On paper, one student’s suspension from Kirby High School was routine. She had told her teacher to “shut up!” after the teacher made multiple attempts to stop her from talking during the day’s lesson. There had to be a consequence.

But in a meeting later, behavior specialist Clarence Shaw sought to understand the “why” behind the student’s misbehavior.

“What was going on right before you told him to shut up?” he asked the student.

“He’s got a short temper, just like I do,” she answered. “And I started saying one thing and he started getting loud. And I told him to shut up and he put me out of his class.”

The teen continued: “He wasn’t telling anyone else to be quiet. He kept calling my name out.”

That’s when Inger Spikner, another behavior specialist for the 900-student Memphis school, chimed in — and then helped to reframe the incident.

“You feel like you’re being singled out,” said Spikner, a former teacher. “When in actuality, you are because as a teacher I’ve identified you as a leader and I know if I can get you to be quiet, then everybody else will follow suit. So when a teacher singles you out going forward, I need you to know that there’s this kind of, like, an unwritten or unspoken code. You’re a leader and you don’t even realize your status.”

By the end of the 10-minute conversation, Spikner and Shaw had identified what triggered the student’s behavior, helped her think through the consequences of her words, and planned to follow up with the teacher to make sure a suspension was truly the last resort.

Shaw and Spikner are among 19 behavior specialists hired this year by Shelby County Schools to serve nearly all of its 145 schools. By giving students individual attention, they seek to pinpoint the root cause of misbehavior and then work with those students to make better choices. The goal is to help avoid school suspensions, as well as to acclimate suspended students back to school.

And it’s working. Two years ago at Kirby, the administration suspended students 333 times in the first 80 days of school. This school year, the number of suspensions during the same time period was cut in half. And the number of in-school suspensions has gone from 346 to just 47 this year.

That’s especially important because the Memphis district has the highest rate of suspensions in Tennessee, significantly contributing to racial disparity when it comes to how students are disciplined across the state. Statewide data from 2014-15 shows that Tennessee students were more likely to be suspended if they were black boys or live in Memphis. And if students aren’t in school, they’re more likely to fall behind in their schoolwork and get frustrated, creating more behavior problems.

Steevon Hunter, Kirby’s first-year principal, said behavior specialists are a welcome new resource at his school.

“When I get together with my administration team each week, one of things on our agenda is our frequent flyers … particularly with behavior. And we’ve seen those frequent flyers decrease (with the help of behavior specialists),” said Hunter.

“It’s one thing to suspend a kid,” he noted, “but it’s another to get to the ‘why.’”

Behavior specialists are not new to Memphis schools. Memphis City Schools had them, but the department was cut when city and county schools merged in 2013. Then last year, the consolidated Shelby County Schools hired Michael Spearman, who is also a longtime detective for the Memphis Police Department, and Ron Davis, a former behavior specialist under Memphis City Schools, to go into 30 schools as a pilot program. They reduced suspensions by 5 percent, convincing Superintendent Dorsey Hopson to invest $1.5 million to hire more behavioral specialists to serve the entire district.

Next year, the plan is to add even more.

Behavior specialists are different from counselors because they don’t have power to recommend or impose punishment. They visit weekly with students and also meet with teachers and principals to develop behavioral improvement strategies.

“You can have an impact on kids one-on-one,” Spikner said.

“We’re not so punitive,” adds Shaw. “We create that safe space. Once they open up, then we can focus on changing their behavior.”

Memphis schools haven’t used corporal punishment for more than a decade, but have been slow to provide alternative disciplinary measures. Meanwhile, there’s increasing recognition of the need to help students who are dealing with personal trauma, which sometimes can lead to behavioral problems. Behavior specialists are helping to bridge the gap, according to Roderick Richmond, who oversees the district’s student support services.

“I think that everyone throughout the community is realizing the importance of being able to provide social and emotional support for students,” he said. “We’re seeing some of the trauma that our students are experiencing — both students and parents — and when they’re experiencing some of that trauma, how we address that in the school buildings is very, very important.”

