More black Memphians have completed high school and college compared to 50 years ago, but those gains have not corresponded with a drop in child poverty.

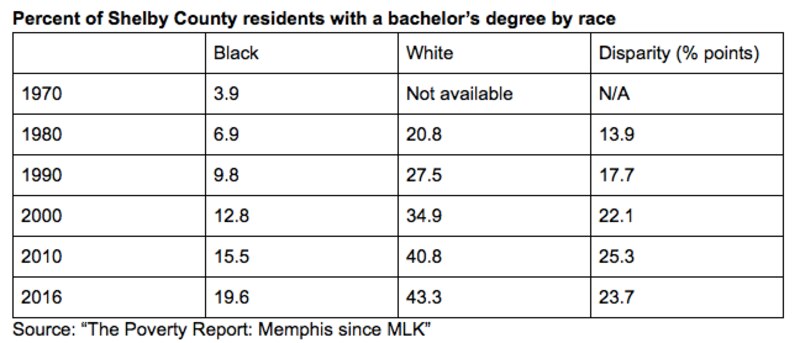

While the percentage of black Shelby County residents obtaining a high school diploma has increased dramatically — and nearly caught up with white residents — the disparity between black and white residents with a bachelor’s degree has risen, according to a newly released report by the University of Memphis and National Civil Rights Museum.

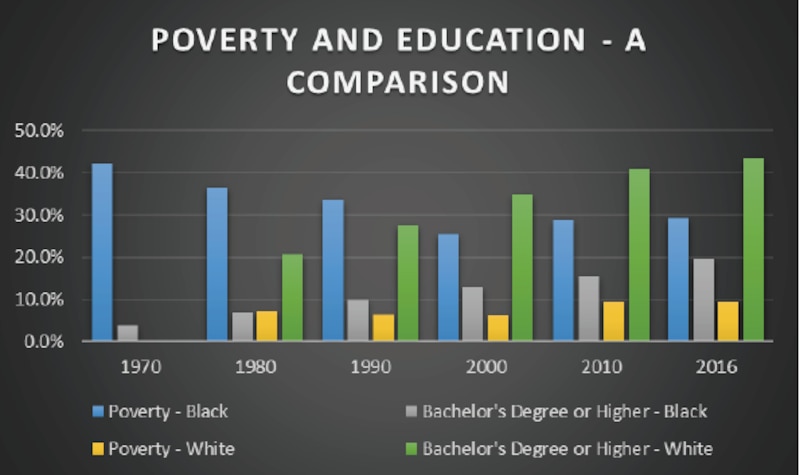

The rise of black residents completing high school corresponded with lower poverty rates in the county until the turn of the century, when a college degree became a more important indicator of future wealth, the report said.

“A high school diploma is helpful only up to a point; beyond that, a college degree becomes necessary for economic progress,” it said.

The report sought to document local changes in poverty, education, employment, and income since the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. 50 years ago next month. King made his final trek to Memphis to support a sanitation worker strike for higher wages and safer working conditions as he prepared to launch the “Poor People’s Campaign” to shift focus to economic equity in the U.S.

The report said it was “embarrassing” that the percentage of black children in Shelby County living in poverty rose from 45 percent to 48 percent since 1980, and that overall child poverty rose from 27 percent to almost 35 percent based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The city was named the poorest region in the U.S. with 1 million or more people last year using the same federal data. The difference in poverty rates for black and white children has increased since 2000.

Educational attainment was highlighted as one of the few areas with tremendous growth for black Memphians.

Since the historic U.S. Supreme Court case in 1954, which ruled laws dictating school segregation are unconstitutional, the rate of black Memphians completing high school rose by 76 percent, narrowing the gap between white and black Memphians from 32 percentage points in 1980 to just under 9 in 2016.

Additionally, the rate of black Memphians obtaining a bachelor’s degree increased from 1.2 percent in 1950 to nearly 20 percent in 2016.

But the gap between the percent of black and white students finishing college has increased since 1980 from about 14 to 24 percentage points. Memphis youth age 16 to 24 are the mostly likely in the U.S. to not be in school or working, according to a 2015 report by a research group that studies economic opportunity.

While more white students in Shelby County also finished high school and college, the increased educational attainment did not have nearly as great an impact on poverty rates compared to black residents.

“This is an important consideration: education appears to have a greater effect on the poverty rate of African Americans rather than whites in Shelby County,” the report said.

The findings reflect a national report released last month looking back on 50 years of data related to economic racial disparities. The Economic Policy Institute report sought to compare that data to the historic 1968 Kerner Commission report that identified racism as the primary cause of “pervasive discrimination in employment, education and housing.”

Nationally, black people saw dramatic increases in educational attainment, but no progress in homeownership, unemployment, and incarceration compared to white people. The racial disparity for completing high school, however, was lower than in Memphis, with a gap of just 3 percentage points.