Sonya Thomas met a handful of fellow Nashville parents last summer, and quickly realized they all had something in common – a deep dissatisfaction with the schools their kids were attending.

Thomas said they wanted to do something big and drastic, something more than just talking about it. But they didn’t know what that was until they met Sarah Carpenter, a vocal Memphis parent and leader of advocacy group Memphis Lift, at a Nashville parent summit.

“The thing that most stood out to me, is how much they help their other parents,” said Golding Chalix, one of the leaders of the new parent advocacy group Nashville Propel. “To me, that was really inspiring to see parents fighting and working toward goals in a more organized way, especially being a Latina mom wanting to fight this fight.”

Nashville is the latest city to copy pieces of the Memphis Lift model. Carpenter said she’s been meeting with parents in Oakland and Atlanta to help get their programs started. An Indianapolis nonprofit launched an advocacy fellowship earlier this year to give low-income families and families of color more voice in their local schools – and pointed to Memphis Lift as one of the model examples of parent engagement work.

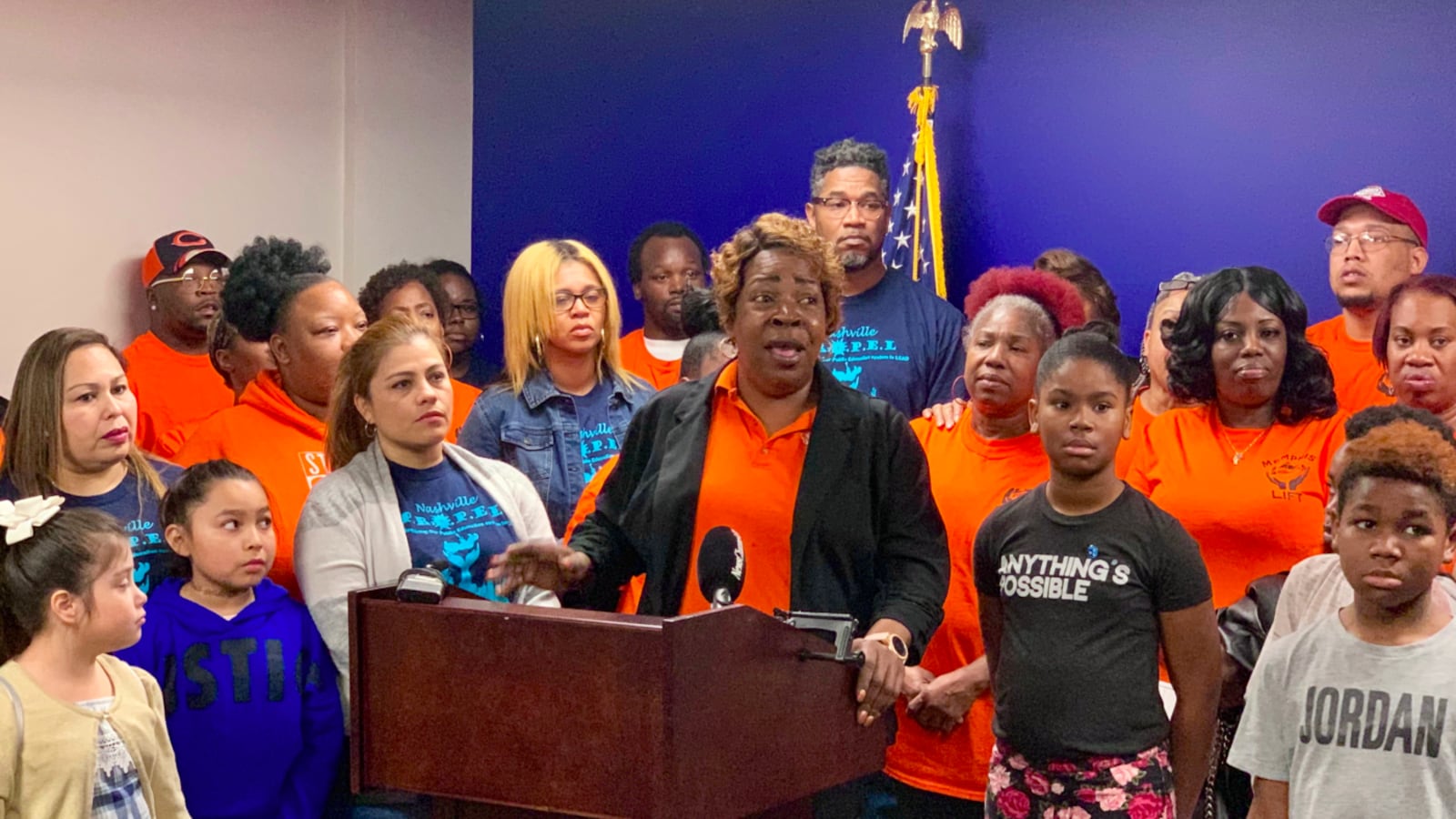

The handful of parents that make up the backbone of Nashville Propel started meeting last fall, and held a joint press conference with Memphis Lift last week at Capitol Hill to talk about their priorities, which hinge on educating parents of students in Nashville’s lowest-performing schools.

Memphis Lift has had success in reaching parents door-to-door and building a grassroots support system through its own advocacy fellowship. The group has held dozen of events at its North Memphis headquarters, at schools, and has shown up in force to school board meetings as its sought to rally parents.

Carpenter, who helped start Memphis Lift in 2015, said the national interest started three years ago when she spoke at a Teach for America event.

“Our phones have been ringing off the hook since,” Carpenter said. “It’s awesome to connect with other parents like this who have the same problems. They’re regular parents just like us trying to make a change in their city for low-performing schools.”

Thomas said the Nashville group is copying Memphis Lift’s strategies in door-to-door outreach and from its Public Advocate Fellowship, which was created three years ago by Natasha Kamrani and John Little, who came to Memphis from Nashville to train local parents to become advocates for school equity.

When Memphis Lift launched, it was viewed warily by some local school leaders who doubted the group’s independence because of its close relationship with Kamrani, former director of Tennessee’s branch of Democrats For Education Reform and wife of Chris Barbic, founding superintendent of the Achievement School District. Little ran Strategy Redefined, a Nashville-based education consultant firm that helped launch Memphis Lift.

