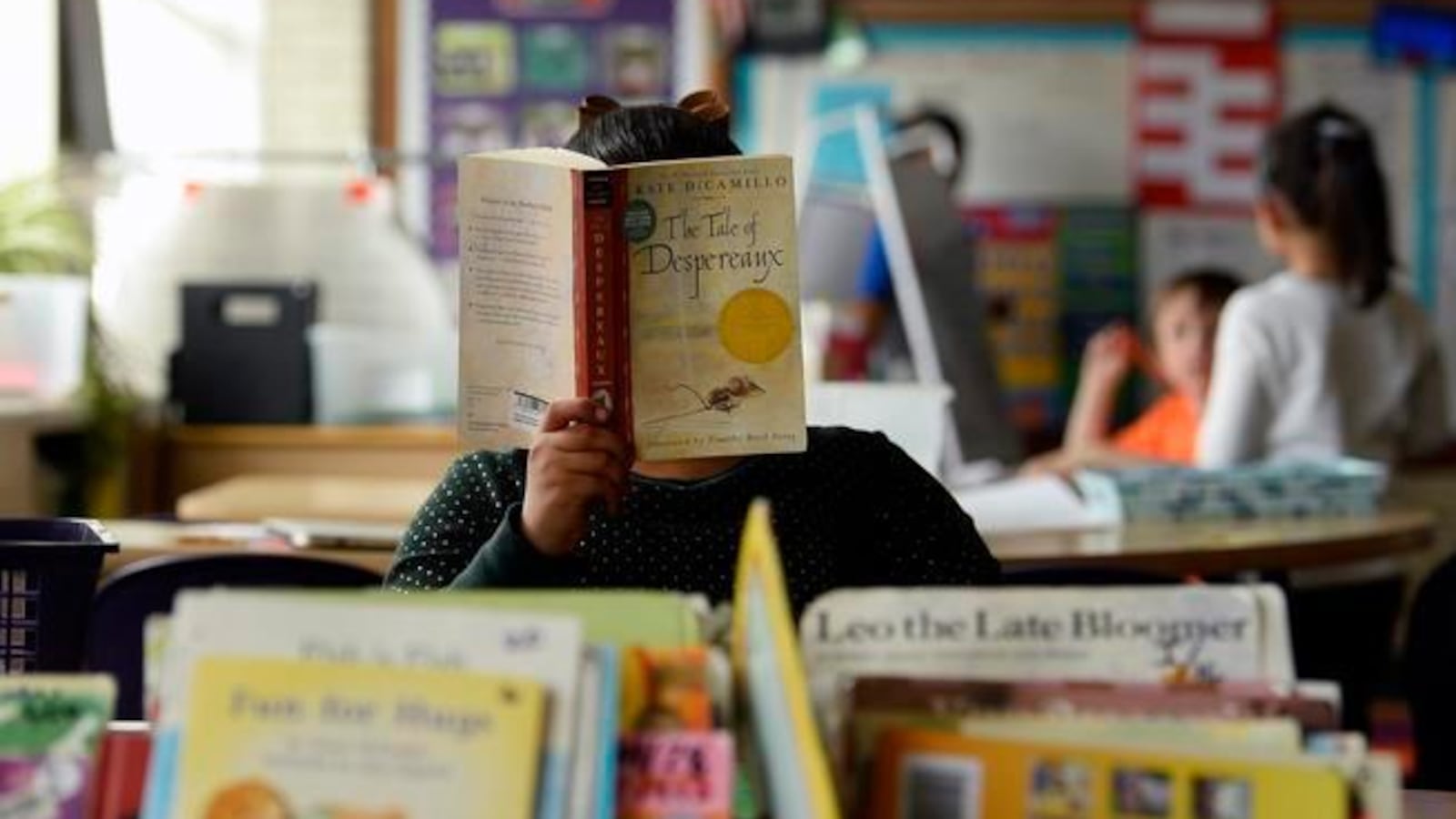

Nearly 20 years ago, as school districts across the nation were grappling with how to best build student reading skills, Florida was one of the first states to pass a law holding back third-grade students who did not read on grade level.

As the Sunshine state’s reading scores improved, more states followed suit, usually relying on one reading test to determine if a student would be promoted.

That retention strategy has now come to Memphis through a Shelby County Schools policy that will take effect during the 2021-22 school year. Test scores show the district’s youngest learners are lagging in reading, even when compared with other urban school systems. District officials say retention is necessary because without strong reading skills in third grade, students are four times more likely to drop out of high school.

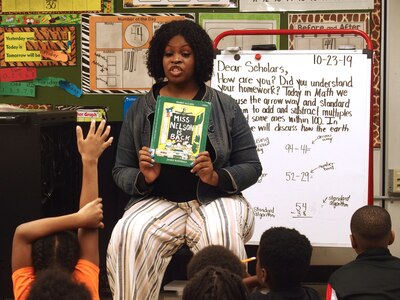

But there are key differences between the Florida law and the Memphis policy approved earlier this year because of a top official who spent two years in one of Florida’s lowest performing districts. Antonio Burt, the district’s chief academic officer, liked the “laser-like focus” on reading the Florida retention law spurred in elementary schools.

