How can a wolf change the river? Why doesn’t a cactus have leaves? Why can’t you exterminate bats in Tennessee?

With new state science standards coming to classrooms next fall, these are the kinds of questions students will explore in their science classes. They’ll be tasked not only with memorizing the answers, but also with asking questions of their own, engaging on the topic with their teacher and classmates, and applying what they learn across disciplines. That’s because the changes set forth are as much about teaching process, as they are about teaching content.

“At the lowest level, I could just teach you facts,” said Detra Holmes, who is one of about 300 Tennessee educators leading teacher trainings on the new standards to her peers from across the state. “Now it’s like, ‘I want you to figure out why or how you can use the facts to figure out a problem.’”

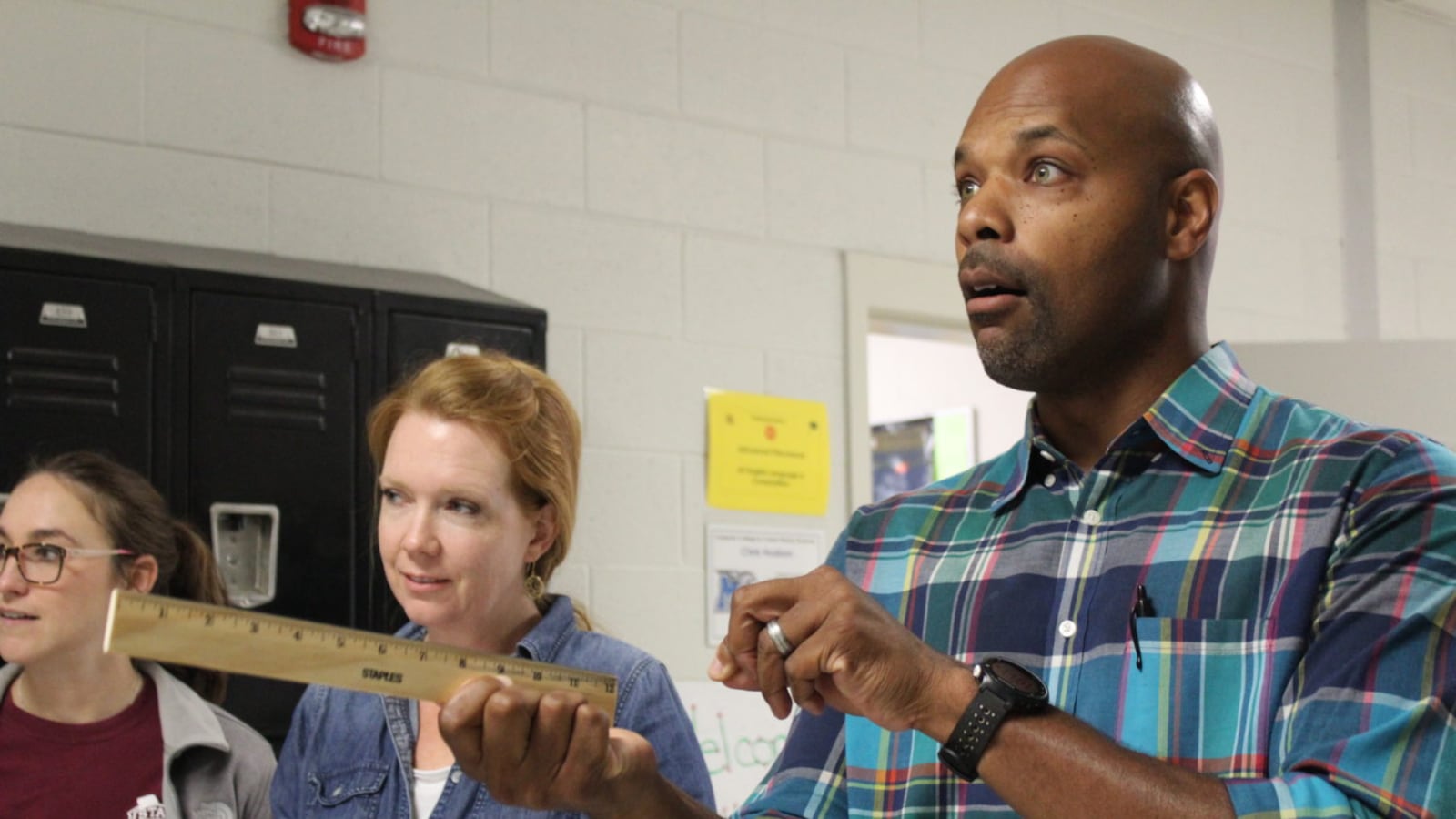

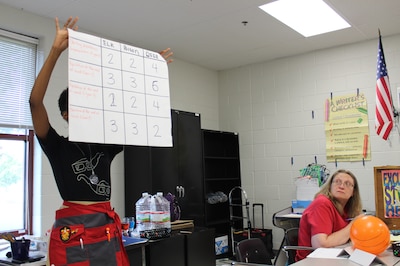

On Wednesday, Holmes — a science coach for the iZone, a group of underperforming schools that Shelby County Schools is looking to turn around — unpacked for her peers, who gathered at Arlington High School, a key component of the new material: three-dimensional modeling. Under three-dimensional modeling, students should be able to do something with the content they learn, not just memorize it.

In recent years, Tennessee students have performed better on state science tests than on their math and English exams. But state science standards for grades K–12 haven’t been updated since 2008. By contrast, math and English benchmarks have undergone more recent changes. To give the stakeholders time to adjust, results from next year’s science test, the first to incorporate the new standards, won’t count for students, teachers, or schools.

At the training session, Holmes, standing before a room of sixth-grade science teachers, held up a chart with the names of woodland animals, such as elk and deer. Under each name, she tracked the population over time.

“At our starting population, what do we see?” she asked.

“The deer, it decreases again because it’s introduced to a predator,” a teacher responded.

“More resources, more surviving animals” another teacher chimed in.

“How can we explain what happened in year two, when we’re dealing with students?” Holmes asked the group.

“The population went up,” a teacher said.

“They start to reproduce!” another teacher interjected.

Holmes nodded.

