This story is part of a partnership between Chalkbeat and the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica. Using federal data from Miseducation, an interactive database built by ProPublica, we are publishing a series of stories exploring inequities in education at the local level.

Alexis Singleton is one of thousands of Tennessee teachers in their early years of teaching. She’s one of 14 new teachers at her Memphis elementary school, and she’s seen firsthand the effect high teacher turnover can have on students.

“My students are already asking me if I’m going to be here next year,” said Singleton, a fourth-grade reading teacher at Treadwell Elementary School. “We’re three months into the school year, and they’re scared already.”

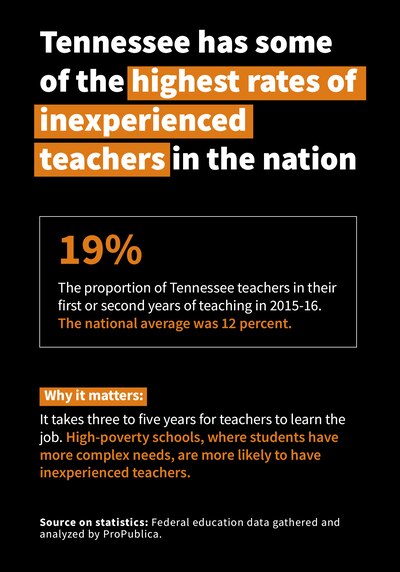

Singleton’s students’ fear is founded: Tennessee has one of the highest proportions of early-career teachers of any state — and people who work in its schools say high turnover in schools like Treadwell is a major cause.

Nearly one in five Tennessee teachers were in their first or second year of teaching in the state during the 2015-16 school year, according to data that schools reported to the federal government. That figure was even higher for Memphis schools.

Shelby County Schools and Tennessee’s education department say they don’t track how many teachers are in their first or second year in the classroom. Schools report that information directly to the Office of Civil Rights, and school-level data was published in an interactive database newly compiled by ProPublica, a national media organization.

Those numbers matter because they mean that many Tennessee classrooms are filled with educators whose skills still have room to grow, as there’s strong evidence that educators improve with experience, especially during their first few years of teaching but even afterward.

That phenomenon affects students of color and students from low-income families the most. In schools with mostly students of color, almost half of teachers were inexperienced, compared with 8 percent of teachers in schools with few students of color, according to an analysis from the Learning Policy Institute.

One way to reduce schools’ need to rely so heavily on brand-new teachers is to get more teachers to stick around. Across the state but especially in Memphis, teacher training programs are increasingly making this the goal.

Alfred Hall knows the challenges of staffing schools in diverse and urban settings. He was a longtime educator in Memphis public schools – a district with more than 90 percent students of color – before becoming assistant dean in the College of Education at the University of Memphis.

“We realize there are specific needs that teacher candidates need support and preparation for if they are going to be successful, particularly in urban school environments,” Hall said. “Many of our teacher graduates are of a different race, cultural background, or economic status than the students they are serving. They have to be prepared to address issues of equity and social justice if they are going to be successful in their classrooms.”

And Hall added that the stakes are high to retain effective teachers in schools where students have the furthest to go academically – many of which are schools in Memphis with high percentages of students of color and students from low-income neighborhoods.

“I know it makes a difference for students to see themselves in their teachers.”

That describes Singleton, who lives and teaches in a neighborhood that is predominately Hispanic and black. Singleton’s mother is Mexican and her father is black.

She moved from California more than a year ago to join the Memphis Teacher Residency, a training program that asks participants to commit to teaching in Memphis for five years. Singleton co-taught with a mentor teacher the first year, and then took on her own classroom her second with additional mentorship support from the residency program.

“I still don’t have everything I need, but at least I have a year of watching, observing and doing before I took on a classroom on my own,” Singleton said. “I think a lot of people don’t realize how high-pressure the profession of teaching can be until you’re in it.”

The University of Memphis College of Education is seeing in their graduates the same thing Singleton is seeing in her school — a lot of new teachers don’t make it to their third year.

“If we get teachers through their third year, we see that they are more likely to sustain and stay in that field over longer periods of time,” Hall said. “We as a university are much more mindful now of our role in helping teachers reach that benchmark, especially our teachers going into urban school environments, where we know retention rates are lower.”

As a result, the University of Memphis launched a new partnership last year with two school districts in Memphis aimed at addressing the problem of retention, as well as teacher recruitment. As part of the partnership, Hall said, the university is establishing a mentorship program with retired teachers for College of Education graduates during their first years of teaching.

The university is also creating “learning communities” for graduates in their first or second years, where groups of new teachers will meet together outside of their schools to support and learn from one another.

“We want young teachers to share and realize that they are not doing this work in isolation,” Hall said. “We know that new teachers may be apprehensive about reaching out to others in their building for help, but we know that it’s very hard to stay in this profession if you are going through it alone.”

Tennessee’s largest teacher organization is also trying to keep young teachers in the classroom through new mentorship opportunities. Beth Brown, the new president of the Tennessee Education Association, said that one of her top priorities during her two-year term is recruiting and retaining early-career educators.

“We know the teaching profession in this state is constantly in churn as teachers leave the profession,” Brown said. “This is highly concerning to me, because I know that as a teacher, I got better every year. It’s like fine wine and cheese. It’s not that young teachers aren’t doing a good job, because that’s not what I’m saying. It’s that you get better with experience.”

Brown said she’s going to work closely with districts and encourage them to put more resources into mentorship programs.

“When an educator graduates from college and gets their first job, don’t throw them to the wolves and say good luck,” Brown said.

For Singleton, she said the mentorship from her coach at Treadwell Elementary and from her residency program has helped her immensely during the first few months of this school year. She also said she plans to stay long enough to shed the “inexperienced teacher” label.

“I feel genuinely called to this work,” she said. “There’s a lot of pressure in this job, and it’s the toughest thing I’ve done. But I live and work in this neighborhood. I believe in it. I guess I think, if I don’t do this work, then who is going to? That makes me want to stay.”