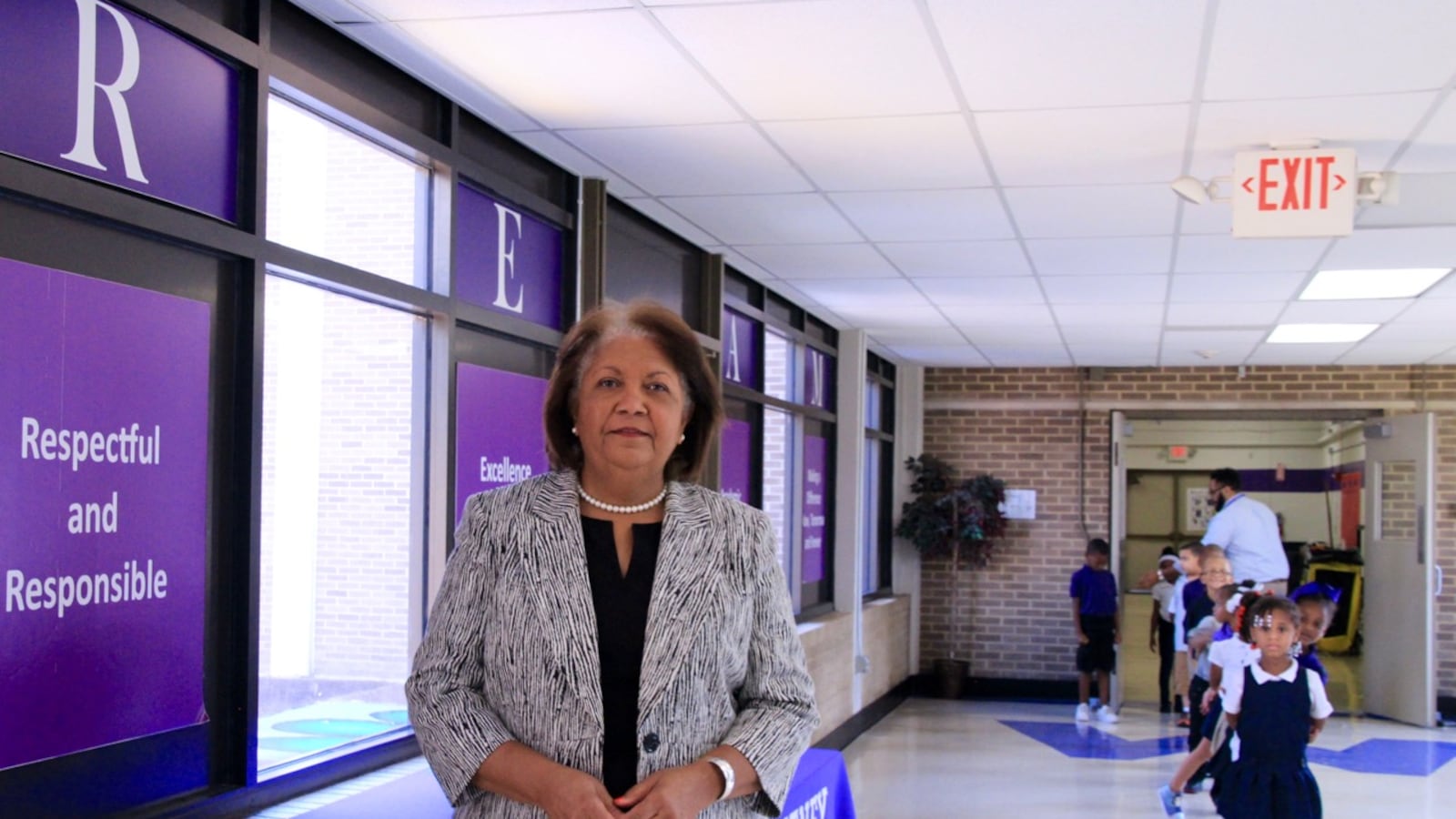

As the newly named chief academic officer for Tennessee’s turnaround district, Verna Ruffin said one of her first priorities will be investing in their top tier teachers.

“We know that we have critical work to do,” Ruffin said. “And we also know that investing in our classrooms is a sure way to move the needle on student achievement. We have teachers who are doing amazing work. We need to amplify them.”

Ruffin joins the state’s Achievement School District, known as the ASD, during a chaotic season of change. One month after she was hired as part of a major leadership team overhaul, the district’s superintendent, Malika Anderson, announced she was stepping down. Ruffin will work with the interim superintendent, Kathleen Airhart, until Anderson’s replacement is hired.

When the state-run district launched in 2011, it was with the aspiration to turn around schools performing in the bottom 5 percent of the state through new charter management. But results have lagged, and school leaders say turnaround work has been harder than expected in Memphis, where many of their students live in generational poverty and come to school behind grade level.

