Before a global pandemic closed Memphis schools indefinitely, Shelby County Schools was already planning staff cuts in its central office and in schools.

As of Saturday, Superintendent Joris Ray’s administration was expecting to eliminate 139 central office positions and 115 teacher positions, according to budget documents Chalkbeat obtained. Anticipated teacher raises would be 1% after state funding cuts last week. Overall spending for the $1 billion budget would be down $11.5 million, or about 1%.

Now as the new coronavirus spreads, the proposed 2020-21 budget is constantly changing as federal, state, and local governments adjust their spending plans for education.

“COVID has uncovered the many challenges we know large urban districts have: food insecurities, the digital divide, transportation issues,” said board member Kevin Woods. “We know that COVID-19 will make an already challenging budget even more challenging.”

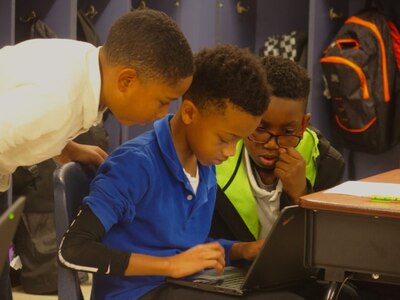

Still, at every level of government, one topic has risen to the top of budget conversations: how to help families who don’t have laptops or internet access as online instruction becomes imperative for students to continue learning while school is out.

Without immediate and long-term solutions, education leaders worry that already low test scores will worsen as schools remain closed.

“This is the perfect time for the community at large to wrap its arms around our school system,” said Cedrick Gray, the Shelby County mayor’s education liaison for the area’s eight districts. “If our students aren’t engaged instructionally, we could have incredible gaps just like we do with summer learning loss — but it will be exponentially greater.”

Last week, Ray said the public health crisis had “amplified the need for additional funding and investments” to provide laptops and internet access for the district’s students, most of whom live in poverty. The district only has 30,000 to 40,000 take-home devices for 95,000 students, and Memphis had the nation’s second lowest share of households with internet access among large cities in 2017.

Gray estimates new laptops would cost about $700 per student, while refurbished laptops could cost up to $500. Those estimates do not include the millions it would likely take to purchase an online system to track student learning and train teachers how to use it.

Shante Avant, the school board’s budget committee co-chair, said Ray’s administration is working “day and night” to provide estimates on just how much it would cost to get all students doing classwork online from home and expects specifics next week. So far, educational material provided to families on paper, online, and on TV are providing lessons, but are not meant to fully replace classroom instruction.

“We’re feeling our way … The first phase was making sure our community is safe and healthy, which means we had to close schools,” Avant said. “Now we’re moving into phase two where we have to figure out the academic and distance learning piece … We’ve got to figure out the best way where there’s equity.”

Congress just approved billions of dollars for school responses to COVID-19 including purchasing equipment for online learning and cleaning buildings, but it’s too early to know how much money Memphis will receive.

And county officials, who provide local funding for schools, are researching what it would cost to get virtual classrooms fully functioning while also calculating an expected decline in sales tax money as households spend less on businesses that had to close or cut back operations during the pandemic. State officials rely on sales tax money for schools and are anticipating a significant drop in revenue.

“This is going to force us to be disciplined about what we invest in,” said Michael Whaley, who leads the county commission’s education committee. He added poverty should not be the reason students do not have access to online learning. “That’s just not fair to those students. I think this lights a fire to figure out how to do this.”

Superintendents across the state are worried the expected economic downturn could reduce education spending in the long run, said Dale Lynch, the executive director of the Tennessee Organization of School Superintendents.

“Right now, we’re focused on a health crisis. But we’re also in an economic crisis, and we don’t know yet what that is going to mean for schools,” he said.

Funding is down under a recently approved barebones emergency budget, including money for teacher raises and other initiatives. Gov. Bill Lee has not yet earmarked money for districts to purchase equipment to launch online classes, so only districts that already had enough laptops for every student are fully switching to digital learning.

In New Jersey, the state legislature passed a series of emergency bills in response to COVID-19, including a grant for school districts to purchase technology including laptops, tablets, and internet hotspots for students in need. In Chicago, the school board recently approved up to $75 million for emergency response services, including computers and iPads, but warned the investment would prompt difficult budget cuts down the road.

Unlike previous years, Shelby County Schools cannot lean on its reserve fund to cover shortages. The district’s reserve fund contains about a month’s worth of operating costs, or $83 million, after years of county officials and school board members urging district staff to spend it down and pump money into the classroom. Just five years ago, the district’s reserve was at $110 million.

For next school year, the district plans to only use $5 million of its reserves, down from $32 million last year to keep a minimum 8% of its annual budget in reserves, as required by board policy.

The district plans to cut $25 million from its central office by eliminating jobs and spending less on contracted services, such as consultants. Of the 139 positions the district plans to cut, more than half are maintenance technicians and school-based campus monitors for cafeterias, hallways, study hall, and in-school suspension.

Of the 115 teacher positions the district proposes to cut, a third are related to planned school consolidations such as the new Alcy Elementary School, which will combine Alcy, Charjean, and Magnolia elementary schools into a new building. The district struggles to fill teaching positions every year, so it’s unclear if the proposal includes eliminating unfilled positions or existing teachers. Shelby County Schools did not immediately respond to Chalkbeat’s request for comment Thursday.

In the meantime, community meetings to go over the district’s budget priorities are postponed because the city is under a stay-at-home order that prohibits “non-essential” travel. The school board is working on conducting virtual meetings and expects to hold a budget committee meeting at 3 p.m. Monday.

But no matter how long school is out because of the new coronavirus, state law requires that local governments that fund education approve a spending plan for the 2020-21 school year by July 1, a little over three months from now.

Chalkbeat reporter Marta W. Aldrich contributed to this story.