Look around an average charter school. The difference may be too small to be perceptible, but you might notice a few more girls than boys.

That is the provocative finding of a study released late last year examining data from charter schools across the country, with a focus on North Carolina and the KIPP network of charter schools. The results re-open the long-standing debate on whether charter schools exclude or push out certain types of students.

“The efficacy … of charter schools cannot be fully understood without attention to how students and families sort into schools,” the study’s authors write.

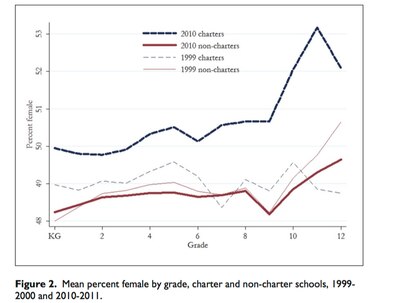

The latest research, conducted by Sean Corcoran and Jennifer Jennings, both of NYU, and published in the peer-reviewed journal Educational Policy, examines national trends. As of the 2010–11 school year, 50.7 percent of charter school students were girls, compared to 48.8 percent of students in traditional public schools — a small but notable gap.

This gap is larger in later grades, and it has grown as the charter sector has expanded over time.

The findings are backed up by more recent data: in the 2014–15 school year, 50.4 percent of students at charter schools were female, compared to 48.5 percent in district schools.

The researchers also look specifically at KIPP schools, which lead to large test score gains, according to past research. The study shows that KIPP schools had an even larger gender gap than other charters, serving about 3 percent more girls than similar district schools.

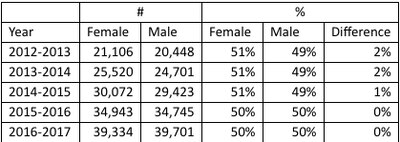

Steve Mancini, KIPP’s public affairs director, said the network has worked to address this and provided more recent data to Chalkbeat showing that the organization’s schools now enroll roughly the same number of boys as girls.

Tracy McDaniel, the founding school director of a KIPP school in Oklahoma City, said his school had reduced the gender enrollment gap by focusing on reducing school suspensions, which disproportionately fall on boys.

“The parents were complaining about suspensions, and boys got in more trouble than the girls,” he said. “We felt like that was a contributing factor if the parents pull out the kids, [and] they were pulling out more boys than girls.”

McDaniel said that his school had gone from roughly 45 percent boys to 50 percent.

However, even a 50–50 split is different than the average traditional U.S. public school, which enrolled 3 percent more male than female students in the 2014–15 school year.

This is not the first time the charter–district gender gap has been noted, but the NYU study appears to be unique in making the question its main focus.

The reason for the gap is unclear.

Corcoran and Jennings point out that girls are disciplined less than boys, and thus might do better in schools with rigid environments. So-called “no excuses” charter schools have been criticized for strict disciplinary practices and high suspension rates; some charter advocates and operators, including KIPP, have said that they are working to reduce exclusionary discipline.

Other hypotheses include different curriculum or programs at charter schools that appeal to girls, a potential lack of services for special education students (who are disproportionately male), and parental preferences for smaller schools for girls.

The gender gap might help explain differences in performance between district and charter schools. Sophisticated research on the effects of charter schools controls for individual student characteristics, including gender, but Corcoran and Jennings point out that this might not account for peer effects — the potential for other students to influence their peers’ performance.

“Given what is known about the positive peer effects of girls for both boys and girls, the success of charter schools may be due at least in part to the gender balance in these schools,” the authors write.

“Although the gender gaps estimated here are not large enough to explain documented differences in charter and traditional school performance, they are meaningful in size.”

This gets at the heart of the debate on charter schools, and if their high test scores in some places — like Boston, Denver, New York City and other urban areas — may be a result of the students they teach rather than how well they teach.

Existing studies on this question paint a complicated picture of how charter schools differ in the students who enter, stay, and leave.

In KIPP specifically, a 2016 study found that student attrition is comparable to other nearby schools, but new KIPP students are more likely to be girls and have higher prior test scores than entering students in traditional public schools. The research estimates that peer effects are likely to explain only a small share of KIPP’s test score gains.