Three years after one elementary school joined Shelby County Schools’ flagship school improvement program, Principal Melody Smith says growth is proof their efforts are working.

“We came together we battled, we cried, we fought tooth and nail, but in the end we kept our students in the center,” Smith told teachers as they reviewed the results a week before school began.

A.B. Hill Elementary School, which is part of the Innovation Zone, went from less than 5 percent of students reading on grade level last year to 15 percent in state test scores released Thursday. That jump earned the South Memphis school the state’s highest ranking in growth, but the scores also mean about 85 percent of students still don’t meet state requirements.

The iZone’s two dozen schools have been heralded for how much students have grown since 2012, especially when compared to the state-run Achievement School District, which heavily relies on private charter organizations to boost test scores, and scored the lowest in student growth.

But the challenge is far from over, and school leaders are looking for ways to improve faster.

State leaders generally look at three years of data before determining if academic strategies are working. And in the past three years, the state’s switch to online testing has been tumultuous, which has caused some district leaders and state lawmakers to question the results. But on national tests, Tennessee was held up as a model for student growth compared to surrounding states in a recent Stanford University study — even while the state is still in the bottom half of test scores nationwide.

Only three schools in the iZone — Westhaven Elementary, Cherokee Elementary, and Ford Road Elementary — have more than 20 percent of students reading on grade level. By comparison, 16 schools surpassed that in science, five in math, and four in social studies.

“There was a lot of movement in our elementary schools,” said Antonio Burt, the district’s assistant superintendent for schools performing poorly on state tests. But “we’re going to need a laser light focus on our high schools and our middle schools.”

The district created the iZone to boost student achievement in schools performing the worst in the state, all of which are in impoverished neighborhoods. The state Legislature allowed principals to have much more autonomy on which certified teachers they could hire, pumped about $600,000 per school for teacher pay incentives, and added more resources to combat the effects of poverty in the classroom, such as clothes and food closets.

Now, entering its seventh year, the iZone is still outshining the state-run district, and students are still showing more growth compared to their peers across the state who also performed poorly last year. Nine schools in the iZone got the state’s highest ranking for growth, compared to just five last year when the state switched to a new test. (Scroll to the bottom of this story to compare test scores and growth for iZone schools.)

Of the 23 schools in the iZone last year, seven of them were high schools. None of the high schools had more than a third of students on grade level or above in any subject. Four of them — Raleigh Egypt, Melrose, Mitchell, and Hamilton — saw significant growth in at least one subject. Last year was Raleigh Egypt’s first year in the iZone under Shari Meeks, who previously was principal at Oakhaven Middle School.

Burt said “the first big thing” that will be done to combat low reading scores in middle and high schools will be to strengthen curriculum. Adding curriculum for younger students played a part in boosting test scores that contributed to growth, leaders said.

Also, new reading specialists will teach a separate class for students who are the furthest behind on top of their normal English class. Before, teachers were responsible for catching up those students, or specialists would take them out of class to work on reading skills.

At the district level, Burt said science, social studies, math, and English advisors will be working more directly with teachers. And principal coaches will have more say in how and where those advisors concentrate their efforts.

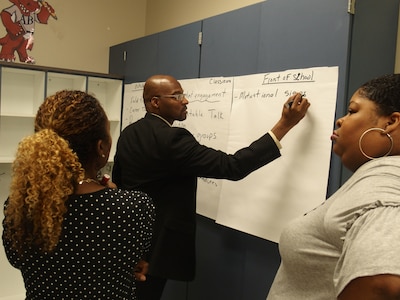

Inside the school, Smith, the principal at A.B. Hill Elementary, said having teachers practice more difficult lessons in front of each other helped spur more ideas on how to make the curriculum work for their students.

Teachers said collaboration with others was key to figuring out the best way to improve test scores there. It was common for teachers to invite each other to sit in on lessons and give feedback.

“We would debrief with each other all the time,” said Brenda Pollard, who taught fourth-grade English and social studies. Now she says the foundation has been laid for higher achievement.

“It can be done,” she said. “We’re living proof it can be done.”

Below is a table of how iZone schools fared on state tests. Fields labeled “4.9” were hidden in state data, but are likely below 5 percent.