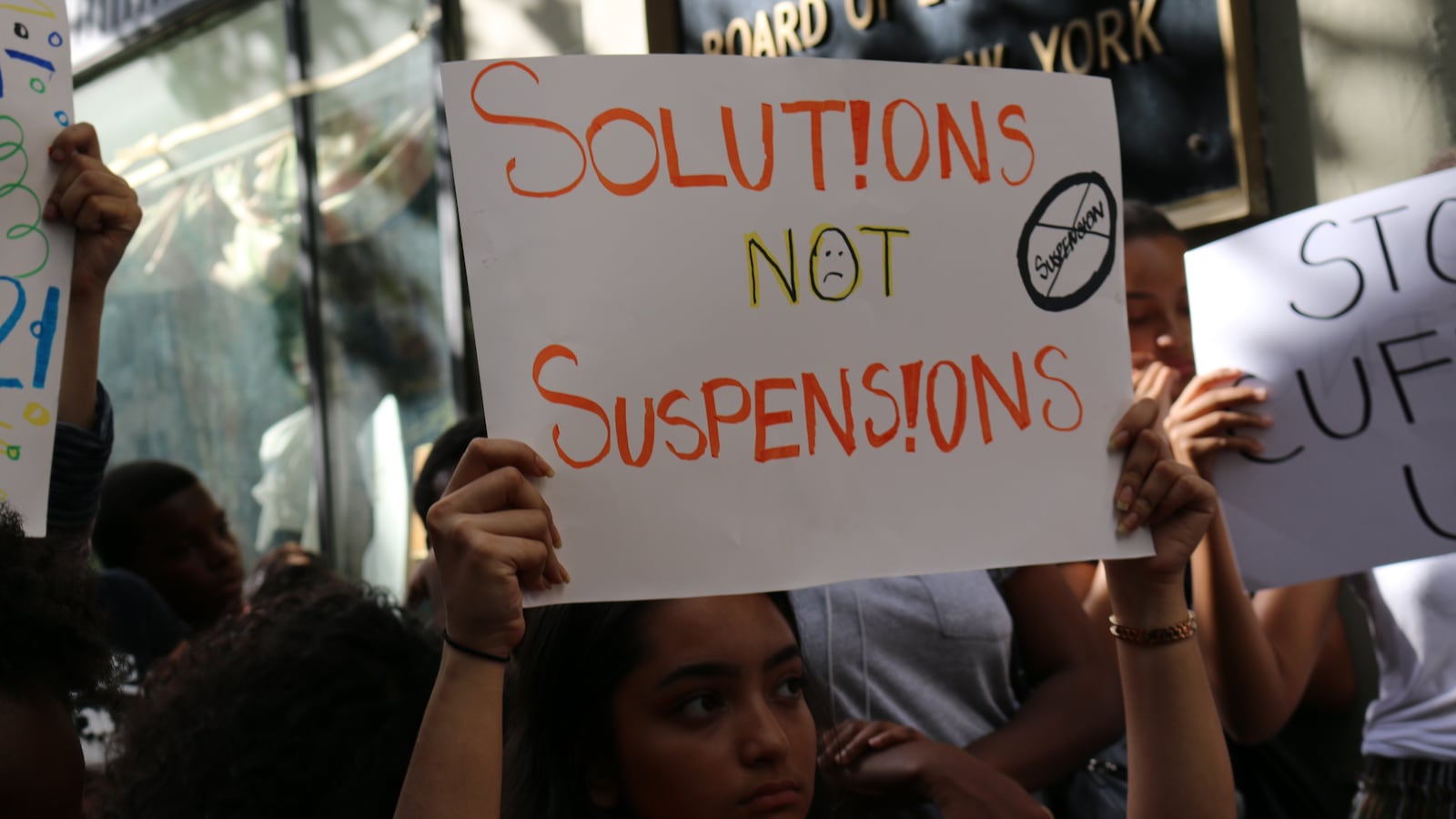

It’s a question that has roiled educators across the country: Does limiting suspensions promote student learning, or lead to more chaotic classrooms?

A new study focused on New York City middle schools adds new evidence to that contentious debate, finding that reducing suspensions for nonviolent misconduct led to across-the-board improvement in test scores and school climate.