In another classroom, this one composed of kindergarten teachers, Bridget Davis — a K-2 instructional advisor for Shelby County Schools — clicked through a video of fuzzy critters, each paired with a close relative, such as two different breeds of dogs.

She encouraged the teachers to ask their students what traits the animals shared.

“The first thing they’re going to say is, ‘Well, one’s big and one’s small,” she said. “What we really want them to say is, ‘Well, their fur is the same color,’ or, ‘Mom has a patch of black hair here and the baby doesn’t.’ We want them to look at detail.”

She added, “We want them to get used to being a detective.”

The science standards that have been in place for the past decade fulfills the first dimension of three-dimensional modeling.

Doing something with that knowledge satisfies the second dimension, and the third dimension requires teachers to apply to their lessons a “cross-cutting concept” — strategies that students can apply to any subject, like identifying patterns or sequences.

Under the existing standards, a student may not have been introduced to physical science until the third grade. But starting next year, Tennessee schoolchildren will learn about life science, physical science, earth and space science, and engineering applications, beginning in kindergarten and continuing through high school.

“I do believe that this is the best our standards have ever been, because of the fact that they are so much more detailed than they have been in the past,” Davis said.

About a thousand Shelby County teachers made their way to trainings this week, which were free and open to all educators. Several administrators also met to discuss ways they can ensure the new standards are implemented in their schools.

As with anything new, Jay Jennings — an assistant principal at a Tipton county middle school and an instructor at Wednesday’s training — expects some pushback. But he’s optimistic that his district will have every teacher at benchmark by the end of the 2018–2019 school year.

“We talked before about teachers knowing content, and that’s important,” he said. “But what we want to see is kids knowing content and questioning content. We want to see them involved.”

He reminded other school leaders about last year’s changes to English and math standards, a transition that he said was challenging but smoother than expected.

“Teachers are going to go out of their comfort zone,” he explained. “But it’s not changing what a lot of them are already doing.”

Correction June 25, 2018: An earlier version of this story misspelled the last name of Detra Holmes.