Ten charter school leaders in Tennessee’s state-run district are asking the governor not to cut priority school grants in his new budget – approved this week – because they say it could reduce much needed funding for students with special needs.

Every charter leader in the Achievement School District signed an April 16 letter to state Education Chief Penny Schwinn, requesting that Gov. Bill Lee reconsider cuts to the allocation for priority school state grants for next year to $5 million.

The General Assembly voted to approve Lee’s $38.5 billion state budget on Tuesday, which included $39.4 million to fund state schools. As of Wednesday, Schwinn and the state department had not yet responded to the leaders’ letter.

But Jay Klein, a spokesman for the Department of Education, did confirm that the priority school grants had been cut to $5 million, as “it was communicated that this funding was not recurring and it could be eliminated or reduced in future years.” He added that district charter leaders could still reapply for their funding.

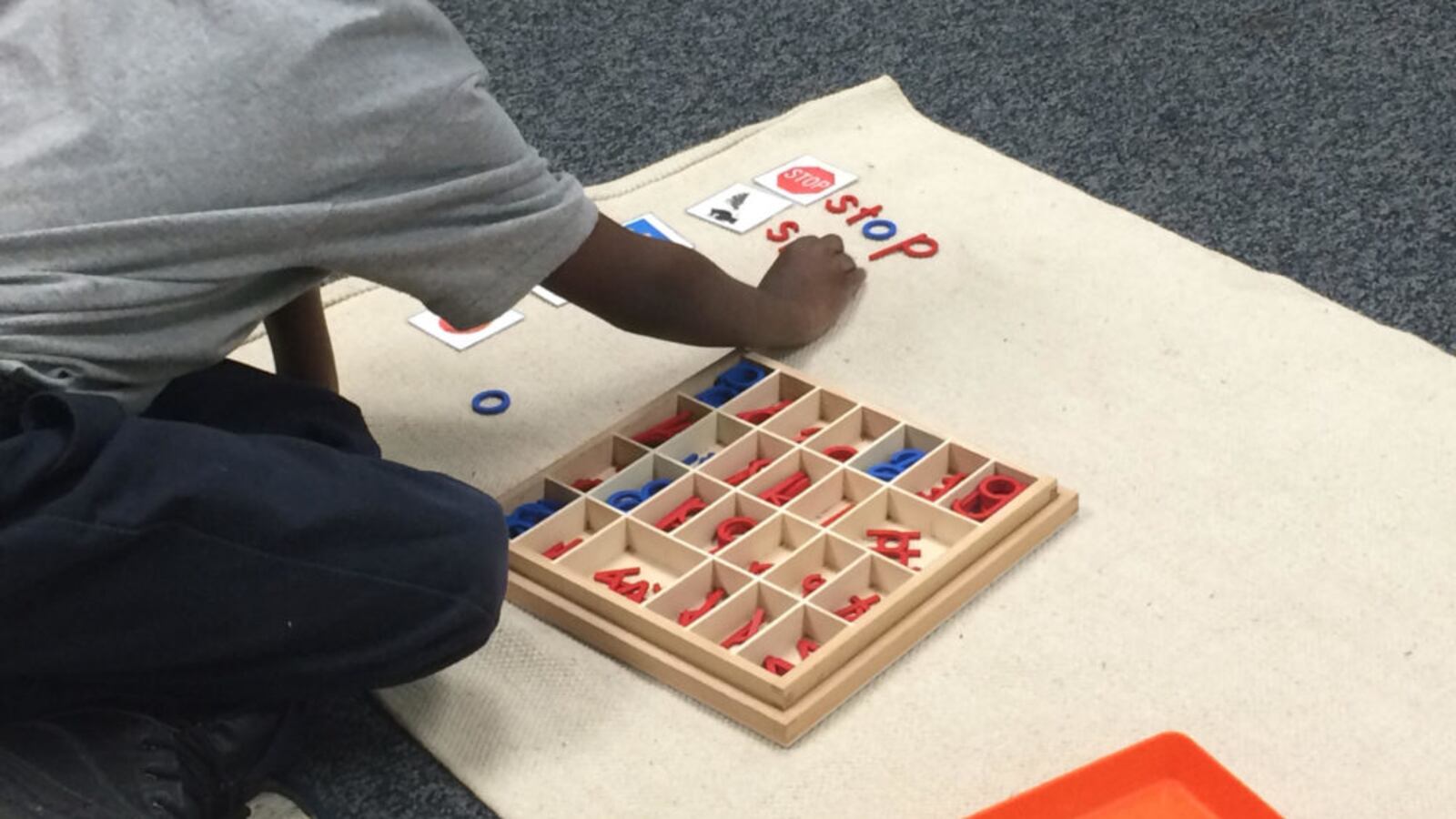

The grant funding is crucially important, the charter leaders say, because students with disabilities can cost schools more to educate well, incurring expenses such as the cost of hiring additional counselors or creating smaller classrooms. Without the funding, charter schools like Libertas School would struggle to give their students with special needs what they need, said Bob Nardo, the Montessori school’s founder and leader.

The funding was started in 2016 at $10 million to help Tennessee schools that were struggling academically. The Achievement School District is made up of 30 of the state’s lowest performing schools, and charter operators are tasked with improving them. Charter schools are publicly funded, but independently run by nonprofit organizations.

From the $10 million grant, about $3 million goes each year to the achievement schools to help with funding for students with special needs. Charter leaders are worried that $3 million will be in jeopardy if the grant remains halved in the 2019-20 state budget.

“The current state funding model doesn’t differentiate funding from say a student with disabilities in a low-income neighborhood to a student in the suburb who does not have a disability,” Nardo said. “That creates an inequity for schools serving a large population of students with disabilities.”

About 23 percent of Libertas students have a disability, according to state data. About 13 percent of students in the achievement district have disabilities, which is right at the state average for all Tennessee districts.

