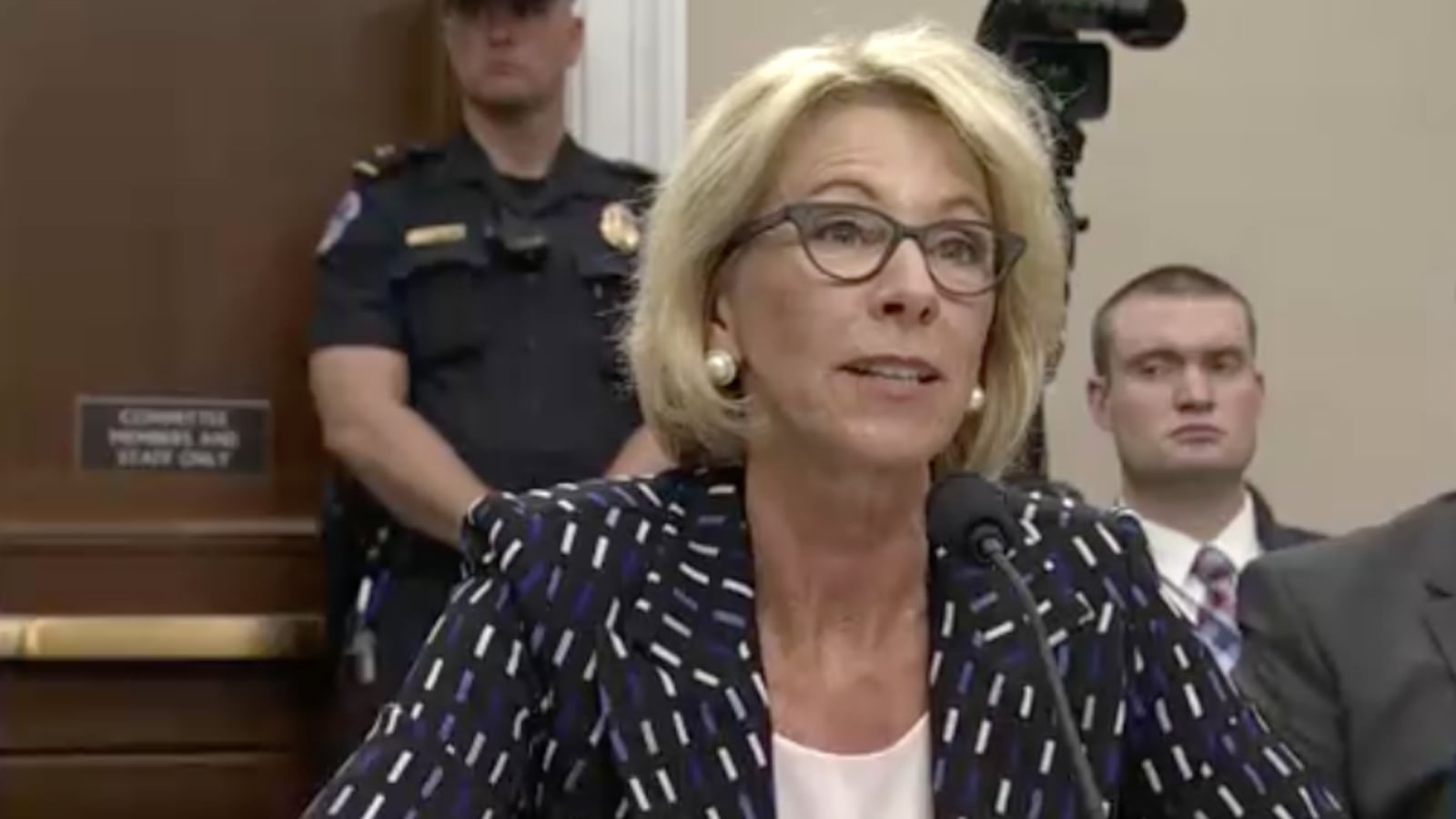

Betsy DeVos faced tough questions Wednesday from lawmakers on whether private schools in voucher programs would be allowed to exclude students, including LGBT students and students with disabilities.

The budget plan the Trump administration released this week asks for $250 million to fund pilot programs that would use public funds to pay tuition for students at private schools. Those voucher programs are a focus of U.S. Education Secretary DeVos, who has said they are critical for helping low-income families who need more good choices for educating their children.

The budget is unlikely to be enacted by Congress, but it’s put more attention on a key aspect of how these voucher programs work: outside of the public school system and without the same rules for accountability and access.

Rep. Katherine Clark, a Massachusetts Democrat, asked DeVos about a Christian school in Indiana that participates in that state’s voucher program and whose handbook says students may be denied admission if they have a gay family member.

“If Indiana applies for this federal funding, would you stand up that this school be open to all students?” Clark asked. “Is there a line for you on state flexibility?”

“For states that have programs that allow parents to make choices, they set up the rules around that,” DeVos responded.

“So that’s a no,” Clark said.

DeVos noted that the education department’s Office of Civil Rights would continue its work. All private schools are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race or national origin, but they can discriminate based on sexual orientation — in fact, no voucher program in the country prohibits participating schools from discriminating against LGBT students.

Private schools may also be able to deny admission to students with disabilities. DeVos herself visited Providence Cristo Rey High School in Indianapolis on Tuesday, a Catholic school that participates in Indiana’s voucher program and whose admissions website warns that it has “limited ability to offer services” for students with disabilities.

Some voucher programs are designed specifically for those students. In turn, those students typically give up some or all of their rights under IDEA.

Rep. Mark Pocan, a Wisconsin Democrat, challenged DeVos on whether new voucher programs would actually help needy students with few options. In Milwaukee, home to the country’s longest-running voucher program, Pocan noted that many voucher recipients already attended a private school and came from wealthy families.

“The 28,000 students that are attending school by the choice of their parents in Milwaukee — that is a success for those students,” DeVos responded. “Those parents have decided that’s the right place for their children to be.”

Pocan mentioned recent studies out of Indiana, Louisiana, Ohio, and Washington, D.C. showing that students using vouchers lose ground on standardized tests after attending private schools. (“I think you were asked recently about this and I know you were on your way out and didn’t have a chance to answer, so I’m glad that today we’ve got a chance to ask some of these questions,” he said.)

Pocan said his experience had led him to conclude that Wisconsin’s school voucher programs had failed. However, research on Milwaukee’s voucher program found it has had a positive effect on students’ likelihood of attending and staying in college.

Pocan also asked DeVos about how any new voucher programs that used federal dollars would be held accountable for their success. DeVos responded by discussing the responsibility of each state to craft accountability rules under ESSA, the new federal education law, which private schools are generally not subject to.