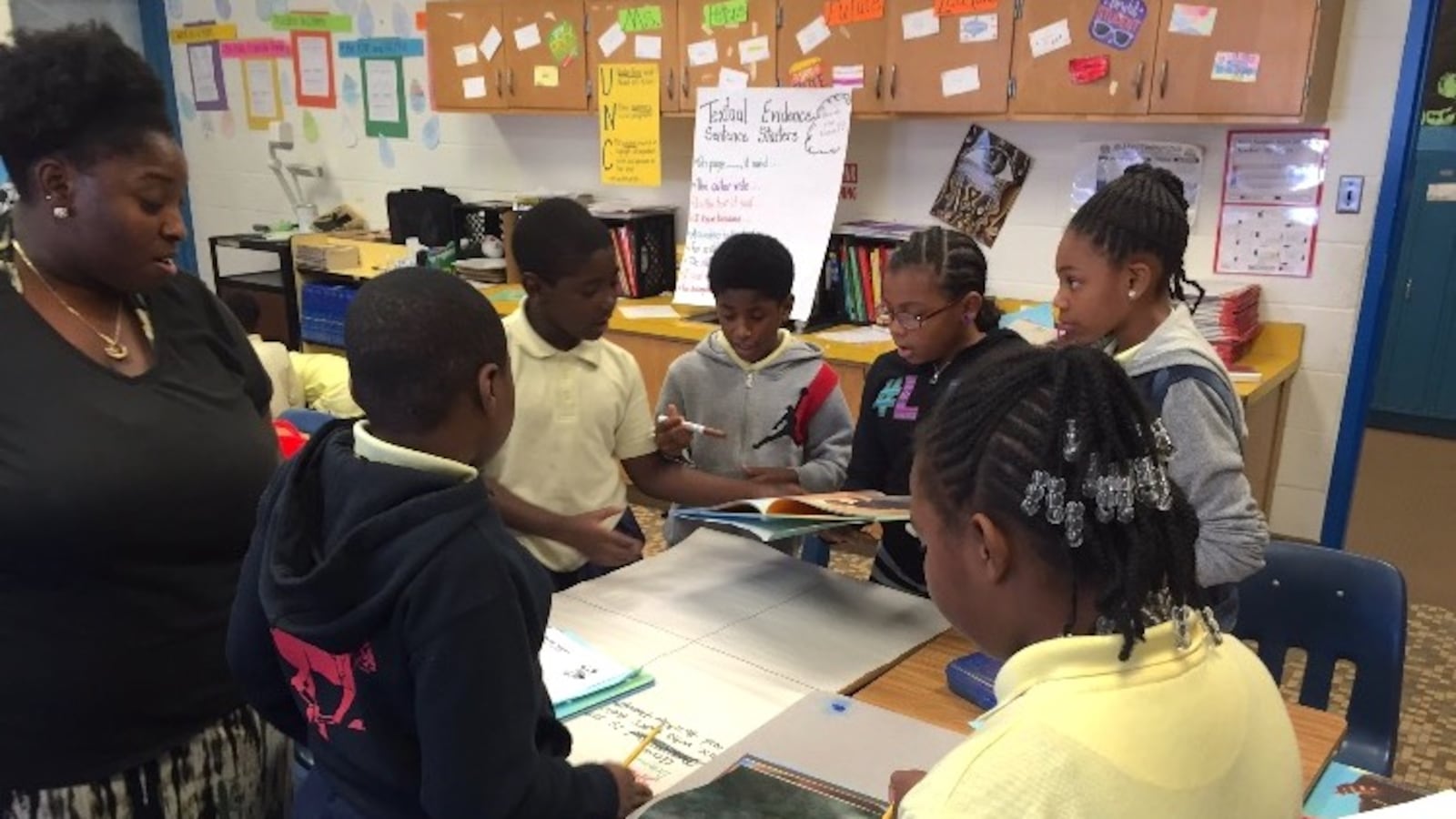

In her first year teaching fourth grade in Baltimore, Tamika Peters earned the highest rating possible on her official evaluation.

