Sardar Khan talked rapidly one morning about why students should not be required to take the Regents, New York’s high school exit exams.

“What teachers do is they rush through the entire school year just because they want to cover all the topics that’s on the Regents. They skip a few topics and don’t spend enough time on it to the point where you completely understand,” Khan, a 17-year-old senior at Manhattan’s Union Square Academy, said during an interview last month. “It’s like a competition or a race towards the Regents.”

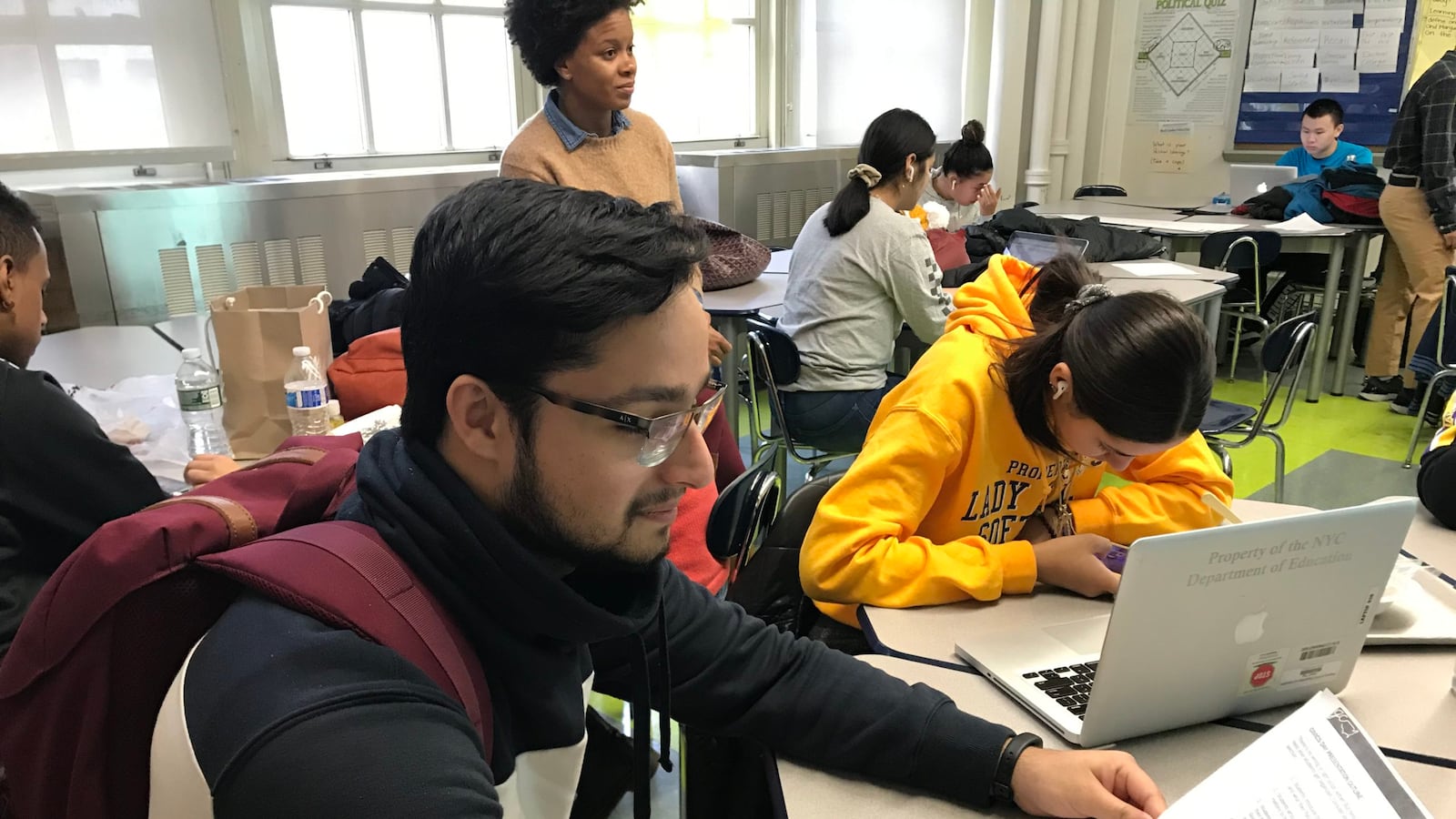

Khan is an unlikely education activist, admittedly never paying too much attention to school policy before this. But his AP government class spent the last several months on a project for Civics Day on Dec. 9, hosted by advocacy group Generation Citizen, giving students a forum to present their projects.

Now, Khan said he feels passionately about wanting to change the system because it’s something that he can relate to.

