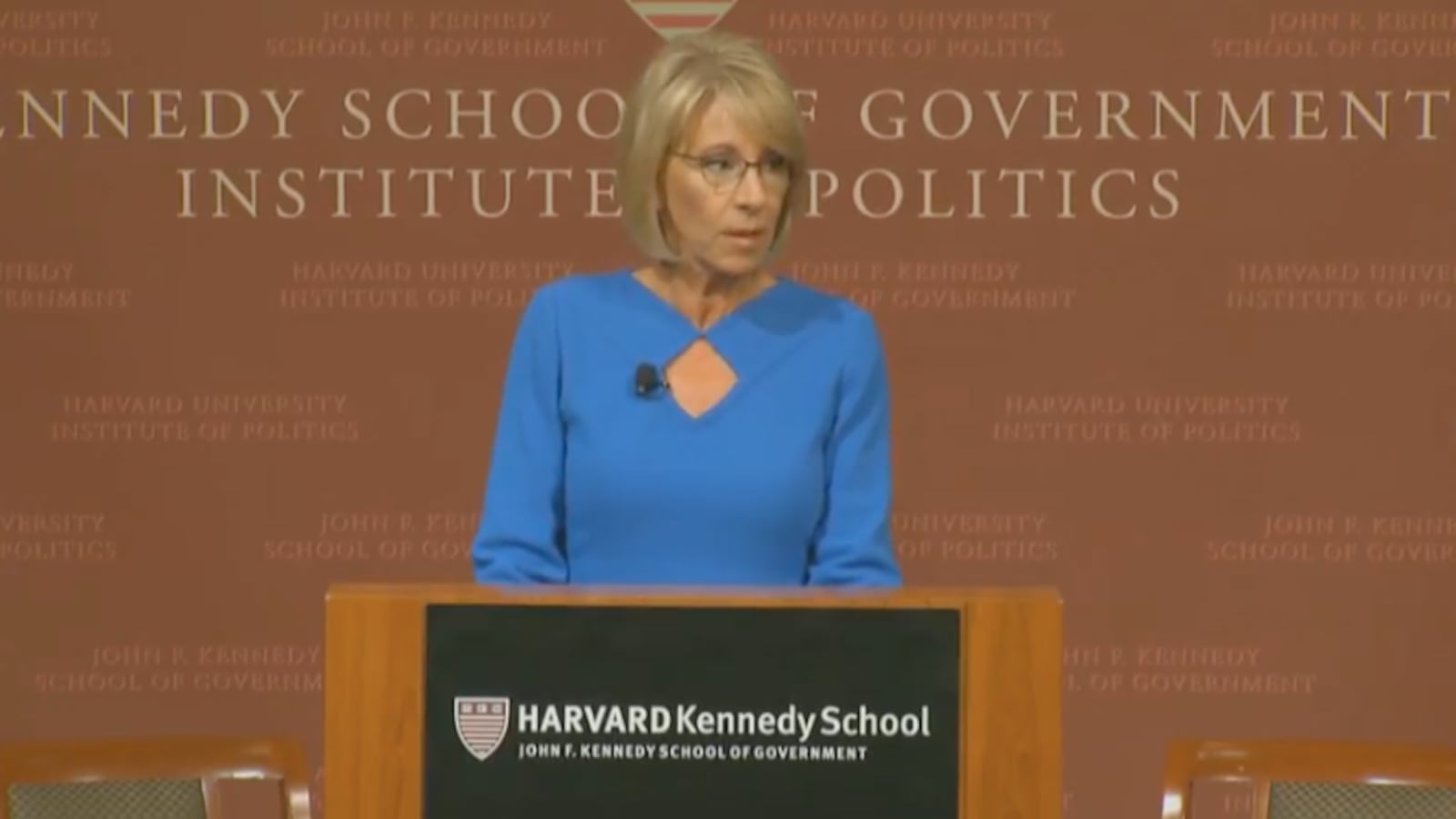

By now, U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos must be used to a tough audience. Her reception at Harvard Thursday, featuring plenty of protesters, was no exception — in line with what she’s faced at Senate confirmation hearings and at school visits across the country.

DeVos was attending a school choice conference filled with supporters of her perspective, and she was questioned by Harvard Professor Paul Peterson, who has long advocated for private school vouchers. But she was also met a number of skeptical audience questions.

Here were some highlights from the night:

1. DeVos has a new analogy: schools are like restaurants and food trucks.

The education secretary has compared schools to taxis and Blockbuster to emphasize the need for innovation. We need schools operating like Uber and Netflix, she’s urged.

On Thursday, she offered a new metaphor for school choice — one that tried to deflect criticisms that she is anti-public education.

“Near the Department of Education, there aren’t many restaurants. But you know what — food trucks started lining the streets to provide options,” DeVos said. “Some are better than others, and some are even local restaurants that have added food trucks to their businesses to better meet their customers’ needs.”

“Now, if you visit one of those food trucks instead of a restaurant, do you hate restaurants? Or are you trying to put grocery stores out of business?” she asked. “No. You are simply making the right choice for you based on your individual needs at the time.”

