State lawmakers lashed out at Tennessee education officials Monday and asked them to halt awarding millions of dollars in early childhood intervention grants after the state’s new process shut out many local providers — some of whom had received the state aid for 30 or 40 years.

Nearly half of the 35 longtime providers from around the state lost their state contracts in the latest award period in the Tennessee Early Intervention System, which provides educational services for children under the age of 3 with disabilities or developmental delays. The state intends to award a total of $19 million annually over the next five years to just 19 agencies providing early intervention services, including $3.2 million to Indiana-based provider Benchmark Human Services, according to information provided by the education department.

The funding for the out-of-town provider rankled lawmakers and local providers alike.

Providers said the state’s new process failed to take into account applicants’ decades of offering quality services or their strong community connections and support. Other providers who were used to receiving the grants may have not have fully explained the scope of their programs and services in their applications.

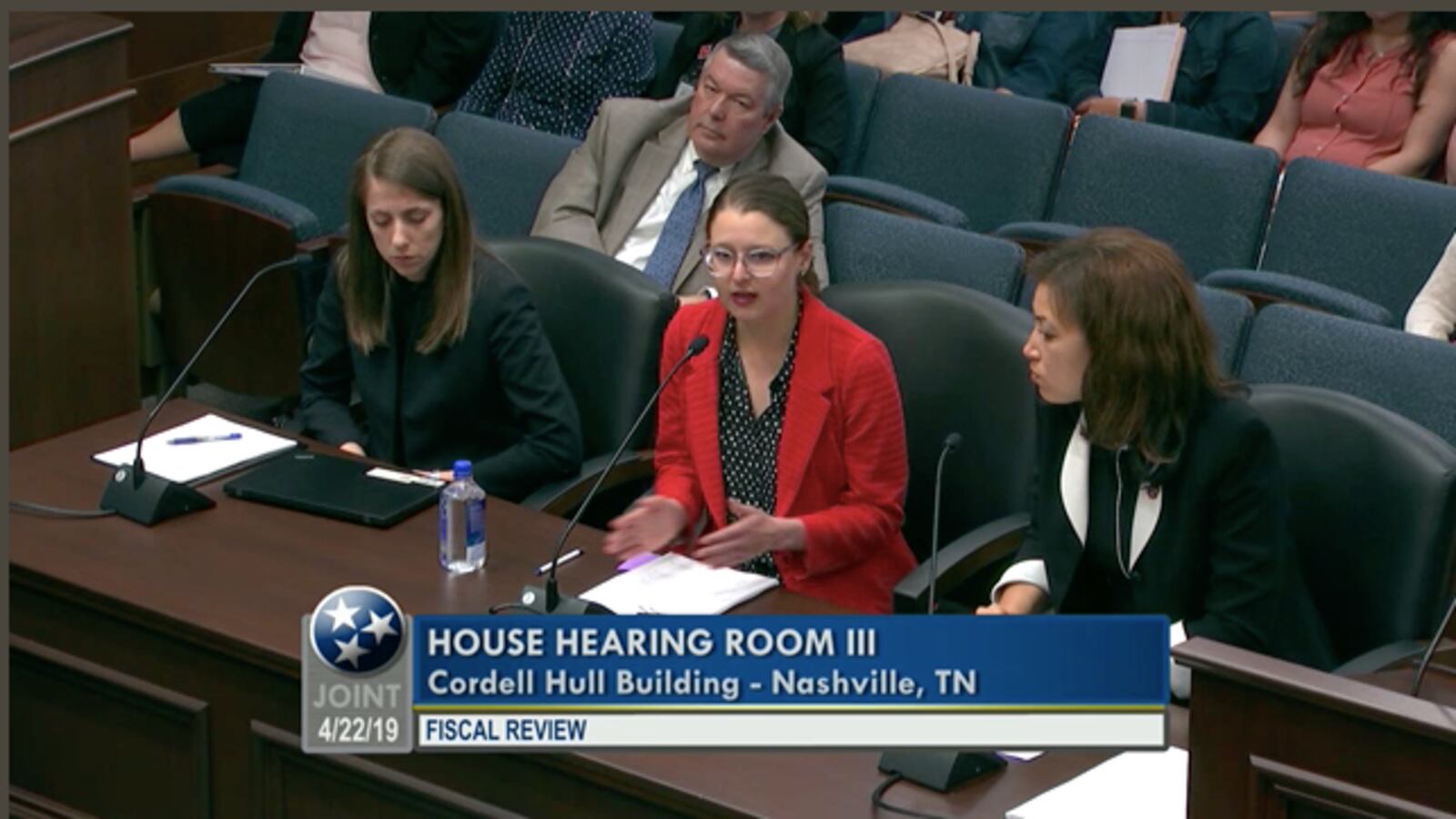

The legislature’s joint Fiscal Review committee voted to request the Department of Education delay or suspend the grant award process and create “a new and clear and objective application process that includes a clear grading matrix.” In the meantime, legislators asked that the current contract grants be extended.

Mike McElhinney, president of the Michael Dunn Center in Roane County, accused the education department of trying “to Walmartize the early intervention system, sacrificing years of quality, history, service, and local support in order to save a few pennies.”

He said his program has operated with the state contract for 48 years and has never received a negative audit or reviews and is rated a “star agency” in the system.

Tyler Hampton, executive director of SRVS [pronounced “serves” and stands for Shelby Residential and Vocational Services] in Memphis, said his organization has provided services for over 20 years. Last year, SRVS provided services to more than 240 children per week in Shelby, Fayette and Tipton counties.

The organization proposed serving 300 children, but instead, he said, the state reduced its grant to serving 200 children in Shelby County only. That will likely force children in Fayette and Tipton to start over with new therapists, Hampton said.

Legislators grilled department officials on why they made the changes and criticized the new process as being subjective.

Sen. Ken Yager, a Republican from Kingston who also serves on the board of the Michael Dunn Center, complained that the provider scores in the grant evaluation were “all over the chart.”

“There are some folks who scored high that didn’t get the grant; there are some awardees that scored lower that got the grants. There is just absolutely no consistency.”

