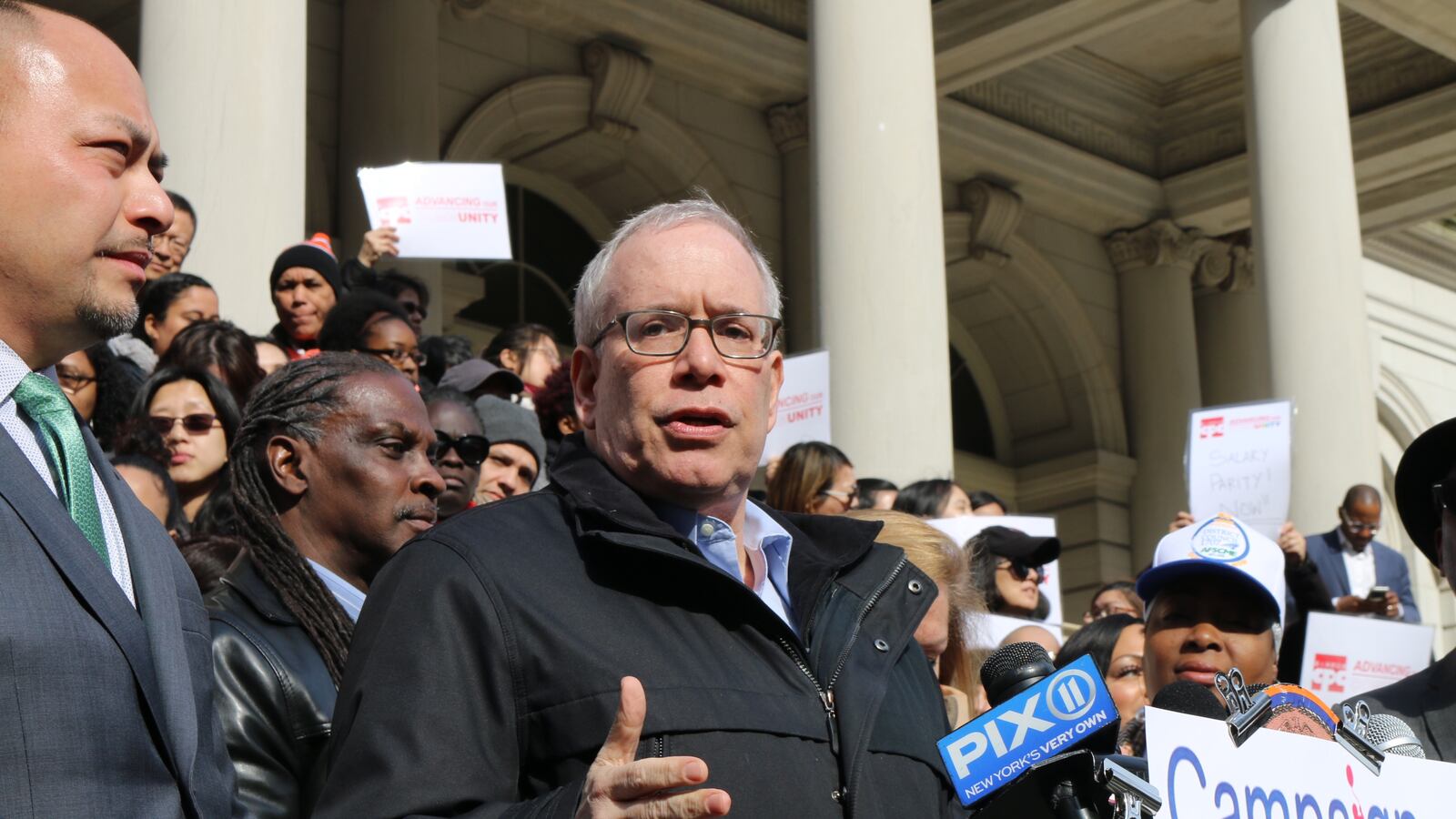

Homeless students should be allowed to attend the city’s under-enrolled child care centers, set up for families of frontline workers responding to the coronavirus pandemic, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer said Wednesday.

Echoing calls from advocates, Stringer asked Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza to open these centers up to homeless students, charging that shelters are not an appropriate place for students to learn. Students in shelters often don’t have the space and supports needed for remote learning, like internet access.

“For students who are homeless, the stability and continuity of a safe learning environment could make the difference between keeping pace and falling behind their peers,” Stringer wrote in a letter to Carranza. “We simply cannot afford the devastating consequences for these children if they fall further behind.”

Just a week after the city closed schools because of the coronavirus, it opened 93 “regional enrichment centers” where workers in healthcare, transit, and emergency services could send their children. The idea was to ease the burden of school closures on some of the city’s most critical workers.

But enrollment in the centers and attendance has remained low, leading the city to open the centers up to children of workers in grocery stores, pharmacies, and a few other city agencies.

Last week, low enrollment led the city to close 23 of these centers, in part to allow school nurses to help with other healthcare needs as the city braces for critical weeks of its coronavirus response.

City officials have emphasized that the centers are to ensure that essential workers aren’t burdened with child care and unable to come into work.

“That’s really the crucial crux of this matter — is making sure we are supporting these essential workers and giving them those options in terms of their kids,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said last week.

But given the low enrollment, advocates have urged the city to add homeless students to the remote learning centers. Council Speaker Corey Johnson and Brooklyn Councilmember Stephen Levin called for the same.

“As we rise to meet the challenges of remote learning during this time of crisis, we must do all we can for our most vulnerable students,” Johnson and Levin said in a joint statement on Wednesday, following Stringer’s letter.

City officials said Wednesday they had delivered internet-connected iPads to the 12,000 students in city shelters. Even if students are able to get a device from their school for remote learning, they often lack access to the internet in their shelters.

That’s what happened to 10-year-old Allia Phillips, who is in a shelter on the Upper West Side.

“I went downstairs to find out that they don’t have any internet,” Kasha Phillips-Lewis, Allia’s mother, told the New York Times. “You’re screwing up my daughter’s education. You want to screw me up? Fine. But not my daughter’s education.”

Allia has since received an iPad, officials said.

Read the full letter below: