In her first official stop in Tennessee as secretary of education, Betsy DeVos praised career and technical education at a traditional public school, but also put in a good word for vouchers in a state that has consistently eschewed them.

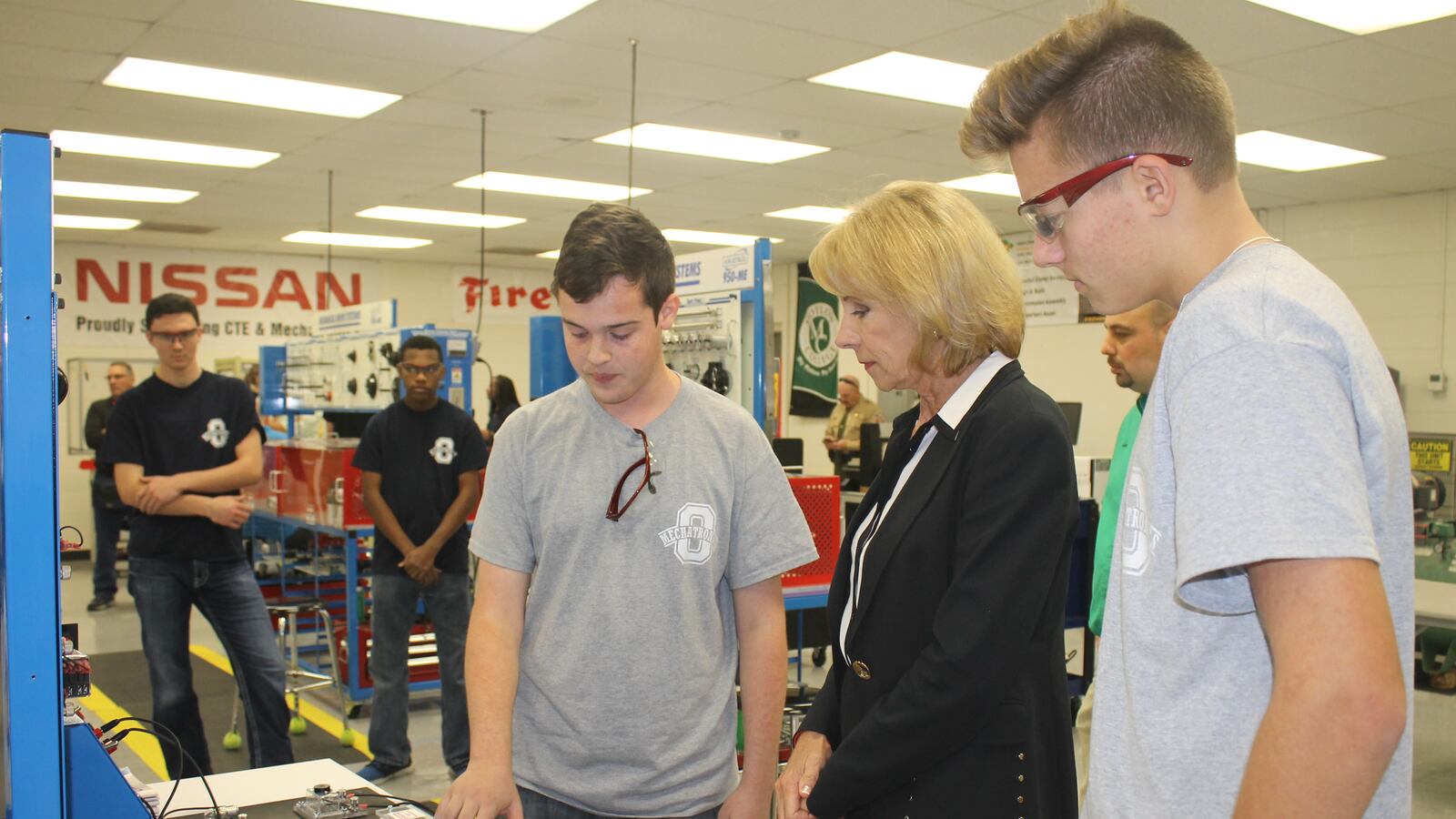

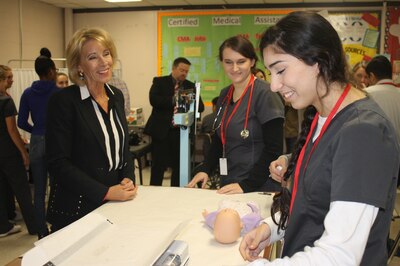

DeVos visited Oakland High School in Murfreesboro, a fast-growing university town south of Nashville, and spoke with students taking classes in health sciences, automotive technology and mechatronics.

She lauded the school for “addressing individual students’ needs and aptitudes and helping them to prepare for their adulthood very early on” — in partnership with regional industries that are heavy on healthcare and automobile production.

But even as she praised instruction happening at Oakland, DeVos encouraged Tennessee lawmakers to approve a voucher program. Vouchers would allow parents to use public funding to send their children to private schools, despite recent studies showing that student achievement dropped, at least initially, for students making that leap in Louisiana, Indiana, Ohio and Washington, D.C.

“I think empowering parents to make the right decision for their children is important, no matter what state and no matter what community,” she told reporters when asked about Tennessee’s perennial tug-of-war over vouchers. “We have far too many students today that are stuck in schools that are not working for them and parents that don’t have the opportunity to make a different decision.”

Since becoming the nation’s education chief in February under President Donald Trump, DeVos has been tasked mainly with overseeing the new federal education law that shifts most decision-making back to states. With her diminished authority, she is using her position as a bully pulpit to promote policies that she favors, including expanding school choices for families. She is a big proponent of charter and virtual schools and using vouchers or tax credits to go to private or church-run schools.

While Tennessee has more than a hundred charter schools and a few virtual schools, its legislature has consistently shied away from vouchers. Lawmakers will take up the matter again in January with a proposal that would pilot a program in Memphis, home to a large concentration of low-performing schools that local and state initiatives are attempting to turn around.

At least one longtime voucher proponent told Chalkbeat that the prognosis isn’t good for passage in 2018 in the House of Representatives, where the proposals have stalled each year.

“I would hope that the politicians would put the kids first, but kids don’t vote. Public school employees do, so I’m not as optimistic,” said Rep. Bill Dunn, a Knoxville Republican who has sponsored voucher legislation in the past.

One reason might be districts like Rutherford County Schools, where DeVos visited on Wednesday. Last spring, school board members there urged their representatives to oppose vouchers through a resolution that says vouchers “hurt the free public education system, divert limited state education dollars to private interests, and have been shown to hurt the academic progress of students.”

DeVos came to Tennessee in conjunction with the National Summit on Education Reform, which kicks off on Thursday in Nashville. The annual event is hosted by her friend Jeb Bush, the former governor of Florida. DeVos will deliver a keynote address.

About 1,100 education leaders and influencers from across the nation are scheduled to attend the summit and — as has happened frequently when DeVos comes to a city — several teachers unions are planning a protest against what they call her “anti-public education agenda.” DeVos was among the most controversial picks for Trump’s cabinet, in part because the Michigan billionaire came to the job with little experience with public schools.

At Oakland High School, the faculty, students and administrators who showed DeVos around said they hoped she came away from their campus with a greater appreciation for what goes on there.

“We’re public education, and we do it right,” said principal Bill Spurlock.

Brianna Bivins, a junior, added that she doubts a private school could offer the health sciences classes that she takes at Oakland. “It’s good for her to see this kind of class,” she said of DeVos. “It gives a good perspective of our public schools.”