At least four teachers and a school counselor have accused a Memphis principal of pressuring them to promote or graduate students who were failing, according to Chalkbeat’s review of his personnel file.

The teachers said Kingsbury High School Principal Terry Ross told them individually that they must give seniors last-minute makeup work to ensure they graduate — even if students ignored the makeup work they had already been offered or if the student had missed weeks of school. The complaints all came in May, as graduation neared for about 230 Kingsbury seniors. Three of the four teachers resigned over the issue.

Tamara Bradshaw, the school counselor for 12th grade students, said if Ross deemed that teachers had too many students who were failing, he would threaten to fire or reassign them.

“A diploma from Kingsbury is worth very little,” Bradshaw said in an email to the district’s department for employee discipline. “It has been like that for years. The students have been taught to do very little or nothing at all because Kingsbury teachers will pass you. Trust me, it is not by choice that this is done.”

These and other accusations of misconduct and workplace harassment in the past year make up about half of his 210-page personnel file, which did not include any statements or responses from Ross. Chalkbeat obtained the file through an open records request.

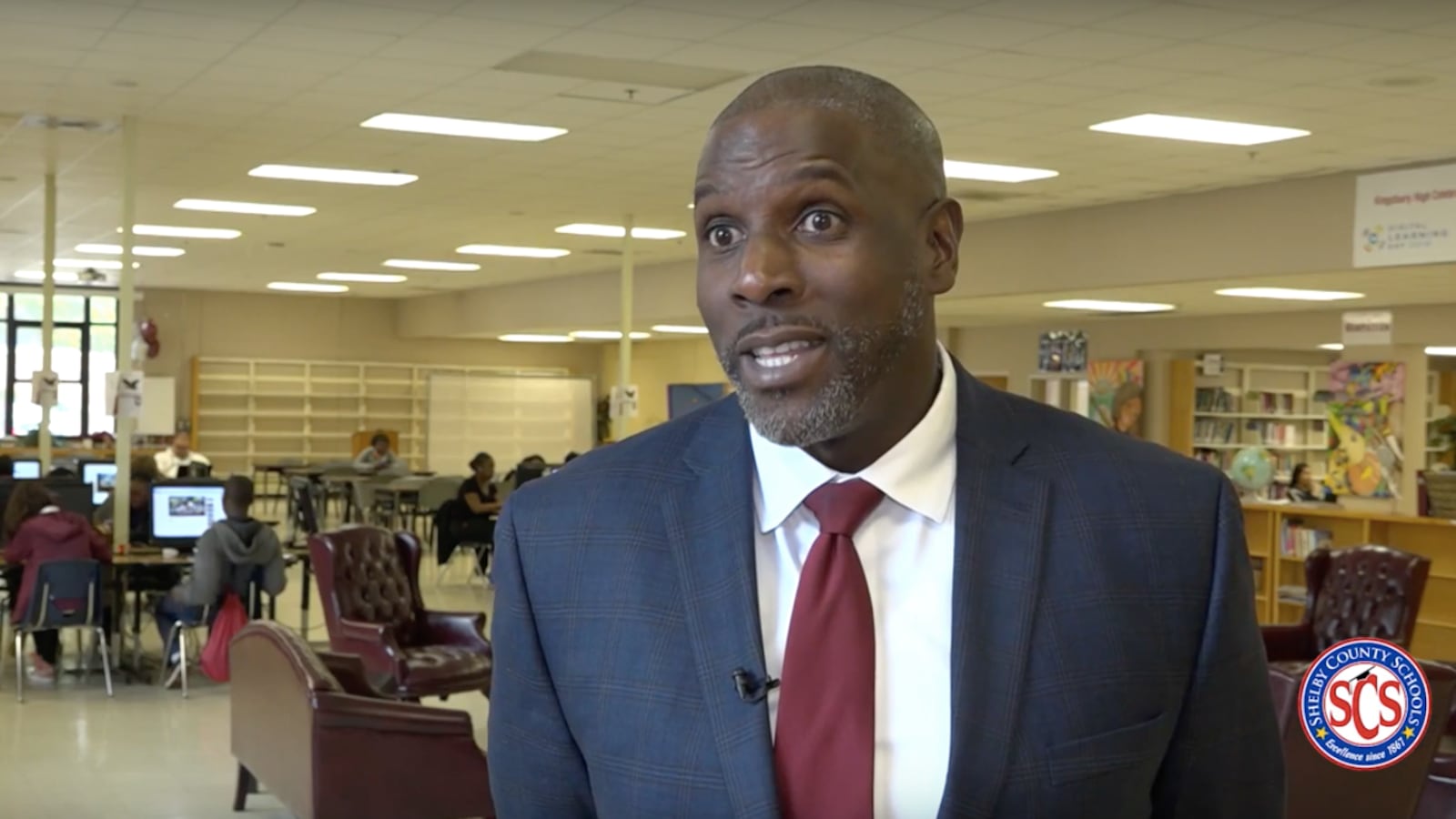

Shelby County Schools suspended Ross with pay last week as a law firm investigates the harassment claims. The accounting firm already tapped to determine if staff at seven Memphis schools improperly changed student transcripts or grades added Kingsbury to its list last month after a former math teacher, Alesia Harris, told school board members that Ross had a hand in changing final exam grades for 17 students to 100s.

The complaints also highlight the shortcomings of corrective measures Shelby County Schools put in place after investigators last year found a “pervasive culture” of tampering with student grades at Trezevant High School.

"The students have been taught to do very little or nothing at all because Kingsbury teachers will pass you."

Tamara Bradshaw

Superintendent Dorsey Hopson has since restricted who can make any changes to transcripts or report cards. But those measures would not prevent principals from pressuring teachers to change grades or assign a flurry of eleventh-hour makeup work to promote or graduate students who show last-ditch effort. Hopson also ordered monthly reports from principals detailing any grade changes and requiring documentation.

Jinger Griner, who had taught English at Kingsbury for nine years before recently resigning, told Chantay Branch, the district’s director of labor relations, that Ross would not accept her list of seniors who were going to fail her class. She said Ross allowed one student who came to Griner’s class only once during the entire spring semester to complete a week’s worth of makeup work “with the intent that she will walk at graduation.”