The money allocated to students with special needs goes into a pot of $9 million that all charter operators share. The other $6 million is made up of federal grants and money from the state funding formula. If the grant funding is decreased, charter leaders are worried they won’t be allocated the full $3 million.

“Our model has enabled us to create centers of excellence for special education in the ASD and for adequate dollars to follow children to the programs that fit them best,” according to the letter.

Nardo said that the money has allowed Libertas to build programs for students with severe needs, such as cerebral palsy, that would not have been possible if the school had relied on basic state and federal funding alone. Because Nardo has specialized programs at his school, other elementary schools within the achievement district will send students to Libertas that they don’t have the programming to support, he said.

Leslie Harwell’s son, Bryan, was diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum when he was a first-grader at Libertas. Now, Harwell’s son is a third-grader and she says he has made progress “in leaps and bounds,” thanks to a lot of one-on-one attention.

“You hear horror stories from other parents of their children being left in an empty classroom, throwing fits,” she said. “But we’ve had huge emotional support at Libertas. I have teachers calling me throughout the day with updates on my son…that’s very rare to find.”

Harwell added that her son starts his day in a smaller classroom made up of other students with disabilities before transitioning to a larger classroom.

“The school figured out that if he starts his day in a quieter environment in the morning, that will help set the tone,” Harwell said. “Over the last six months, I’ve seen him grow so much academically. It used to be that doing one piece of homework at night was impossible. Now, he can do four worksheets in no time.”

This isn’t the first time charter leaders have been wary of losing a significant portion of the funding.

“In 2018, after the full grant was approved by the legislature, nearly 20% of the funds were diverted to support other initiatives, such as principal incentive pay,” according to the letter. “When we learned of this adjustment in July, we asked… to refrain from diverting critical funds for special education students, as it could destabilize our progress.”

Sharon Griffin, the achievement district’s leader and direct overseer of four state-run schools, did not sign the letter but was included in the email’s recipients. Griffin did not return a request for comment.

You can read the letter in full below: