A national pioneer in school turnaround work, Tennessee this month received a report card of sorts from researchers who have closely followed its two primary initiatives for five years.

The assessment was both grim and promising — and punctuated with lessons that already are informing the state’s efforts to improve struggling schools.

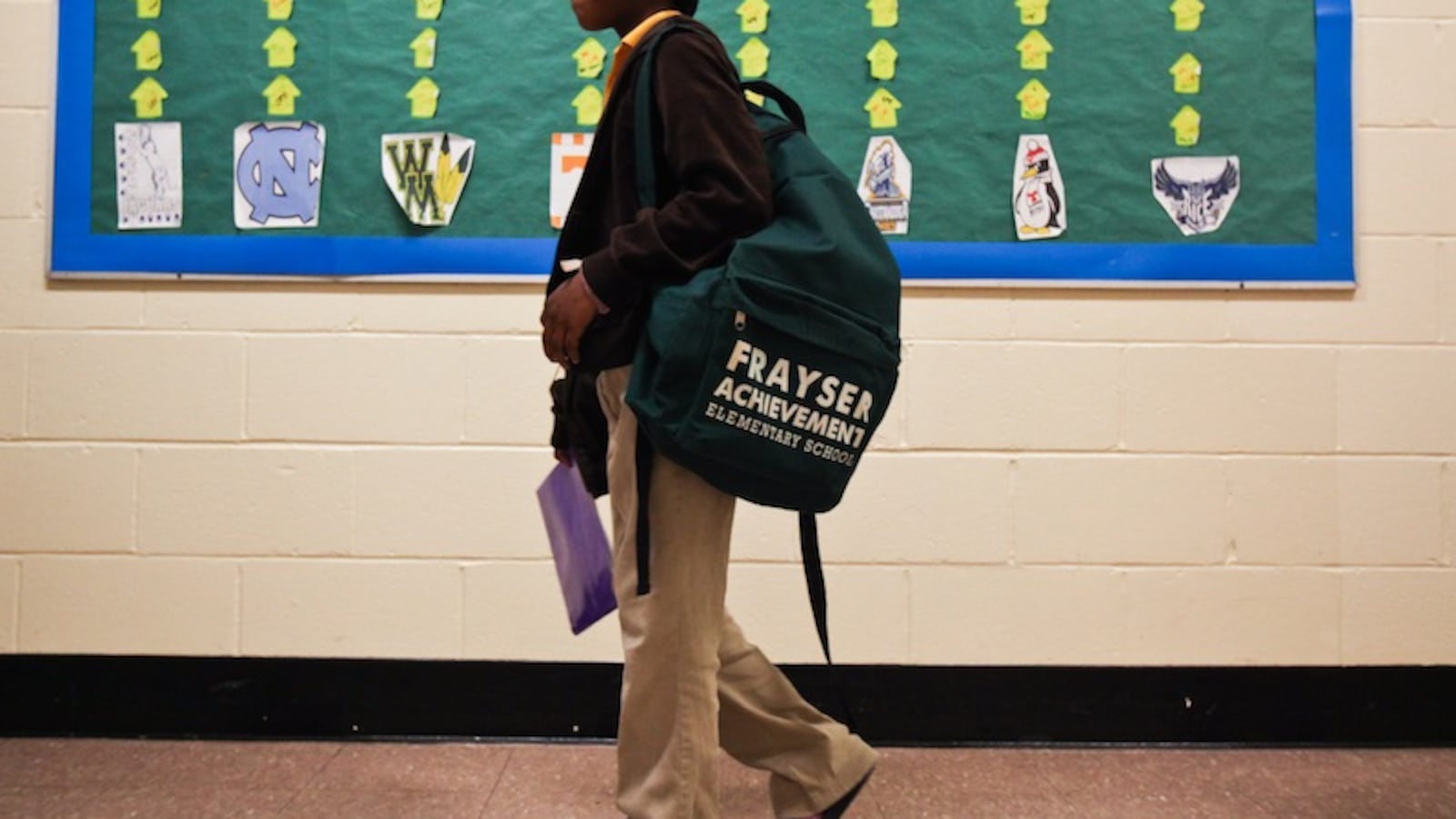

The grim: The state-run Achievement School District fell woefully short of its initial goal of vaulting the state’s 5 percent of lowest-achieving schools to the top 25 percent within five years. This model, based on the Recovery School District in Louisiana, allowed Tennessee to take control of struggling local schools and to partner with charter management organizations to turn them around. But not only has the ASD failed to move the needle on student achievement, it has struggled to retain teachers and to build a climate of collaboration among its schools, which now number 32.

