A week after Mayor Jim Strickland largely dismissed a new coalition’s call for a $10 million investment in education, the group is taking its message to Memphis billboards.

Fund Students First — comprised of elected officials, education advocates and public school leaders — posted two billboards Friday in high-trafficked streets in downtown and midtown Memphis. The campaign is being underwritten by Stand for Children, a national education advocacy group with offices in Memphis and Nashville.

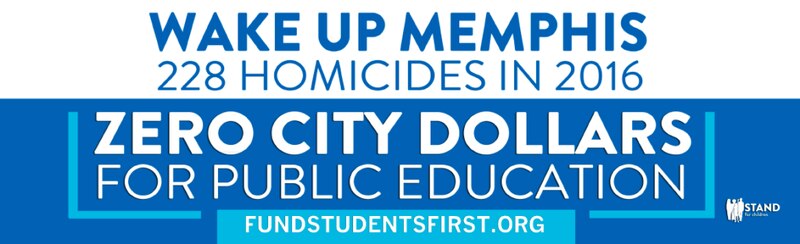

One of the billboards reads:

The message plays off a controversial billboard campaign launched earlier this year by the local police union in an attempt to tie the city’s high murder rate to vacancies in the police department. Under Strickland’s proposed budget for next year, that department would receive a significant boost.