The study, conducted by University of Michigan professor Ashley Craig and Harvard doctoral student David Martin, focused on the three years after a 2012 policy change under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg that banned suspensions for minor misbehavior such as cursing.

“The worry for a lot of people about reducing suspension rates is you potentially see students who are disruptive or dangerous stay in the classroom,” Martin said, possibly distracting from student learning. “Our paper suggests that’s not a tradeoff you face when you look at these non-violent disruptive behaviors.”

That finding offers new support for easing up on harsh responses to student misbehavior, a goal of Mayor Bill de Blasio, who has overhauled the city’s discipline code even further by limiting suspensions for other low-level infractions such as insubordination and shortening the length of suspensions for more serious infractions. Districts across the country have moved in a similar direction.

Discipline reform advocates have pushed for those changes, arguing that reducing suspensions is a civil rights issue. Students of color and those with disabilities are disproportionately removed from their classrooms, which is linked to worse academic outcomes.

Some educators have pushed back against those reforms, arguing they have made it harder to maintain order, and there has not been sufficient training in alternative approaches.

“In many schools, misconduct is on the rise, leading some students to believe there are little or no consequences for disruptive, openly defiant, and even violent behavior,” wrote Mark Cannizzaro, the head of the city’s administrators’ union, in a January letter.

The new research cuts against those concerns, but doesn’t necessarily prove that they’re misplaced, either.

The study focused on reducing low-level suspensions at a time when tough suspension policies were at their peak, and the city issued roughly 70,000 suspensions a year. It’s possible that recent policy shifts, which have since halved the number of suspensions, have swung the pendulum so far in the other direction that school climate has taken a hit.

“Subsequent reforms that are targeting more serious infractions — it’s not obvious that you’d expect the same effects,” Martin said. “You might see more of a tradeoff.”

The study focused on the elimination of “level two” infractions, non-violent behavior that included cursing and “persistent non-compliance.” Suspensions for this type of behavior were already fairly rare, but some schools used them more than others.

The researchers took advantage of the considerable variation in suspension rates between schools. Those that issued more level two suspensions — and were suddenly banned from issuing them — were compared to schools that barely issued any, creating a de facto control group that allowed the researchers to isolate the effect of reducing suspensions.

The study, which has not been formally peer-reviewed, found that reducing suspensions caused the average student at a high-suspension school to improve their math scores by about one percentile and boost reading scores by half a percentile in the three years after the policy change — a positive albeit modest shift. A broad range of students seemed to benefit, not just those most likely to be suspended.

At the same time, reports of disruptive incidents fell, and students and educators reported improvements in school culture, according to teacher and student surveys.

“These correlations are consistent with school culture being an important driver of the test score gains from the reform,” the authors wrote.

It’s hard to disentangle the effect of reducing suspensions by itself with the effect of encouraging schools to move toward alternative approaches to student misbehavior. Advocates of discipline reform have long argued that schools should do both.

The 2012 policy shift pushed schools to remove students from class for a single class or use alternative “restorative” practices, such as peer mediation. But the study did not offer a detailed account of what strategies, if any, schools were using in lieu of suspensions.

Matthew Steinberg, a George Mason University professor who has studied school discipline, said the study was rigorous and added to the small but growing literature on the effect of suspensions. He was skeptical of the idea that eliminating suspensions alone explained the improvements.

“What was happening as an alternative to suspension?” Steinberg asked. “That is a critically important question.”

Although other school systems have scaled back suspensions and adopted alternatives to exclusionary discipline such as restorative justice, there is little conclusive research about its effect on student outcomes.

One study, based on a restorative justice initiative in Pittsburgh, found that the approach reduced suspension rates and improved teachers’ perceptions of school climate, but also led to lower test scores, particularly among black students.

Another recent study, which looked at an unnamed California school district, found that suspensions were linked to slightly higher math scores among students who were not suspended. That suggests that reducing suspensions without putting in place effective alternatives could backfire.

Meanwhile, big questions remain in New York City about how the dramatic reductions in suspensions from more exclusionary policies are affecting students — and Martin said more research is needed to answer that question.

“The rate at which we’re reversing those policies is in some ways outpacing the rigorous evidence that we do have,” Martin said.