The promising: Innovation zones, which are run by several local districts with the help of extra state funding, have shown promise in improving student performance, based on a widely cited 2015 study by Vanderbilt University. The model gives schools autonomy over financial, programmatic and staffing decisions, similar to charter schools. While iZones exist in Memphis, Nashville and Chattanooga, the most notable work has been through Shelby County Schools, now with 23 Memphis schools in its turnaround program. Not only have student outcomes improved in the iZone, its schools have enjoyed lower teacher turnover rates and greater retention of high-quality teachers.

One big lesson, according to this month’s report: Removing schools from their structures of local government isn’t necessary to improve student outcomes.

That explains Tennessee’s decision, under the new federal education law, to include partnership zones as part of its expanded turnaround toolkit. The model offers charter-like autonomy but is governed jointly by local and state officials. The first zone will launch next fall in Chattanooga, where the school board reluctantly approved the arrangement recently for five chronically underperforming schools that otherwise would have been taken over by the ASD.

The partnership model avoids the toll of school takeover, which the report’s researchers say contributed to community mistrust of the ASD, especially in its home base of Memphis.

“That faith in the ask of these schools going to the state operator came with the promise to raise student achievement,” said researcher James Guthrie. “To not see this achievement in the first round of results raises a crisis of legitimacy (for the ASD).”

Guthrie is among researchers who have followed school turnaround efforts as part of the Tennessee Education Research Alliance, or TERA. The group’s work continues to guide the State Department of Education on what has worked, what has not, and why. Education Commissioner Candice McQueen requested their five-year summary as part of the state’s own self-analysis, as well as to inform school improvement work nationwide.

In interviews with Chalkbeat, TERA researchers emphasized that the final word hasn’t been written on any of the turnaround models in play in Tennessee. They continue to track students in struggling schools. And they emphasized that turnaround is a long game, one that the ASD’s founders underestimated.

“The cautionary tale of any reform is to be realistic about what you can achieve,” said Ron Zimmer of the University of Kentucky. “…If (the ASD) had been more realistic, people would have had more realistic expectations (about) what would have been deemed a success.”

The operators of ASD schools have had a steep learning curve amid daunting challenges that include high student mobility, extreme poverty, a lack of shared resources, barriers to school choice, and on-the-ground opposition.

Five years in, there’s still hope that the ASD can improve its schools with more time, said Joshua Glazer of George Washington University.

“We have seen that several providers have learned some hard lessons and are now applying those lessons to their models,” Glazer said. “Many have overhauled curriculum and taken a very different approach to supporting teachers. Across the board, providers have realized that much more robust systems of guidance and support are needed. These changes have the potential to lead to better student outcomes, but only time will tell if scores will go up.”

The state recently recruited a new academic leader, and it’s looking for a new superintendent who can create a more collaborative environment within the ASD’s portfolio of operators and schools. The district also underwent a major restructuring over the summer, cutting staff to curb costs and streamline roles as federal money ran out from Tennessee’s Race to the Top award.

Funding will be among the biggest long-term challenges for both the state-run district and the local iZones, said Zimmer.

While the Memphis’ iZone has shown initial success, it’s an expensive model that includes educator bonuses and adds an hour to the school day.

The ASD also needs adequate funding, but Zimmer said that became harder when its schools did not produce early gains. “It takes up to five or six years before see we significant benefit from a program like the ASD,” he said. “The problem is that people don’t have the political patience to wait for it.”

McQueen emphasizes frequently that all of the state’s turnaround models work together. She and Gov. Bill Haslam remain steadfast in their support of the ASD — a point she drove home again on Wednesday when asked about the embattled district.

“It is the state’s most rigorous intervention as noted in Tennessee’s recently approved ESSA plan,” McQueen said, “and is clearly a critical part of the state’s accountability model.”

For more discussion about the five-year brief, you can read blog posts in Education Week from TERA and the State Department of Education.