Khan’s class is an example of civics education in action. He and his classmates chose to look into the topic of testing, then read news stories and researched graduation rates at schools where students don’t have to take most Regents. They invited a city education official to brief them on standardized testing, developed advocacy tactics, and brainstormed questions to ask state education policymakers. After debating and figuring out their talking points, the students began calling and emailing members of the Board of Regents, asking them to allow more “consortium” schools, which can tie graduation to student work and projects instead of scores on Regents exams.

Their project is one example of what schools could do to give their students a richer understanding of civic participation, a state education task force believes.

Last month, the 33-member task force recommended the state adopt three changes: create a definition for civics education, allow students to earn a “seal of civic readiness,” which they can use to fulfill diploma requirements, and be able to complete a capstone project like Khan’s, which could count toward a required credit in “Participation in Government.”

Their work comes in the midst of an ongoing national conversation about the state of civics education, much of it stemming from concern about the political polarization on display after the 2016 presidential election.

In New York, state education policymakers have pointed to low voter participation and lack of basic constitutional knowledge. More than half of the nearly 23% of eligible voters who cast ballots in New York’s November 2019 thought that undocumented immigrants had no constitutional rights, according to the education department. About three-quarters of those voters could not name all three branches of government.

But much of the conversation has also turned on what must be done to ensure students can become active citizens in their communities. With that idea in mind, New York City has spent about $7.8 million on the Civics For All program over the past two years. It was launched in 2018 to provide resources, programming, and teacher training to all city schools who want to go beyond current credit requirements for social studies.

Generation Citizen, which creates teaching models that schools can use to set up action-focused civics classes, estimated it would cost $10.8 million annually to create action civics courses across the state.

The state Board of Regents largely lauded the task force’s work last month, signaling they would likely accept those recommendations, which still could be revised as the state solicits public comment on the proposals.

There’s “increased energy” around making sure students understand and know how to participate in government, said Sen. Shelley Mayer, a Yonkers Democrat, who chairs the Senate’s education committee. She sponsored a bill to encourage more high school students to register to vote, and another to create student governments in schools where they don’t exist.

“My personal experience is that students are not being taught adequately about government,” Mayer said. “They do not know, including seniors in high school — including seniors in advanced classes — what’s the difference between a state senator and a U.S. senator. We dropped the ball for a good number of years here.”

The task force is not calling for the state to require classes around capstone projects, or asking to replace any courses with it. So, the immediate impact of its recommendations, if adopted, might not be significant.

An incentive to complete a capstone project, the task force said, would be earning a seal of civic readiness, which students could use toward their Regents exam requirements. New York students must take five Regents exams to graduate, or they can take four plus take an alternate assessment, such as a three-part technical test for career and technical education programs. A seal in civic readiness would be an additional alternate pathway, if approved.

In New York City last year, just 3,743 students who graduated chose alternative pathways to graduation.

The task force decided against requiring schools add the capstone to their offerings because they did not want to create an “equity issue” if they gave schools an unfunded mandate, explained Michael Rebell, the task force’s chairman and director of Columbia University’s Center for Educational Equity at Teachers College.

“The fact is, many school districts in New York City and around the state don’t have the resources they need to support kids on a serious capstone project,” Rebell said, who helped lead the legal battle that created the state’s Foundation Aid formula, which sends extra dollars to high-needs districts. “It takes teacher mentoring, it takes teacher time, with all the state mandates, with all the things that teachers in high-need districts have to do.”

Even though the task force’s job is done for now, Rebell said he’ll continue to push for changes to civics curriculum through Democracy Ready New York, a coalition of more than 25 organizations that he’s leading. Members include the state teachers union and the League of Women Voters.

Khan’s teacher David Edelman used a teaching model from Generation Citizen to prepare his students, whose project was recognized on Civics Day with the Action Award, for using a variety of different tactics to achieve their goal.

Edelman thought that the work he’s doing at Union Square Academy could expand by having teachers like himself share notes and collaborate with other educators interested in having similar classes.

“It’s a struggle to do this, but I feel most passionate about doing this. This is why I got into teaching,” Edelman said.

Even though they’ve wrapped up the project, Edelman said some students are still calling and emailing members of the Board of Regents to advocate for their project. Some may attend one of the state’s meetings as the board starts a multi-year process rethinking the state’s diploma requirements, which could include an overhaul of Regents exams.

Even though Khan has taken his required Regents exams, and any eventual changes won’t affect him, he’s still advocating for a change. He has two younger brothers in high school who will also take Regents, not to mention, countless other students, he noted.

“It’s one of the major issues for New York state students, for high school students,” Khan said.