Peters brought a deep well of experience to her work: over a decade at her school as a long-term substitute and paraprofessional. More recently, she had earned a master’s degree in education and completed the Baltimore City Teacher Residency training.

Peters, now in her second year teaching, is also at risk of being kicked out of the classroom.

The hang-up: a math exam she has taken and failed four times. If she doesn’t pass it by the end of this school year, she will have to leave the job she loves.

“I don’t want to lose my career,” she said. “I wish there was a way that that didn’t determine who I was as a teacher or as a person.”

The certification rules that might halt Peters’ career have high stakes both for individuals like her and for the states that have bet on improving education by “raising the bar” for entering teaching — increasing GPA requirements and adding tests in a bid to make the profession more prestigious and attract top talent.

Because candidates of color are less likely to get over the certification hurdles, the policy risks excluding teachers of color, like Peters, even as there has been heightened attention on the lack of diversity in the teaching profession.

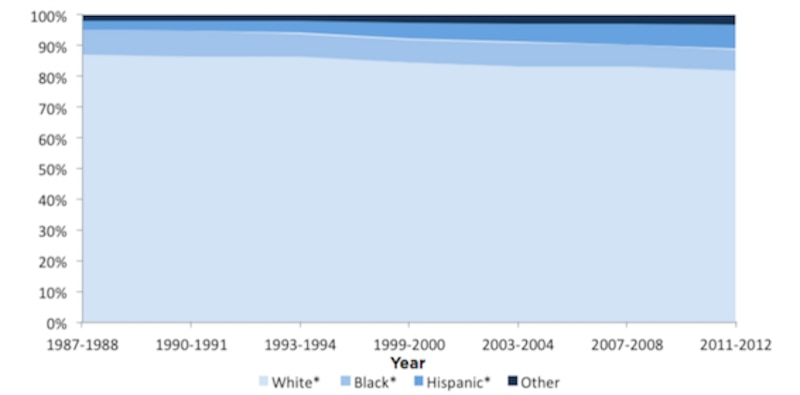

Nationally, less than 7 percent of teachers are black, a share that’s actually fallen since the federal government started tracking that 30 years ago. Maryland, for one, has a declared a “shortage” of minority teachers.

But to some, the approach helps ensure kids of color have equal access to qualified teachers, including those with a strong knowledge base.

“Individual stories make bad policy,” said David Steiner, a professor at Johns Hopkins and a member of the Maryland State Board of Education. “Policies by definition draw lines.”

“What’s racist is the way we put the least well prepared teachers in the classrooms of our most disadvantaged students,” he said.

A costly, challenging certification process

Peters, who is 38, began working as a substitute teacher 13 years ago at an elementary school in west Baltimore, the city where she spent most of her childhood. She often took over for teachers for extended periods; over time, she took on a number of different roles at the school.

“I loved it,” she said. “It was never about titles for me. It was more like I was in a school working with kids, made a difference, and my strengths allowed me to do a lot of different positions in the buildings.”

After a while, Peters’ principal pushed her to become fully certified so she could have her own classroom. She initially hesitated, but her boss persisted. Eventually, she agreed.

That’s when she hit the first roadblock. Her college grade-point average from over a decade earlier was one-tenth of a point below the state’s cutoff for teachers, a 2.75. So she enrolled in a master’s degree program, which allowed her to take additional classes and boost her GPA.

From there, she enrolled in the Baltimore City Teacher Residency, which trains aspiring teachers over the summer.

Both programs, Peters said, were of only marginal help to her as a teacher, particularly as someone who had been working at a school for so long. They also came with hefty price tags. She went into debt to pay for the master’s program; the residency cost about $6,000, and required taking on an intensive, unpaid workload over the summer.