This gets at the heart of the school choice debate — whether or not schools should function like consumer goods in a marketplace.

2. Eight months on the job hasn’t changed her view that the feds should play a minimal role in deciding how schools are run or which schools are working.

The first question lobbed at DeVos came from a parent who has sent her children to district, charter and parochial schools, but argued that “as a whole, most [school] systems … aren’t working for black parents like me.”

The question focused on DeVos and the federal government’s role in ensuring quality schools: “Why don’t you think that you should have any say or any control over setting minimums … so systems aren’t the wild, wild West?”

DeVos, a skeptic of the federal role in education, immediately pivoted back to school choice. “My goal, my hope, is that all parents like you and all others would have the power to choose a school that is right for your child,” she said. “Accompanying that there has to be a lot of great information available to parents.”

DeVos also demurred when Peterson asked her a nitty-gritty question on ESSA, the federal accountability law. Peterson noted that many states — whose plans have been approved by DeVos’s education department — have decided to judge schools, in part, by rates of student chronic absenteeism. DeVos wouldn’t say what she thought of this.

“All the states are coming up with different measures,” she said. “I’m not sure that that’s the right approach or the best approach, but I’ll withhold judgment, and let’s see what the states’ results are.”

3. She’s still on the defensive when it comes to Michigan’s charter schools.

One questioner, who — like DeVos — is from Michigan, echoed a common criticism of the secretary: “Thanks in part to your advocacy, we [Michigan] lead the nation in for-profit schools, paired with some of the weakest accountability laws. … Given the fact that in Michigan students have a lot of choice, but not good choices, and corporations are profiting from that, why do you think that choice is appropriate for the nation?”

DeVos responded, “Of the students that are still left in the city of Detroit, 49 percent of them” — here, the audience reacted with guffaws and boos, and DeVos interrupted herself. “Excuse me, everybody who has had means and wants to move elsewhere has moved outside the city of Detroit. And the students that are there, 49 percent of them have chosen to go to charter schools. Nobody is forcing them to go to charter schools.”

“Of the traditional public schools in Detroit,” she continued, “not one of them has ever been closed down because of performance, not one. Yet there have been over 20 charter schools closed. … The reality is, of kids going to charter schools in Michigan and in the city of Detroit, they are gaining three or four months per year over their public school counterparts.”

DeVos appears to be referencing the CREDO study of Michigan charters, which shows that charter students outscore similar kids in public schools on standardized tests.

It’s also worth noting that while it may be true that no Detroit district schools have been closed explicitly for performance, well over 100 Detroit district schools have shut down since 2000, presumably due to declining enrollment. And another study from CREDO found that low-achieving district schools in Michigan were more likely to close than low-achieving charters.

4. Research undermines DeVos’s claims on school choice and school spending.

In her speech, DeVos hit on what she believes works (school choice) and what she thinks doesn’t work (spending more money).

She pointed to a study released Wednesday on Florida’s tax-credit voucher program, saying that it “demonstrated the longer a student participated in the choice program, the better their long-term educational outcomes.”

Later, she said, “More funding? Does that fix the problem? Again, the data would show otherwise, with the U.S. spending significantly more per pupil than nearly every other country in the developed world – and without the student achievement to go along with it.”

The research on voucher programs is more mixed than she suggests. It also may be misleading to say that students who stay in private school through Florida’s program longer, benefit more; as the researchers acknowledge, this may have less to do with the program and more to do with the types of students who stick around.

On funding, DeVos’s claim is also difficult to support. Recent research shows that schools and students do in fact benefit from additional resources. DeVos is right that in raw dollars per student, the U.S. outspends most other countries. As a percentage of GDP, though, our spending on K-12 education is about average.

5. DeVos is excited about tax credits, but federal action isn’t imminent

The education secretary reiterated that she’s interested in a tax credit program that would help parents send their students to private school — but that she had no plans to make any announcements.

“Not here and not now,” DeVos said. “There’s certainly a lot of hope for that.”

“I would just hope that more states would embrace this notion and the ones that actually have it would expand their offering and get even more assertive about offering parents more of these choices,” she added.

Eighteen states have already adopted those policies, which allow individuals to donate to nonprofits, then get a tax cut for amount they donated. The donated money is doled out as tuition stipends, which function just like school vouchers.

Congressional Republicans’ new proposal to overhaul to federal tax policy, unveiled Wednesday, didn’t touch school choice.

6. She stayed calm as audience members unfurled protest banners and students asked pointed questions about her wealth and her department’s Title IX changes.

Outside the event, protesters took up about a city block in front of the Harvard Kennedy School. Speakers included presidents of Boston Teachers Union and the New England NAACP, plus Boston mayoral candidate Tito Jackson. The crowds sang “When the Schools Belong to Us” to the tune of “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

Inside, one student asked, “How much do you expect your net worth to increase as a result of your policy choices?” to laughs and snaps.

“I’ve been involved with education choice for 30 years,” she responded. “I have written lots of checks to support giving parents and kids options to choose a school of their choice. The balance on my income has gone very much the other way and will continue to do so.”

Grace Tatter contributed reporting.