Tennessee’s new blueprint for preparing its public school students for college and career reaffirms current priorities like emphasizing early literacy and elevating the teaching profession but adds one major new one: educating the “whole child.”

The approach refers not only to enhancing academic performance but also the social and emotional well-being of children that can lead to better academic performance. It’s one of three main priorities outlined in Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn’s long-promised strategic plan, dubbed “Best for All” and unveiled on Tuesday.

The other two priorities are providing quality academic programs and bolstering the education profession.

The plan sets Tennessee’s agenda for the next five years and will bring new attention to students’ social and emotional health in a state that has given more lip service than funding to that need in recent years. Schwinn had identified support for students’ mental health needs as the top concern that she heard from educators during her statewide “listening tour” after becoming Tennessee’s education chief in February.

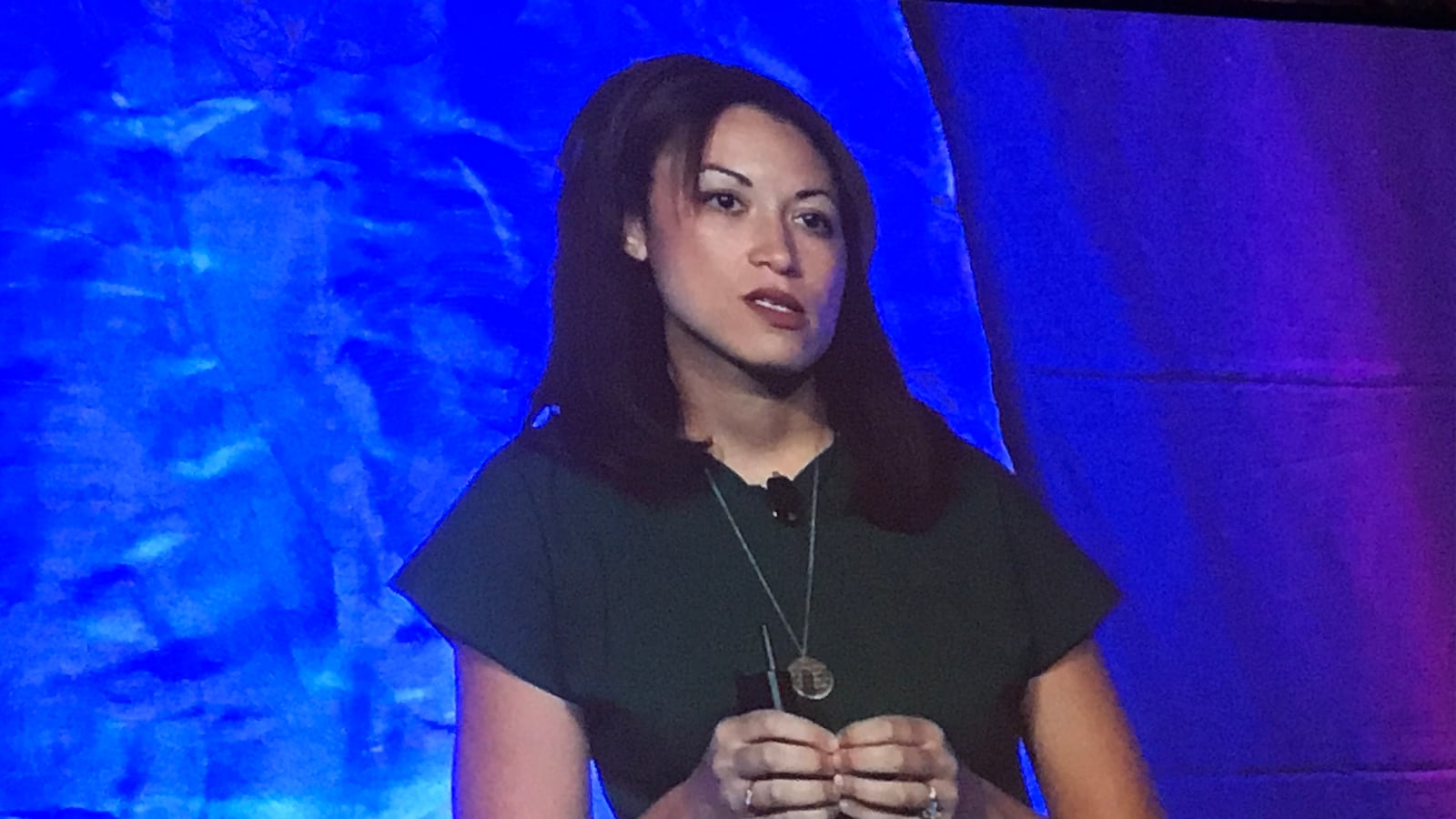

The former Texas academic chief made her case for whole child education as she rolled out the education department’s plan to about 1,500 people attending Tennessee’s annual conference in Nashville for school administrators.

“We have to think differently. It is that urgent,” she said of students grappling with chronic family trauma like poverty, addiction, and abuse. “There are opportunities right now for us to say we’re going to take a national leadership position in this work.”

But exactly what that initiative will look like — and how much it will cost — remains to be seen.

Gov. Bill Lee is holding budget hearings this week with an eye toward next year’s spending plan, and there already are indications that raising teacher pay will be one priority for the 2020-21 fiscal year.

Schwinn’s strategic plan for a whole child initiative was short on details, but she listed the need for character and citizenship education, as frequently mentioned by the Republican governor. She also called for more family tools for special education to support students with disabilities.

“Part of it is going to come down to resources,” she explained later. “What we have rolled out today is to let people know directionally where we are going. I think that the scale and timeline will be aligned after we think about and learn more from the next legislative session.”

The strategic plan also was devoid of measurable goals, which were central to the department’s last strategic plan under which Tennessee has made steady progress since 2015. Schwinn said those will come later.

“For every single one of the initiatives that we rolled out today, we have very clear metrics” to measure how we’re progressing, she said of goals that will be released early next year as part of the governor’s statewide strategic plan.

Addressing the whole child could come with a big price tag, said Joey Hassell, superintendent of Haywood County Schools and a former state assistant commissioner over special populations and student support.

“If we’re going to address things like mental and behavioral health, Tennessee will have to provide training and it will have to provide a lot of funding,” Hassell told Chalkbeat. “We could start by significantly increasing our ratios of social workers, school counselors, and nurses.”

Those school-based helping professionals are generally the first responders to students experiencing a mental health crisis, but administrators say their districts don’t have nearly enough funds to staff adequately for those needs.

Nationally, whole child education is gaining traction. Tennessee is among states that use a traditional health model, as outlined by the Centers for Disease Control in 1987. That model focuses on needs such as physical education, a safe school climate, and access to health care.

A broader approach seeks not only to make students healthy and safe but also engaged, supported, and challenged, said Sean Slade, senior director of global outreach at ASCD, an Alexandria, Virginia-based nonprofit organization that promotes whole child education.

“There are initiatives happening all over the country,” said Slade, citing Illinois, Ohio, and Washington among national leaders.

Levels of investment can vary, he said, and training can be incorporated into existing professional development opportunities.

“One of the things we learned from the federal No Child Left Behind law is that a one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t always work when you’re talking about different states, different schools, and different contexts,” Slade said.

You can learn more about the department’s “Best for All” plan here.