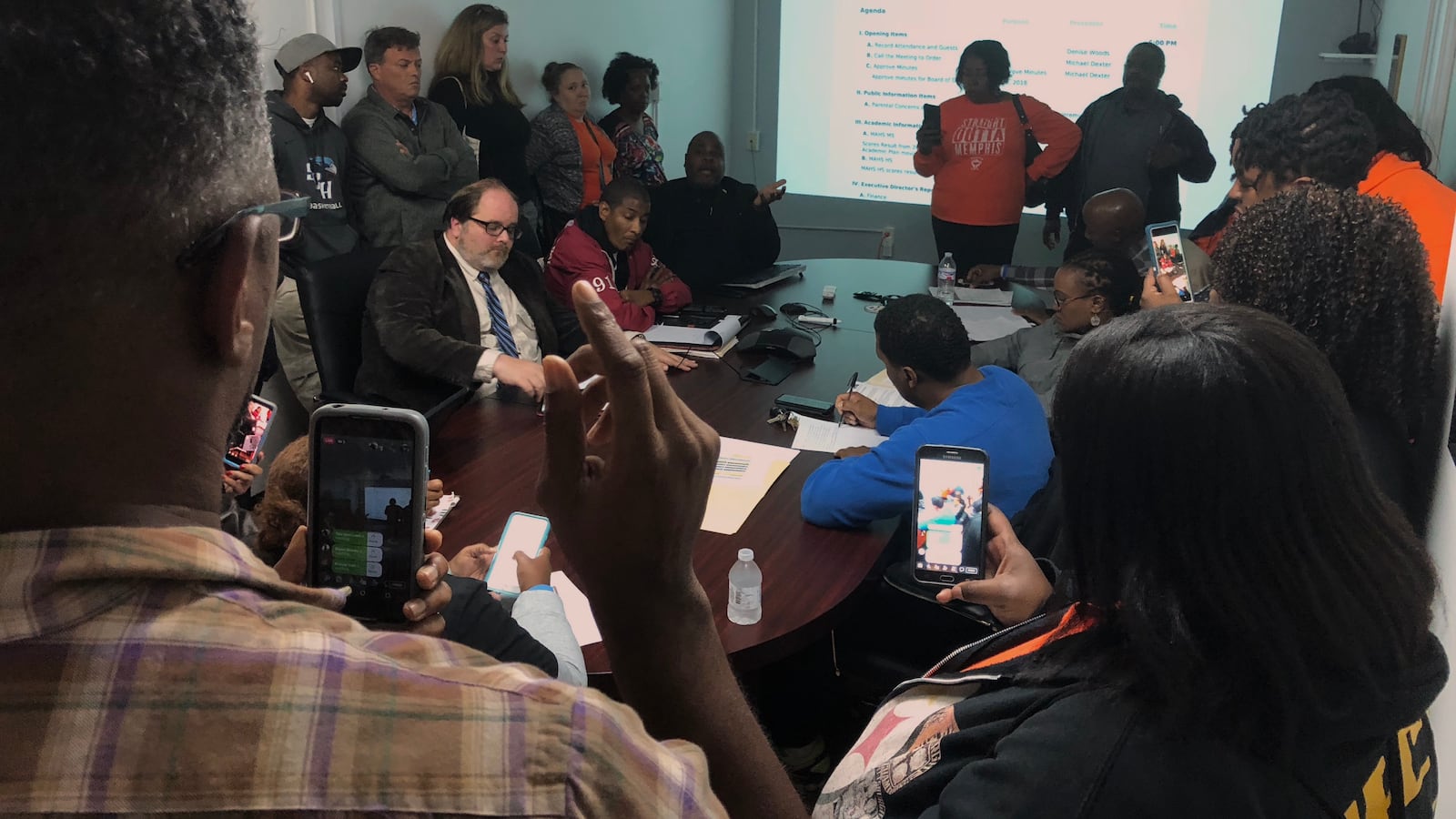

About 20 Memphis parents and their supporters lined a small conference room after being initially blocked from a charter school’s board meeting to learn more about why a beloved principal was gone eight days into the school year.

The answers were not clear, and after an hour of sometimes heated exchanges, advocates threatened to encourage parents to pull their children out of Memphis Academy of Health Sciences, the high school Reginald Williams ran for four years.

Williams’ last day was Friday, Aug. 10. Parents said a letter sent home with students on Monday, Aug. 13, announced the principal had resigned. But on a speaker phone during the meeting, Williams said he did not resign. Corey Johnson, the school’s executive director, said Williams’ departure was a “mutual agreement.”

“We cannot speak on what happened with Brother Williams, OK? So, let’s move on,” board chair Michael Dexter told parents.

Parent Eric Jackson followed up with a question that was met with eight long seconds of silence from board members.

“Are we allowed the opportunity, or is he allowed the opportunity, without reprisal, to tell us, if I get in contact with him, what happened?”

Patricia Ange, a Memphis Academy teacher who prepares students to take the ACT college readiness test, then called Williams during the meeting and put him on speaker for everyone in the room to hear.

Williams said the board’s decision to fire him was their choice. But he said, “If I’d known in the summertime, I could have found another place.” Williams, a former principal at Kirby High School and assistant principal at Central High School, added, “Now I’ve got to draw unemployment.”

“So, you did not resign, sir?” Ange asked as parents hushed each other to listen for the answer.

“No,” Williams said to parents’ amazement.

Williams said he had planned to retire in May, and was not told why he was fired, but suspected negative state test scores were a factor.

TNReady test scores at the 15-year-old high school in North Memphis declined in every subject last school year. For example, 6.2 percent of students were considered on grade-level by the state compared to 33.6 the previous year.

Williams blamed the charter network’s late purchase of laptops, which prevented students from practicing online, and the myriad technical problems with the state test this spring. State lawmakers banned using the scores in decisions to hire, fire, or compensate educators, and only allowed school boards to use them for up to 15 percent of a student’s grade.

Johnson maintained the decision for Williams’ departure was mutual and that he “wanted to support him in his decision” to retire earlier than planned.

Memphis Academy, which enrolls about 400 students, was one of the first schools chartered by the Memphis school district. It was founded by the nonprofit group 100 Black Men of Memphis. Inc.

Charter schools in Tennessee are funded by public money, but nonprofit boards of directors run the schools. The schools are overseen by local districts or the state — in this case, Shelby County Schools. State law states that board meetings are open to the public.

But Sarah Carpenter, leader of the parent advocacy group Memphis Lift, said the board blocked access to the regular quarterly meeting for about 30 minutes. Dexter said there was confusion about when to allow parents inside. He initially wanted to wait until after board members approved minutes from the previous meeting, but after reviewing the board’s bylaws, he allowed parents to enter.

Dexter said one of his goals for the school year was to form parent committees to work with the board. Parents present at the meeting said the effort was too little, too late.

“I can’t believe you don’t know what’s going on,” parent Golding Calix told board members through a translator. “You say you’re listening, but are you going to do something?”