Ruffin’s role with the five-year-old district is a new one. She will oversee the district’s five direct-run schools in Memphis called Achievement Schools, a role previously filled by the former executive director, Tim Ware. But her job description also includes raising the academic bar across all 32 ASD schools and promoting more collaboration among them.

The most recent round of state test scores show the district has work ahead to reach its visionaries’ original goal. The state’s growth scores, announced last week, rank the Achievement district as a level 1, the lowest possible score. And within the direct-run Achievement Schools, which Ruffin directly oversees, three of five schools scored a level 1.

Ruffin got her start in education more than 30 years ago as a band director in Louisiana before moving into school leadership roles. She was an assistant superintendent in Tulsa, Okla., where she specialized in working with low-performing schools, before becoming superintendent at Jackson-Madison County Schools in 2013. She will earn $115,000 a year with the Achievement Schools.

We sat down with Ruffin to hear about her game plan for improving the Achievement district’s academics in her new role. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for brevity and clarity.

Tennessee’s growth formula, known as TVAAS, ranked the ASD as a level 1 overall for academic growth. What is your initial read of those scores, and how do you plan to raise the bar?

I’m very proud of the schools that earned a rating of 5 and for their contributions for growing students beyond a typical year’s growth. Of the five schools in the direct-run Achievement Schools, we had one at a level 5 and one at a level 3.

But the other direct-run schools and a number of schools within the whole network received a level 1. There is an urgency to focus on instruction and strategies to help children become successful. I’m thinking through — what does this mean for individual schools?

A focus for me will be to look at staff members and their individual TVAAS scores. We have level 5 teachers, and we can get them to collaborate more and bring their strengths to their own campuses, but also to the ASD as a network. The TVAAS conversation is still challenging to understand. How do you measure growth? How can you determine that when the assessment has changed? It can be hard to get people to subscribe to something you can’t explain, and we’re having ongoing conversations about what the data can tell us moving forward.

Talk to me more about your vision for investing in individual teachers to raise academic performance.

When I was superintendent in Jackson-Madison, we added instructional times in the afternoons at one of our lower performing schools. We sought level 4 and 5 teachers across the district and asked them: “Would you come teach at this school in the afternoons during their after-school program?” We asked the teachers to look at the data of students within that school and come up with a plan for what they were going to teach the children. We opened up an application process, and teachers came. That year, this school jumped from a level 1 to a level 5 in growth. We attribute that to the emphasis on instruction and the quality staff that was willing to work with the children in an after-school, purposeful, instructional model.

We think that this model, effectively implemented, is how you’re going to change learning for children. We do not have enough level 4 or 5 teachers across the district to just say, we’re going to take a level 5 teacher from this school and put them over in this school because then we’re going to create a deficit model. So, it’s about how to utilize the talent of your current staff and spread it out so they can influence children in another school in an acceptable way to teachers. This is something I would absolutely consider doing within the ASD.

What do you see as the biggest challenge for the ASD as a whole?

I think one of the biggest challenges is that the ASD has existed with a tremendous amount of autonomy, and people are accustomed to that autonomy. And they may not quite embrace the fact that even if we have autonomy, we have a shared goal. And we have to meet that goal.

So, the autonomy of the ASD isn’t going away, but we have to better describe and define what an ASD education is. Our goal is the same for every school in the ASD, to raise student achievement. We have a moral responsibility working with the bottom 5 percent in the state of Tennessee to not stay at the bottom 5 percent. And so, having said that, there are some things that we’ve got to do that are non-negotiable that will get us out of the bottom 5 percent of schools. We have to be better. We have to figure out what’s going to make the ASD stand out, and how we work together as a very diverse group of schools.

Part of your role is to foster more collaboration between the direct-run Achievement Schools and the other charter-run schools within the ASD. What is your vision for building cross-district collaboration?

First, is taking the time to make connections. We are doing this work together, and the only way we can do that is to know one another. It’s a very small, but a big step. I am planning on meeting with the other chief academic officers in the ASD to work in step with them on a vision for the future.

We’re also creating a new academic team, which we are still in the process of hiring for. This team will include content specialists in literacy and math that will work across the district. These specialists can help us zero in across the district on what effective instruction is.

Our focus — across all ASD schools — on kindergarten through third-grade literacy is also going to be very strong this year. I’m asking questions like, “What does a phonics lesson look like across the ASD? How can we learn from one another on how to better teach phonics?”

We’re no longer working in silos, but there’s going to be collaboration on what classroom instruction looks like. And then we’re going to better monitor that instruction and hold ourselves accountable to making the gains we have to make.