With its funding expiring, a Memphis program for students coming out of juvenile detention could end soon, despite a three-year record of job placement and low recidivism.

The $1.2 million federal grant for Project Stand expires this summer. The U.S. Department of Education, which funnels Justice Department funds to programs, has not announced any plans to renew grants for the four participating cities. Shelby County Schools has not yet decided if the district will pick up the tab.

An Education Department spokeswoman would not explain why the grant is not being renewed.

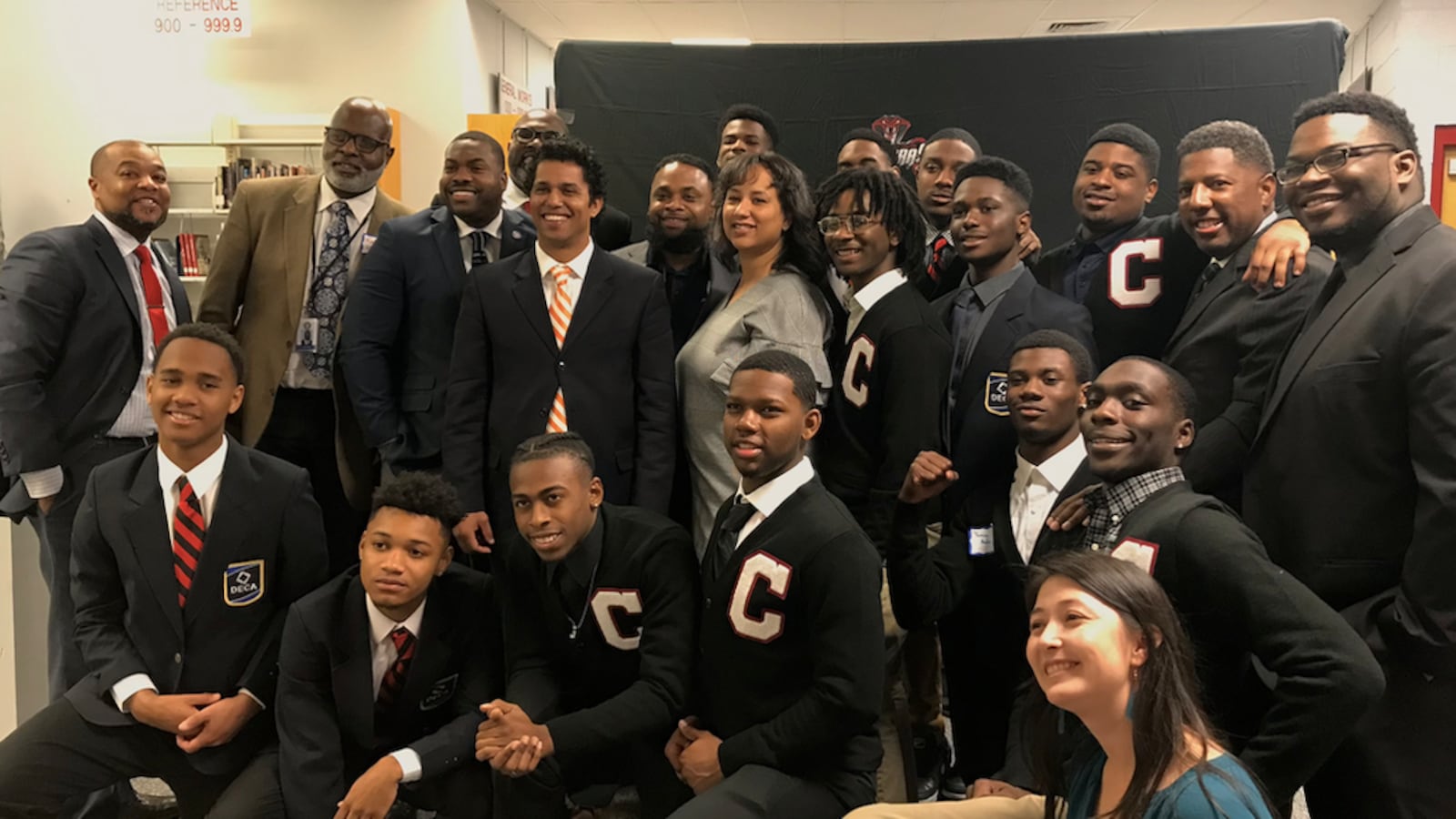

Of 156 students enrolled over its three years, fewer than 10 returned to detention — a 94 percent non-recidivism rate. Of last year’s 32 seniors, 31 are in school or working; one died.