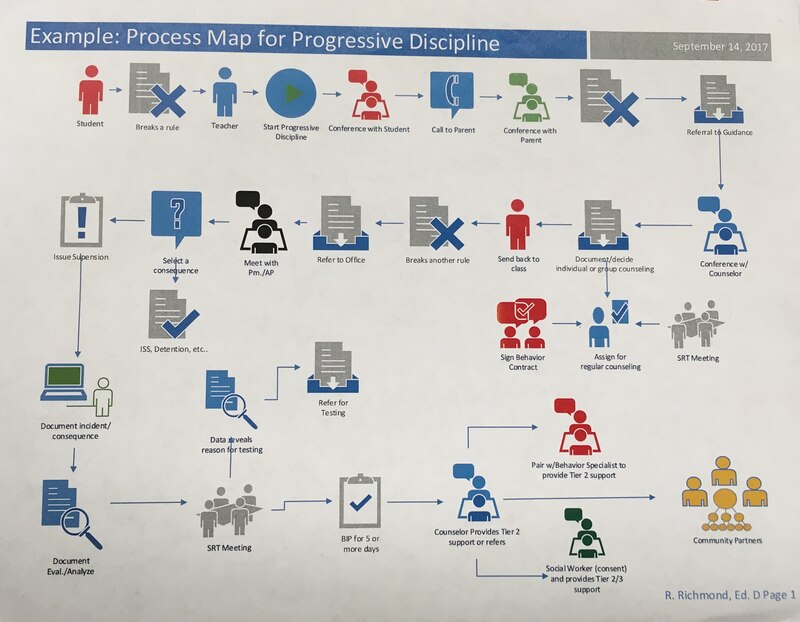

Some actions still must result in automatic expulsion — for instance, seriously injuring a school employee, possessing or selling drugs, and having a gun at school. And the policy for automatic suspensions is also unchanged for fights, assaulting a school employee, or maliciously damaging school property.

In other cases, the goal is to “suspend appropriately” — and not to overlook harmful or disrespectful behavior to make their numbers look better, said JB Blocker, an attendance and discipline hearing official for the district.

“Everything should not result in suspension. And there are a plethora of things to happen before you suspend,” said Blocker. “But I don’t want to go to a school where teachers can get hit in the jaw or stabbed and there are no appropriate, serious consequences. So, we have to find a balance of what that looks like.”

For students suspended for more than five days, state policy requires school leaders to create a behavior plan outlining what is and is not acceptable, strategies, and potential consequences. That practice wasn’t consistent across the district, Spearman said, so behavior specialists have taken that job on.

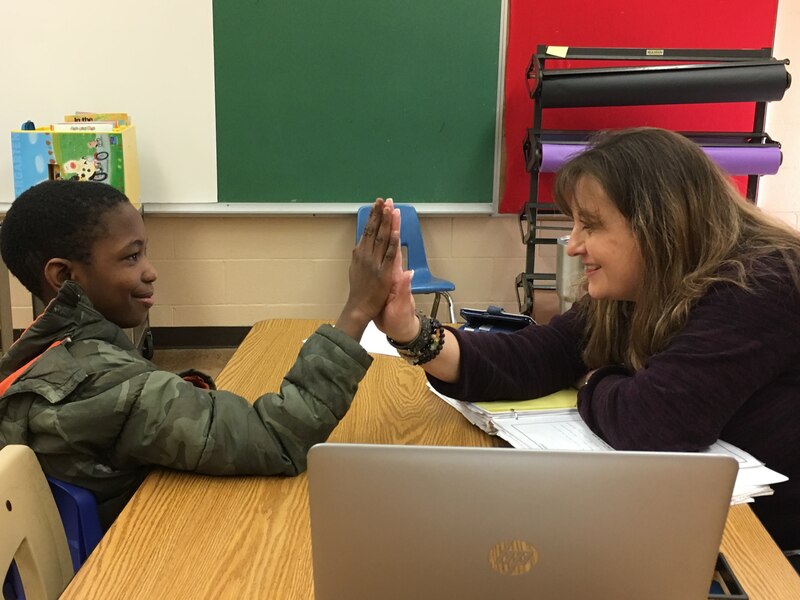

At Gardenview Elementary School, behavior specialist Kimberly Long carries a half-dozen binders in a small roller suitcase, including one with copies of “contracts” students have created to identify ways to improve their behavior — as well as the rewards they’ll receive for meeting their goals.

One Gardenview student wants to erase the teacher’s dry erase board as his reward when he’s done a good job of listening in class and respecting his peers. If he doesn’t, he wrote, his mother should get a phone call from the teacher.

Another student has a sketchbook to draw in when he gets upset. His teacher knows that drawing helps when he needs to calm down.

Weekly check-ins with Long reinforce the behavior lessons that teachers don’t have time to go over individually. She finds that elementary-age students crave attention, and her job is to help them channel that desire appropriately.

“They come here at school and expect that’s what they have to do: act out in order to get the attention,” she said. “They just have to be taught there are other ways.”