Most of what we know about the effectiveness of charter schools has come from scrutinizing testing data. That’s frustrated some who see the focus on test scores as too narrow. Now, a major study recently released by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research joins a growing body of research that moves beyond tests to judge charters.

This analysis focuses on charter high schools in Chicago, which now educate over a fifth of Chicago high school students. The main takeaways: charter schools seem to help students in the short- and long-run, but those schools also have higher student turnover.

“Test scores are important, but so are other things,” said Julia Gwynne, one of the study’s authors.

The study’s findings will provide grist for both supporters and critics of charter schools. It also offers a number of important takeaways for national charter school observers.

The study shows that one of the larger charter high school sectors in the country is having big positive effects on students.

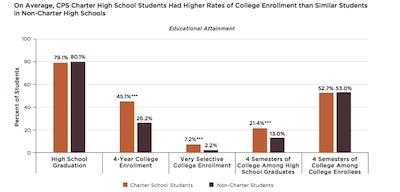

Attending a charter high school in Chicago led to substantial improvements in test scores, high school attendance, college enrollment, and college persistence.

These effects were relatively big: charter students were in attendance about eight more days on average and scored a full point higher on the ACT (which is out of 36 points). They were nearly 20 percentage points more likely to enroll in a four-year college, and also much more likely to persist in college through four semesters.

“The college enrollment rates are quite high – I would put that at a very sizable difference,” said Gwynne.

(It’s worth pausing here to note that although charters had a big edge in getting students to college, the college persistence for both sets of students was fairly low, echoing a national trend.)

These are not just raw comparisons of performance: the authors control for a variety of factors that might affect student performance in high school, including poverty, eighth grade test scores and attendance rates, and special education status. This strongly suggests that differences between students are caused by the quality of their schools. The study largely uses data between 2010 and 2013, although the paper goes further back to assess college outcomes, focusing on students who entered high school between 2008 and 2010.

These results are consistent with another recent study showing that Noble, a large charter network in Chicago, led to a big boost in college attendance.

On one important measure charter students were on par with district kids: high school graduation rates were essentially identical.

Interestingly, the results from this study are quite similar to research on Boston’s charter schools. Students there saw big gains in test scores and four-year college enrollment, but the same or lower high school graduation rates.

It’s among the first studies to document a common criticism lobbed at charter schools: high rates of student attrition.

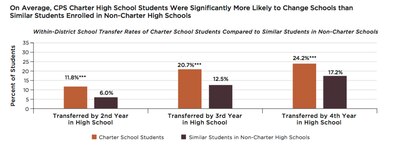

There’s a big caveat to these findings: students are much more likely to leave a charter high school than a district one.

The natural question when considering the two main findings from the study — better outcomes but higher transfer rates — is whether one causes the other. That is, do Chicago charters just get better results because only more successful kids stick around? No, at least not directly.

To measure the effects of charters, the study follows students over time. Charter schools are judged by the performance of all students who start ninth grade at a charter — even if they subsequently transfer out. This is a common technique among researchers and means that the estimated charter impacts are likely conservative.

Still, the paper adds weight to a criticism that has dogged charters across the country: that they push kids out who are struggling or who have behavior problems. There have been a number of anecdotes to support this, but previous studies in a few districts, including New York City and Denver, had generally found little evidence that students leave charters at high rates.

Generally, low-achieving students in Chicago charters were more likely to transfer out than high-achieving ones — but that pattern was also true in district schools. Charter high schools had high attrition rates among both high- and low-performing kids.

The research does not show why students were more likely to leave charter schools.

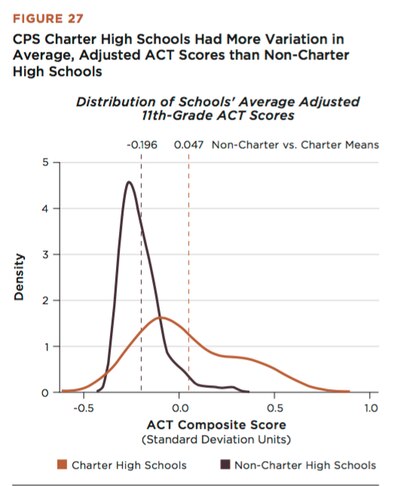

The study highlights that even in a successful charter sector, there are some really low-performing schools.

It’s often heard in the charter school debate: charter success varies significantly from school to school. This is hardly surprising; it’s true of district schools too. But the Chicago study finds that on measures like test scores and college enrollment, charters vary even more than district schools in their impact on students.

That means there are more really good charter schools, but also more bad ones, even as on average the charters are better. (There is some evidence that is true of charter schools in Arizona, North Carolina, and Texas.)

The findings suggests that policymakers should be wary of judging a school by its sector, and that they need to be especially vigilant for struggling charter schools.

The study hints at — though doesn’t definitively explain — why some charter schools are successful.

The latest research can’t show why, overall, Chicago’s charter high schools seem to be high-performing, but it can point to ways they differ from district schools.

Charter high school teachers reported a higher sense of trust and collective responsibility among colleagues. Charter students said their schools were more engaged in helping them plan for life after high school, and teachers said there were greater expectations for college attendance. The schools also had tougher requirements for moving on to the next grade and for graduating high school.

Perhaps surprisingly, charters had a similar number of school days as the district.

Charter schools may have certain advantages over district schools. For instance, charter teachers report that parents are significantly more involved in schools; this may be a reflection of how charters work with parents, but it could also be about the families who select charters (or both).

The fact that charter schools have higher transfer rates may also matter, as does the finding that those students usually end up in district schools. Other research has shown that students entering school mid-year can hurt the performance of their peers, which might be a particular challenge for Chicago’s neighborhood schools.

The study does not look at financial differences across the sectors, including the role of outside money in supporting charter schools, nor does it examine school discipline or student suspension rates.

“What our next steps should be — really understanding best practices in high-performing charter schools is probably at the top of the list,” said Gwynne, the researcher. “To really understand what’s happening on the ground, you need to send researchers into schools.”