“I love Kingsbury and I love the students that we serve; they are diverse, spunky, and talented, but, if there are no standards or expectations, then we are setting them up to fail,” Griner wrote in her email on May 16, five days before graduation. “Many of my students could not keep a minimum wage job with the attendance record that they have at school, but unlike that job, which would not give them a paycheck for truancy, we are offering them a diploma.”

"Many of my students could not keep a minimum wage job with the attendance record that they have at school"

Jinger Griner

The accusations against Ross are the latest in a string of complaints of misconduct during the course of his 22-year career in education. When Ross was principal of Getwell Elementary in Memphis in the early 2000s, he was suspended without pay for three days after admitting he violated security procedures for the state’s annual test for student performance. (His personnel file says that he failed to store test materials in a secure manner, and did not report testing improprieties to the central office.)

A retired teacher said last year that students received grades for a fake class that the school said she was teaching months after she left the district, according to local TV station WHBQ, but that complaint was not in his personnel file. And a five-minute segment from TV station WIVB in Buffalo, N.Y., featured teachers who said Ross created an “environment of confrontation and intimidation” at a school he led there just before he took over at Kingsbury High in 2014.

A call to Ross’ cell phone requesting comment was not returned Wednesday. A Shelby County Schools spokeswoman said the district “will not have any further information available until the investigation concludes.” Officials estimated the probe would be completed by the end of this month.

‘We need these kids to graduate’

Students must have a “satisfactory” attendance record to graduate, but specific benchmarks are not listed in district policy. If a student has an unexcused absence, district policy says the student and parent must submit written requests for assignments to make up the work and that “one day of makeup time shall be allowed for each day of unexcused absence.”

But according to several teacher complaints, Ross allowed minimal makeup work in a shorter time frame to count for multiple days of absences. This especially applied to seniors, they said.

Harris, the math teacher, said in her May 10 email to school board members and Hopson that Ross told her “to do whatever it takes to get zeros out” of her online gradebook. Ross encouraged teachers to give makeup assignments during quarterly Saturday sessions known as Zeros Aren’t Permitted, or ZAP, Days. Those sessions are allowed under district policy, but Harris and others said a single Saturday assignment was expected to replace several zeros.

