More than one million New York City students are slated to begin remote learning next week, but the education department acknowledged Thursday that it could take weeks before all students have the technology they need to communicate with their teachers.

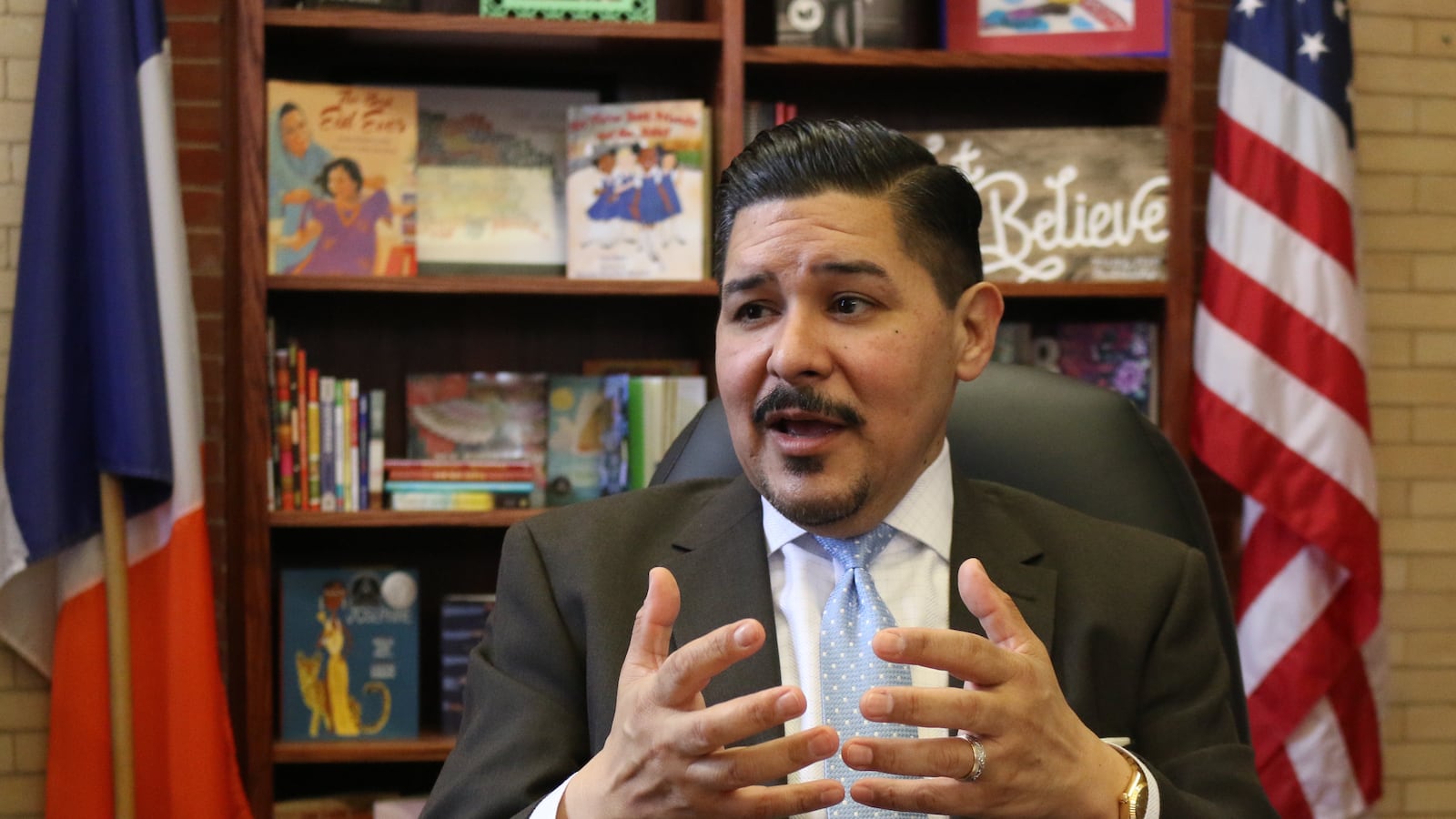

“We’re not going to have 300,000 devices by Monday — we never said we would,” said Chancellor Richard Carranza, referring to the city’s estimate of the number of families who need technology to work remotely. “We do have a plan for having those devices in the hands of our students in the coming weeks.”

