meet four times a year and will share their best practices with other educators who work in nearby schools, called Instructional Networks.

While teacher preparation programs in the state require some credit hours in language acquisition, it’s not nearly as extensive as earning a certification in Teaching English to Students of Other Languages. Last year the state moved to require more credit hours in language acquisition for New York teacher preparation programs.

“It’s hard for the administration,” Lynch said. “We want to support them, but it’s difficult because we are not experts in that area.”

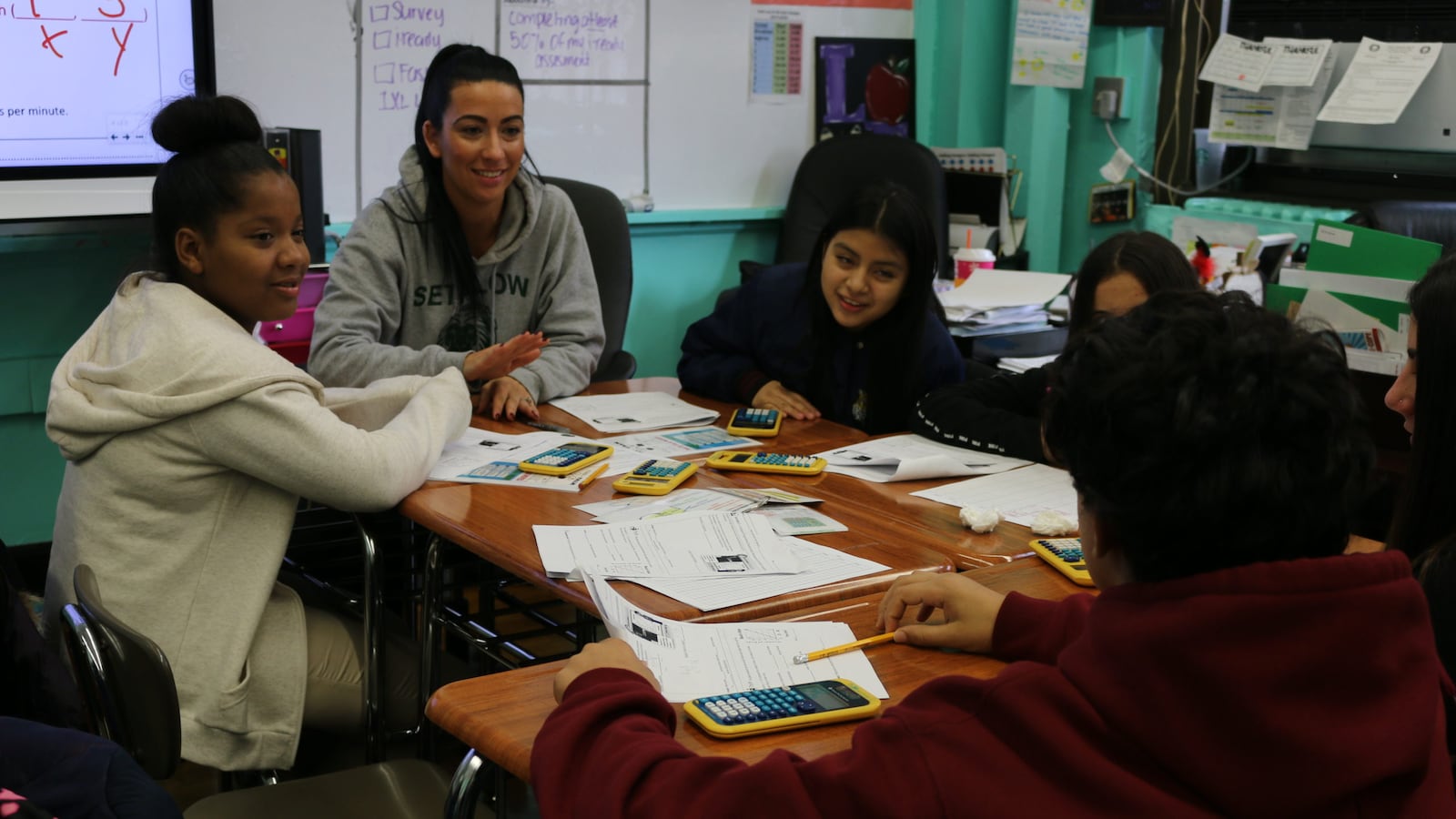

At Lynch’s school, officials developed a team of mostly content-based teachers, like math and science, who are led by “coaches,” or teachers who are trained on best practices in teaching students learning a new language. The team brainstormed about their challenges in helping English language learners become proficient. Over the past three years, the team has tried to find ways for students to practice the language more in the classroom, such as explaining to their deskmate why they solved a math problem in a particular way. Teachers often observed that students learning English were too nervous to assert their opinions in class, in fear of messing up.

The team has learned a lot through trial-and-error.

One example: last year they decided to develop guides with sentence stems, with words like “I agree” or “I disagree” on desks for students. Then, teachers in content areas would ask students to turn to their peers and explain an answer to a problem they were talking about in class.

But as teachers in the test classrooms monitored their students’ conversations, they noticed that the children new to English were not going far beyond saying “I agree” or “I disagree” — they weren’t explaining their answers. Teachers reported back, and the team made a tweak – “I agree because.” That, school leaders say, has encouraged more students to have longer conversations in English, and it’s now used for students schoolwide.

School leaders said their most significant achievement was creating and integrating visuals, such as memes, into vocabulary lessons. This gave students learning English a stronger grasp of a word that could be used and understood in different ways, such as “support,” which is both a verb and a noun, said Assistant Principal Ivelisse Fañas.

“I think a lot of these strategies — implementing all of that — just takes time to see,” said Diana E. Cruz, director of education policy at the Hispanic Federation, an advocacy organization that focuses in part on education initiatives.

“I like the idea that they are doing a lot of trial-and-error and really looking and making the time to see, ‘Ok, is this working? Is this not?’”

This grant and its specific goals are especially worthy because there is “never enough money” focused on improving learning for multilingual learners, she added.

But the grant leaves out an important aspect, Cruz worried. It fails to include an effort to reach parents of these students and increase their involvement in the school by bolstering translation services.

“There’s a lot of reasons why parent engagement can be low, but a lot of times it’s because parents are like, ‘Well, I just don’t know, I don’t know who to talk to,” Cruz said, acknowledging that some schools are able to do that work on their own. “When we think about the students who are multilingual learners, we think about families. It’s the students and the parents.”