“Many of the students have said they don’t care about missing assignments because they know there will be a ZAP and they will get the zeros replaced,” her email said.

Nikki Wilks, who taught English to sophomores and seniors at Kingsbury, said in a May 15 email to Branch that teachers were expected to use just a few assignments “to cover any and all zeros that a student has in the gradebook.”

Ross would especially pressure her to find “creative” ways to give seniors a passing grade, said Wilks, who transferred to another district school this year. She said she received one phone call from Branch in July to verify a portion of her email, but has not heard any substantial follow up from the district or outside investigators.

“With my sophomores, there was never really a conversation about your failure rates being too high,” she told Chalkbeat. “Then you get these seniors and you’ve got to play cleanup.”

Kingsbury High School carried some of the graduation gains Shelby County Schools has made in recent years. The school had the seventh highest increase of students graduating on time over the past decade, according to a Chalkbeat analysis of graduation rates in Memphis schools. Last school year, about 70 percent of Kingsbury students graduated on time, up from 58 percent in 2008.

That statistic, cited by federal and state education officials when evaluating school quality, is the main reason Griner said Ross pressured teachers.

“We need these kids to graduate because we need to keep our graduation rate up,” Griner recalled Ross as saying during a conversation about some of her students failing. Because Ross did not respond to a request for comment, Chalkbeat was unable to verify this exchange.

De’Mon Nolan, a second-year teacher who taught a creative writing elective, said in an email to the district’s labor relations in May that Ross directed him to “pass all of my students regardless of if they attended school or not.”

“He also told me that my class really does not count, so I should especially pass the seniors,” Nolan wrote in his email to the district. “When I gave him a little push back he is the one who had threatening and unruly comments. I felt that he bullied me so much, I even went home crying one day!”

Nolan told Chalkbeat he estimated about half of his 40 students who were going to fail his class in May ended up graduating without earning the grade.

"I felt that he bullied me so much, I even went home crying one day!"

De'Mon Nolan

“Administration staff came to me and said, basically, I need to figure out how I’m going to pass them,” he said. “I was doing everything I could giving them makeup work. They didn’t come to Saturday school.”

The district declined to extend Nolan’s contract for the 2018-19 school year, which he perceived as retaliation. A few weeks prior, Ross had reported Nolan “sleeping at work, not getting to your classes in a timely manner, leaving students unattended and not coming to (teacher coaching) meetings.” Nolan, in an interview with Chalkbeat and in an email to the district, denied those charges and said Tuesday he has yet to hear from district officials or investigators about his claims against Ross.

‘Like a prisoner in my own room’

Ross’ personnel file also shed more light on Harris’ allegations, presented to the school board in June.

Before the alleged grade tampering took place, Harris and Ross had a disagreement over how to handle a senior in danger of not graduating. Harris said she had given the student makeup work, but he didn’t turn it in. Ross pushed for more makeup work, and when she refused, he said “he will get the student a packet and have someone else grade it if I won’t,” she wrote.

Shelby County Schools dismissed Harris’ allegations as “inaccurate” because the grade changes were a mistake, but declined to release full details of the initial investigation until the current one has finished.

Nicholas Tatum, a special education teacher who sometimes taught with Harris, said he meant to input 100s for students for a first semester exam that was taught by the teacher who Harris had replaced midway through the year. He said he accidentally put them in as second semester scores.

Neither Ross’ personnel file nor district officials offered explanations why first semester grades were edited in May or any documentation that those updated scores were correct. Felicia Everson, Ross’ supervisor, cleared Harris to change back the second semester grades a few days after the incident.

Phyllis Kyle, a union representative for Memphis-Shelby County Education Association, represented Harris and another employee during two meetings with Ross. She told district officials in a May 11 email that Ross was “demeaning, unprofessional and not representative of what leadership looks like in Shelby County Schools.”

Several emails in the personnel file show that Harris and Ross’ relationship continued to grow tense to the point she felt “like a prisoner in my own room,” she wrote to Everson.