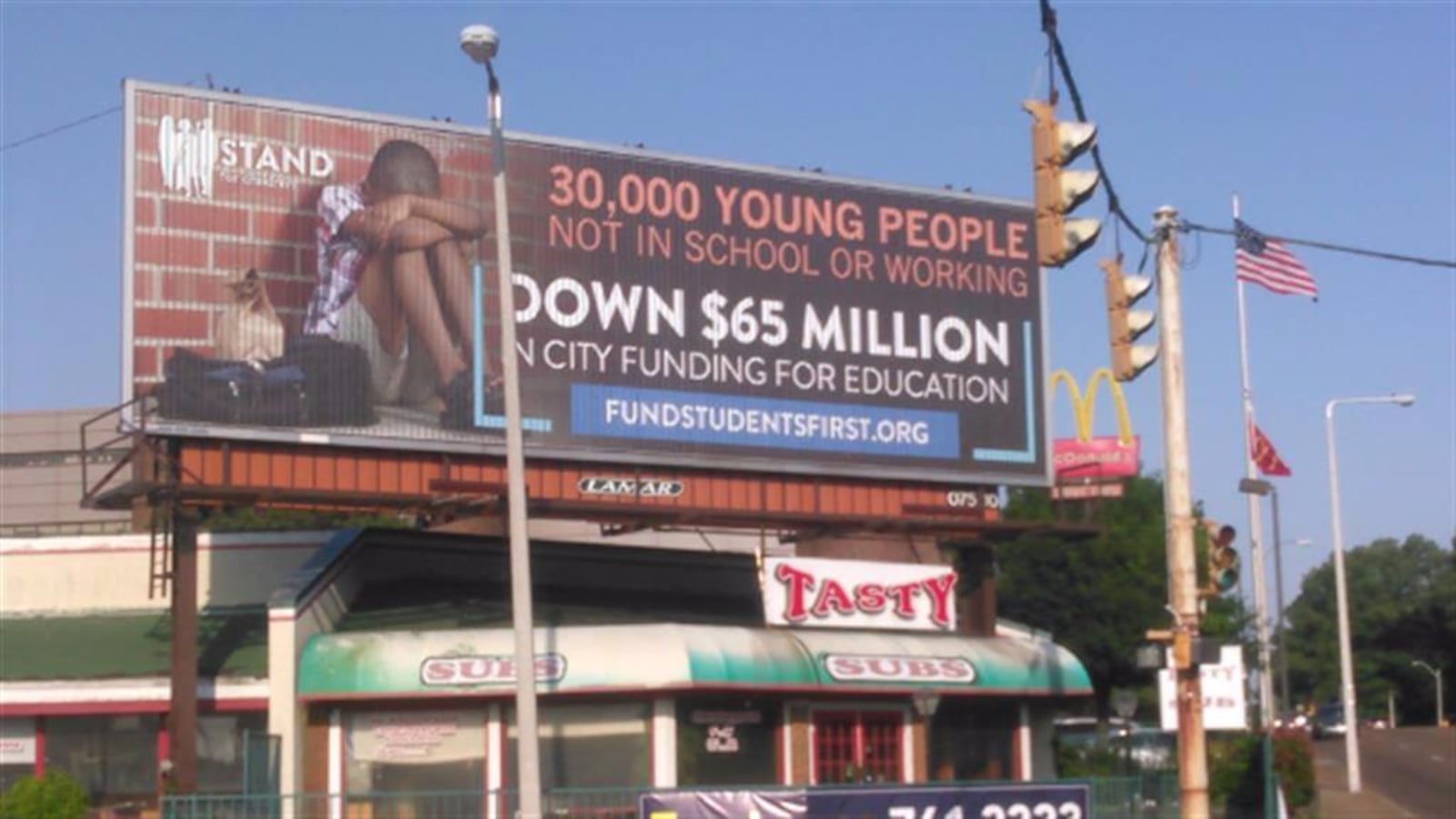

The other billboard says:

That message alludes to the mayor’s call for more job training for youth and young adults, even as the city has refused to set aside money that could be tapped by public schools.

The education campaign highlights frustration over years of tenuous funding for Memphis schools, but especially since the city school system voted to give up its charter in 2010 and merged with the suburban Shelby County Schools in 2013. County government is now the sole funding agent for consolidated Shelby County Schools, which last year prompted County Commissioner Terry Roland to refer to city government as a “deadbeat parent.”

Just before the consolidation, the city contributed $65 million annually to Memphis schools, which was about 5 percent of the district’s revenue. Next year’s budget for Shelby County Schools is $985 million.

This spring, education groups that often are at odds with each other formed the Fund Students First coalition, asking Strickland to put his money where his mouth is.

Elected in 2015, Strickland campaigned to make Memphis “brilliant at the basics” — a slogan that coalition members say should include public education.

“That should be a ‘basic’ of what we should have to do to move our city forward,” said Cardell Orrin, Stand for Children’s Memphis director.

Presenting his $680 million spending plan this week to City Council, Strickland mentioned youth first. He said his budget would restore Friday hours to libraries and expand teen programming, as well as maintain a summer job program for 1,400 students and add a literacy component for summer camps.

“First, and most importantly, the future of our city is only as strong as our young people,” Strickland said. “…Yet we know the No. 1 job of city government is to provide for public safety.”

The coalition has called for a direct city investment of at least $10 million to help pay for career and technical training for in-demand jobs, as well as after-school programs and social supports for potential dropouts. The group wants at least half of the money to be funneled through public schools and the rest through community programs.

Strickland has said the city faces “serious and well-documented budget challenges” due to the gradual elimination of the state’s Hall income tax and required increases in the city’s pension fund. He added that Memphis taxpayers decided in a 2011 referendum that they did not want to be “double-taxed” by putting in money to education through both city and county coffers.

But Tomeka Hart, a former city schools board member and one of the architects of the merger, questioned Strickland’s framing.

“(Double-taxation) had nothing to do with the reason behind the merger,” she said. “They could fund the school system if they want to.”

Hart said the referendum was about protecting school funding from impending state legislation that would have allowed the county school system to wall off its funding in a “special school district,” similar to the current municipal school districts that ring the city. She said the double-taxation argument came up when City Council members wanted to cut school funding in 2008.

Strickland served on City Council at that time and was one of the original proponents of a $66 million cut to city funding for legacy Memphis City Schools. That cut sparked a lawsuit and a settlement that has the city still paying $1.3 million annually to Shelby County Schools. Last year, school and county officials chided the city government for paying nothing more.

The coalition has proposed that the city invest $10 million in a fund that would be managed by a nonprofit organization. That would prevent the city from being locked into giving that amount every year as mandated under a state law known as “maintenance of effort.”