When then-newly appointed Education Commissioner Candice McQueen began touring Tennessee schools in 2015, she was “ashamed” of the dearth of strong reading materials available for many students and their teachers.

“Depending on what districts and classrooms you were in, some people had resources and curriculum and some did not,” recalls McQueen, a former classroom teacher and university dean of education.

The shortcoming was just one of several that helped explain Tennessee’s stagnant reading scores and why only one in three students was considered proficient in reading, based on national tests.

There also was a gap in how teachers or teacher candidates were being equipped to teach reading, a lack of attention to fostering reading skills in students’ early years, and little to no public education programming to address “summer slide,” the tendency for especially low-income students to regress in academic skills during their summer break from school.

McQueen has sought to address all of those weaknesses through various investments and supports under Read to be Ready, which was her first sweeping initiative under Gov. Bill Haslam.

Now, as she winds down her four-year tenure this month, the outgoing commissioner considers that work — launched in 2016 with the support of Haslam and his wife, Chrissy — among her most important legacies as education chief.

Last week, as a fitting bookend to her statewide leadership before starting her new job as CEO of a national education organization, McQueen put reading front and center during three days of regional gatherings of teachers and literacy coaches in Memphis, Nashville, and Knoxville.

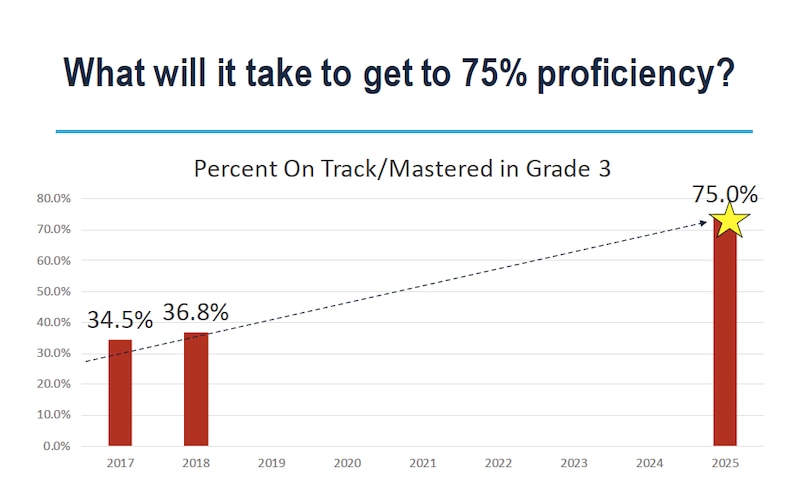

“We’re just now beginning to see progress on TNReady,” she said of last year’s reading gains in grades 3-5 on the state’s standardized test.

“It’s progress we’re proud of, even though it’s not as much as we want,” she added.

Indeed, the climb ahead is steep, despite this year’s 2.3 percent increase to almost 37 percent of third-graders reading on or above grade level. To reach Tennessee’s lofty goal of 75 percent by 2025, the state will have to move 5 to 6 percent more third-graders to proficiency every year.

McQueen says reaching the goal is “absolutely doable” and cites the groundwork laid through Read to be Ready. Since 2016, Tennessee has launched a statewide coaching network for elementary reading teachers, offered new training for educators, and made investments in better resources for students. There are also new standards and expectations in teacher training and summer reading camps for first- through third-graders who are furthest behind.

McQueen is especially encouraged by summer camps that have shown statistically significant reading improvements for participating students during the past two years. She recently announced $8.9 million in state grants to 218 public schools to host even more camps next summer.

As for the lack of high-quality textbooks and materials she first encountered in 2015, the state has identified texts that align with Tennessee’s new academic standards, and McQueen is urging districts to plan now to budget more for them.

“We’re building in this idea that you don’t just adopt; you purchase,” she told Chalkbeat. “Sometimes we see adoption where you have a set that all teachers are sharing. We feel like every teacher needs their own sets of books, their own curriculums, so they can adequately support all their students.”

Recognizing that strong reading skills are the foundation for learning and success in all subject areas, most Tennessee’s districts have embraced some or all parts of Read to be Ready. It’s popular as well with teachers, who say they like having both guidance and flexibility to help their students learn to decode letters and words, expand vocabularies, and deepen comprehension skills.

“This makes concrete resources available, but we’re also empowered to use our own teacher resources,” said Emily Townsend, who teaches kindergarteners in Coffee County.

Others are concerned that the focus on young children is coming at the expense of struggling middle and high school readers. “These are not throwaway kids,” said Stephanie Love, a board member for Shelby County Schools.

Love said the effects of poverty are also at play and require a deeper look at illiteracy in large cities like Memphis.

“I don’t think we need more initiatives; I think we need to reevaluate and see what’s preventing so many of our students from reading well,” said Love, a proponent of more state funding for schools. “Do they need glasses? Are they dyslexic? Did they not attend a pre-K or Head Start program?”

McQueen agrees that illiteracy is a “true equity issue.”

“Reading skills are a predictor of so many things across a lifetime,” she said of navigating school and jobs and avoiding crime and poverty. “We know that if you’re not reading proficiently by the third grade, you can still catch up, but it gets harder over time. Our passion for this work comes from what we know happens when kids are not reading.”