The city is prioritizing devices for students who live in public housing, come from low-income families, or are homeless and anticipated distributing 25,000 devices over the next week, Carranza said. Some schools are also distributing materials on paper.

But that still means thousands of students will not be able to fully connect with their schools or teachers for lessons immediately, an indication that the transition to online learning will be bumpy.

Aide Zainos went to her children’s elementary school in the Bronx today in the hopes of securing devices for her second and fourth grader. But she said they didn’t have enough to lend, since they were prioritizing students in shelters and others with greater needs. She said she understood.

“If they are really in need, don’t worry, give it to them,” Zainos said in Spanish.

Zainos hopes to borrow a computer from her husband’s coworker so that their two children can get online. Worse comes to worst, she’ll resort to using her phone.

“It’s not the same, but I said, ‘It doesn’t matter. We’re going to adapt to the little that we have,’” she said. “It’s nobody’s fault.”

Zainos is the Community Education Council president for District 9 in the Bronx, but she has still found it difficult to understand how the shift to online learning will happen. She still hasn’t received the needed code to make online accounts for her children, and said the education department needs to do a better job communicating with parents.

“They haven’t explained how this work is going to happen,” she said. “We need a better explanation.”

Parents and advocates said they’re worried that unequal access to technology could put some students at an even greater disadvantage.

“It’s definitely going to show the haves and the have nots,” said NeQuan McLean, a parent council leader in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

He said some students in his district have been receiving laptops that have been used at their schools, and said his district appears to have enough technology on hand. Still, school computers depend on families’ access to the internet, potentially limiting their utility, McLean added.

That’s the challenge facing Brigitte Bermudez, whose 11-year-old daughter picked up a laptop from Mott Hall Science and Technology Academy in the Bronx. The family does not have internet at home, so her daughter’s teacher told them that Spectrum was offering free service for K-12 students affected by recent school closures. (You must sign up as a customer and will be billed after 60 days).

But when Bermudez called, a representative told her that Spectrum didn’t offer service in her area and suggested she call Optimum, which is offering a similar service. When she called Optimum, a representative told her she still owed $150 from an unpaid cable bill from a few years ago and wouldn’t be able to set up the account.

Bermudez said she isn’t working right now and can’t pay the bill. A neighbor has offered the family her WiFi password. But Bermudez said that when it works at all, it can be slow, “so it comes out to be a lot of difficulties.”

Bermudez’s problem is not rare, said parent Tom Sheppard, who sits on District 11’s parent council in the Bronx. He’s heard from other families with the same issue, and worries that families don’t have enough information about how to best access the devices they’re getting.

Sheppard, who worked for a decade as an Apple technician, said he’s worried about how parents will troubleshoot problems if the devices act up, noting that one school in his district handed out 5-year-old iPad minis that were shelved until this week. Will it be up to the schools to help, or will parents have a phone number to call, he wondered.

“The best analogy I can give is watching a slow-motion trainwreck,” Sheppard said. “People are doing the best they can under the circumstances, so I don’t want to sound like I’m going in on the DOE, but I believe in my heart they were wholly unprepared for this.”

Another massive challenge of ramping up online learning: figuring out who needs technology in the first place. Department officials recently began asking families to tell them if they don’t have access to technology so they could give them internet-connected iPads, and have since extended pick-up into next week.

Schools were supposed to distribute surveys, but efforts to reach families have proved complicated. Some advocates said they worry parents won’t fill out the survey and that schools may struggle to reach them. The survey was only originally available in English, but by Thursday it was available in nine languages.

Families who could not access the survey were also asked to call 718-935-5100 to report what they needed. Department officials also planned to tell families how to access the survey at sites where they could pick up grab-and-go meals.

“This is an ever-changing situation and schools will be communicating additional guidance and directions for pick-up of laptops, tablets, and printed materials with their communities in the coming days,” education department spokesperson Danielle Filson said in a statement. “We continue to urge all families who are requesting a device to fill out the remote learning device survey.”