“They knew where those kids were. They were tracking all year because no one wanted to be the school or the classroom that retained a lot of students,” said Burt, who left Florida and returned to Memphis in 2017 to lead the district’s Innovation Zone before being promoted to chief academic officer last year.

But he wanted a broader approach to determine if a student would be retained and wanted to focus on students a year earlier — in second grade instead of waiting until third grade.

“I knew we couldn’t focus like a lot of states do where that policy or statute is based on third grade because that’s too late,” he said. In addition, relying on a single test to determine a promotion would create “heightened anxiety” and may not truly capture a student’s reading ability, he said.

About half of U.S. states, plus Washington, D.C., require or encourage districts to retain third-grade students who lag behind in reading, according to the federal Education Commission of States.

This is the first year Michigan plans to to hold back third-graders who score more than a grade level behind on a state reading test. Alabama passed a similar law earlier this year that will take effect the same year as the Memphis policy in 2021. Current Tennessee law also allows schools to retain struggling readers in third grade, though in practice few are held back.

Studies have shown that retention, when coupled with summer school and other student support, can have a positive effect on achievement, especially in the early grades.

When looking at local data, Burt said he and his team noticed first-grade students tend to regress around winter break because the state requirements for learning foundational reading skills are assuming a level of mastery those students have not achieved yet. That worsens going into the summer, when many students forget some of what they learned because they have limited access to enrichment programs while they’re out of school.

That phenomenon, known as “summer slide,” is worse for students living in poverty — and Memphis has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation. The backslide leading into second grade places more of a burden on teachers trying to keep up with state requirements, which have mostly moved on from foundational skills, Burt said. In addition to helping about 8,700 students continue to build those skills, teachers are trying to keep pace with grade level learning.

“We can’t let up in second grade,” Burt said. “Not every district deals with the same challenges that Memphis deals with,” such as having a greater number of students moving more frequently from school to school and having more students with limited access to early childhood education.

The year Florida’s state retention law took effect during the 2003-04 school year, districts held back about 14% of third-grade students or about 23,000 students, up from 3% the year before. If a similar situation played out in Memphis, about 1,200 second grade students would be held back. (District officials did not provide Chalkbeat with recent retention rates for second-graders.)

Over time, the share of Florida’s students retained steadily fell. Six years later, it was down to about 6%, mostly because “more third-grade students were meeting the promotion standard,” said Martin West, a Harvard Graduate School of Education professor. He and other researchers followed 75,000 students retained under the Florida law and compared them with students near the cutoff score who were promoted as well as the new students now in their same grade.

“The retention policy was one part of a much broader effort to improve instruction in the early grades that seemed to have some clear benefits for Florida students,” such as higher test scores in high school and students taking fewer remedial courses, he said. Ultimately, though, West’s research found retention had no effect on their probability of graduating high school.

The Memphis retention policy is the most debated part of the district’s strategy to improve reading, but is not its only tactic. Shelby County Schools added 56 second-grade teaching assistants in struggling elementary schools and a new phonics curriculum this year. Elementary students also have 45 minutes of instruction per day dedicated to improving reading skills.

The policy requires students to meet eight of 12 criteria, including passing grades and scores on report cards and various tests administered throughout the year. Students also will be given the opportunity to attend summer school, and they will have 45 days into the next school year to meet the necessary criteria to move to the third grade.

Chalkbeat explains: Memphis kindergarten students will be the first affected by a new retention policy in second grade. Here’s how it works.

The Memphis policy also allows for some student exemptions. Florida’s exemptions meant districts retained only about half of those who did not pass the reading test.

When Florida parents appealed a decision to hold back their child, the mother’s education level often predicted whether or not the school would promote the student, research has shown.

If a student’s mother had a bachelor’s degree, the student was 14% less likely to be retained than a student whose mother dropped out of high school — even if their test scores were the same. The study also found black students and students whose mothers were foreign-born also were more likely than their peers to be held back. In New York City, black students were more than twice as likely to be retained as white students with similar test scores.

Christina LiCalsi, who authored the Florida study, said she attributes the differences to exemptions being subjective, parents with less education not being as comfortable navigating education bureaucracy, and implicit bias from school leaders.

“Schools need to be aware of the fact that different parents have different agency,” she said. “So they need to be thinking about which students are being retained and which students are being promoted [and] whether or not there’s an equitable breakdown.”

Memphis parents like Christopher Martin, who has a son in kindergarten — part of the first class affected by the new policy — said he supports retention. But he worries about “discouragement” setting in for students who may be excelling in other subjects. He said his oldest son in fourth grade is a slow reader, but eventually gets it.

“Kids thinking, ‘What’s the point of going and doing good in everything else but this one thing is holding me back?’” he said as his son attended kindergarten on the first day of school at Delano Optional Elementary.

But Martin said he still thinks retention may be necessary for some students. “Some people make it to high school and can’t read good. Then, you got to hurt some people’s feelings when they think they’re doing good but then they fail a reading test and then get held back,” he said. “It’s got its ups and downs.”

This article tackles a topic raised during our 2019 Listening Tour. Read more about the Listening Tour here, and see more articles inspired by community input here.