The Memphis fellowship has trained 327 members, mostly women, since it launched in 2015 on how to navigate an increasingly complex school choice system and how to understand state data on schools. This past year, Memphis Lift offered training for Spanish-speaking parents and is working to create its first all-male cohort for fathers and grandfathers.

Nashville Propel just finished its first parent fellowship, which was completed by 29 English and Spanish speakers. Thomas said a big goal for Propel is to help parents understand what it means that their children attend priority schools, the state’s designation for Tennessee’s lowest-performing schools.

“We’re finding parents don’t clearly understand what this means,” Thomas said. “Some even think priority school means their school is doing well. Once we explain it to them, they realize the gravity of it.”

With neighborhood events over the last few months, Nashville Propel has spoken with about 700 priority-school parents. Within a year, the group wants reach 4,000, which is 75 percent of Nashville parents whose kids go to low-performing schools, Thomas said.

Tremayne Haymer of Nashville Propel said they are going to advocate for Metro Nashville Public Schools to release a public plan for the city’s 21 priority schools. Six Nashville schools were on the list in 2012.

“From 2011 to now, every time the list comes out the number gets greater,” Haymer said. “We’re going to be in the same boat Memphis was in a few years ago. Our plan is a year from now to get clear-cut resources from the district on how to combat this problem.”

Unlike Memphis Lift, Nashville Propel does not yet have a full time staff, but Haymer said they are actively looking for funders. Haymer added that Propel has gotten some startup funding from the Scarlett Family Foundation, which focuses its education philanthropy on Middle Tennessee.

Memphis Lift has received $1.5 million from the Walton foundation since 2015, and its fellowships are funded in part by the Memphis Education Fund. (Chalkbeat also receives support from local philanthropies connected to Memphis Education Fund and The Walton Family Foundation. You can learn more about our funding here.)

Despite initial leeriness toward Memphis Lift’s funders, the group has criticized and supported both district and state-run schools over the years, such as marching against the closure of an Achievement School District charter school and lobbying county commissioners last year for more funding for Memphis’ traditional school district.

“If it’s a charter school not working, close it down,” Carpenter said. “If it’s a district school not working, do the same. We want it shut down, period. We know what our children deserve in an education.”

Thomas echoed the sentiment.

“We’re not pro-traditional schools, private schools or charter schools,” Thomas said. “We have no other agenda except empowered parents whose children are taken care of.”