That gave Peters an initial teaching certification, valid for two years. But to keep teaching her own class, she needs to successfully complete the battery of standardized tests Maryland requires of teachers. If she doesn’t, she can only teach as a substitute, which would put her back where she started.

Peters quickly passed three Praxis exams in reading, writing, and elementary education, but she struggled with math. The first time she took the math test, she failed by a large margin, though more recently she fell short by just eight points. She is now preparing to try for the fifth time.

“These eight points are scaring me senseless,” she said. “I’m studying every chance I get. It’s kind of difficult when you’re focused on doing things and you’ve got life and you have this nervous energy about taking this test.”

Meanwhile, the costs of the exams have accrued. Each additional math test costs $90; she’s now shelled out hundreds of dollars on the required assessments.

Measuring a teacher’s value

The goal of the certification tests and rules is to screen out teachers who aren’t likely to succeed on the job. But is performance on the exam a good indicator of how Peters — or any other teacher — performs in the classroom?

Peters argues that it’s not.

“In this profession, I don’t think you can judge a person by what paper says,” said Peters, who got high marks on her first-year teacher evaluation. “You actually [have] got to see a person doing it.”

Andy Smarick, the president of the Maryland Board of Education, said he couldn’t comment on specific cases, but that the issue highlights an important tension.

“What that scenario forces policymakers to do is ask what is going on here: Is there something wrong with the evaluation system or the certification system? Because it could be either,” he said.

Peters said the Praxis exam emphasizes algebra and geometry concepts that are not integral for her fourth-grade teaching, which focuses on place value, arithmetic, fractions, and how to use a ruler.

Steiner, though, said that requiring teachers to have a level of broad knowledge makes sense. “It’s reasonable to ask that a teacher know more than her students, otherwise she can’t understand their mistakes,” he said.

Peters says being a black teacher of predominantly black students matters, too.

“The Freddie Gray riots literally started less than a four-minute drive from where I teach,” she said. “When my kids come in and they want answers or they have questions … I can give them the heart of the answer because I’ve lived in the city.”

Research backs Peters up to some extent. Studies have found that black students in particular benefit in a variety of ways from having a black teacher, leading to better test scores, more positive views of school, fewer suspensions and expulsions, more referrals to gifted classes, and lower dropout rates. Black teachers, research has found, also have higher academic expectations for black students than other teachers.

At the same time, research has generally shown a positive but modest link between someone’s scores on standardized exams and their effectiveness as a teacher — but these exams may be less predictive for teachers of color. A study looking at Praxis scores in North Carolina found that black students performed better with a black teacher who had failed the exam than with a white teacher who passed the test.

America’s teaching force, by race

Weighing competing factors

Steiner agrees that teacher diversity is critical.

“We know that all else being equal, minority students … do respond to teachers who share their ethnic background,” he said.

But Steiner argues that general cognitive ability is associated with teacher performance, and students of color shouldn’t be taught by teachers with the lowest academic skills.

“There’s a vicious circle here,” he said. “We need to break the cycle of the worst-prepared teachers teaching our most-needy students.”

Still, Steiner says, nothing — including a teacher’s test scores — is a guarantee of performance. Much of what makes an effective teacher is hard to see before someone reaches a classroom.

He imagines an extensive redesign of teacher training to more closely resemble systems in other countries, like Finland, that perform well on international tests.

“We’ve got to redo the whole teacher pipeline: effective preparation, effective induction, real career ladders, an attractive profession that can have serious challenges to entry, as top professions do,” said Steiner, who noted he recently joined the Maryland school board and wants to address the issue in the future.

Peters, for her part, said she has seen a number of effective teachers of color lose their jobs because of the certification exams. She’s also watched teachers with high test scores struggle in the classroom.

“There was a lady in my [residency program] who bragged about her test,” Peters said. “She didn’t last in Baltimore city [schools] through January.”

Peters is going to keep taking the math test until — she hopes — she passes it. But the process has been demoralizing.

“I get discouraged, I do,” she said. “I’m not a dummy.”