All students in Project Stand take the National Career Readiness Certificate test that is required to work at many companies straight out of high school. About 76 percent of students pass, said Tarol Clements, the manager of Project Stand. That’s particularly important in Memphis, which has the nation’s highest rate of young adults ages 16 to 24 not in school or working, according to the Social Science Research Council’s Measure of America project.

Program leaders and a few Memphis students traveled to Washington D.C. last month to give federal officials an update on the grant, where they said U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos personally congratulated them on their progress.

“We hope that this will be a model, a mentor-based program, to be used in other schools,” Clements said. “You need somebody that’s not the teacher, not the principal, that helps them.”

“Like a second family, basically,” said senior Cameron Al-Wali.

If the program is cut, youth returning to school from lockup will have fewer resources to keep them out of trouble.

The program could disappear even as county officials are divided on how to end mistreatment of youth in custody. For that problem, Shelby County’s juvenile court was under federal oversight until October, when the U.S. Department of Justice abruptly withdrew as a watchdog, even though the court had not met all benchmarks of its agreement.

Project Stand — named for Student Transition, Acceleration, and NCRS (National Career Readiness Certificate) Demonstration — focuses on getting students jobs while in high school and certified for jobs afterward.

The students attend G.W. Carver College & Career Academy, an alternative school with about 200 other previously expelled students.

Project Stand students praised its morning advisory class, where teachers check in with students about how they’re doing, do get-to-know-you activities, or share character-building lessons.

Principal James Suggs said the school seeks to meet the human needs of some of the district’s most fragile students at the beginning of the day before diving into academics.

“We have students who may not get to school until 9 o’clock because [city] buses in this neighborhood only run once an hour,” Suggs said. “Some students may not have working water [at home], so we get them soap, water, and a shirt so they can go in and just wash up before they actually get their day started.”

During a recent morning advisory period, students talked about a recent visit to University of Tennessee in Knoxville and Job Corps in Bristol, which offers certification in fields such as automotive and machine repair, construction, finance and business services, health care, hospitality, and information technology.

Al-Wali excitedly told classmates about meeting a Job Corps student who earned $20,000. “So, whatever he decided to do, he got some money to buy him a car, get some furniture, and an apartment.”

Project Stand students also learn coping skills.

“We got to know how to deal with [depression] or go to the people who know how to deal with it. Stop keeping stuff bottled up; it does not help you,” teacher Arletta Burse told an advisory class discussing mental health and counseling.

About 37 percent of children in Shelby County have experienced two or more traumatic events, higher than the national average, according to the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health and the Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health.

The program’s three coordinators make themselves available to their students via text or phone calls. Their ready guidance sometimes has meant redirecting a student’s spontaneous decision that had potential to land them back in juvenile court.

“My personal life is their personal life. I’ve had Mr. Gorea call me on the weekend just to see how I’m doing. I’ve had Mr. Collier call me to make sure I’m going to work,” Al-Wali said, referring to two staff members. He added that he never had a grade point average above a 3.0 until he started the program. “One thing about them: They’re not going to tell me something they wouldn’t do for themselves, with their own children.”

The students mentor middle school students at Airways Academy, another alternative school, and run a food pantry out of Carver Academy, to provide a community service and learn business skills. The academy will also be a site for the city’s youth employment program this summer.

“We are the school of second chances and sometimes third and fourth,” Suggs said. “When you come through this door, forget about what happened before you got here. You come here, you got a fresh start, you got a clean slate, and let’s make the best of that second chance.”