He expressed incredulity when he asked education officials if they had used a template to score the narratives in the applications and they said they had not.

“I’m a retired teacher. Now I’m not as smart as you are or some of the people in this room, but when you’ve got a test to grade, you have an answer key. So if you didn’t have a template to guide the four anonymous reviewers who read these, how did you expect a consistent result?”

It was Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn’s first time in the hot seat with legislators. She mostly deferred to upper-level managers since grantees were selected before she came aboard in February.

Assistant General Counsel Joanna Collins said the department had sought to develop a competitive process that measured quality.

“So rather than just providing basic information about how many children can you serve, what region are you in, what is your budget capacity, we wanted to make sure that the questions in the application reflected quality,” Collins said.

Those quality questions included asking applicants to explain how they would provide services, she said. She also noted that on questions where long-term providers could have excelled, such as detailing their experience, some applicants simply cut and pasted their answers from the scope of services described in the grant solicitation document.

Collins said no vendors, including Benchmark, sought the state’s guidance in completing their applications, although they could have. The only questions the department received were concerning the deadline and insurance requirements.

In the past five years she has worked with the Fiscal Review Committee, Collins said she’s been told that no one is entitled to a government contract and that state law required the state to run competitive processes to select contractors. “That is what we were trying to accomplish here,” she said.

Schwinn acknowledged that there are providers who are “doing great work for kids.” But part of the challenge, she said, is just because there haven’t been concerns with many of the current providers doesn’t mean that there weren’t stronger applications that were submitted.

“I think from the department’s perspective, it’s a really, really difficult situation. We’re putting out a new competitive grant to get the highest quality services for kids, period. And in some cases there were higher quality applications than the good and strong providers that currently exist.”

Schwinn did not say whether she would consider halting the grant awards while her department continues discussing the process.

Correction: April 22, 2019: This story has been updated to reflect that 19 agencies will be awarded a total of $19 million annually to provide early intervention services, including $3.2 million for Benchmark Human Services. An earlier version reported information provided during the Fiscal Review Committee discussions that said Benchmark would receive $20 million from $35 million in grants. The state’s total budget for Tennessee Early Intervention System is $35 million.