What if an education law passed, but nobody followed it?

That appears to be the bizarre situation in Arkansas, which in 2013 enacted a straightforward law banning out-of-school suspensions for truancy.

But three years later, nearly 1,100 students were still suspended for not showing up to school. Many Arkansas schools were simply not complying with the law, according to a new study.

What happened? It’s not entirely clear, but a communication breakdown may be to blame. The study notes that schools didn’t hear explicitly from the Arkansas Department of Education about the new law until January 2017.

The state disputes this — kind of — pointing to 2014 and 2015 memos, though neither actually mentions the rule change or acceptable penalties for truancy. A department spokesperson said the memos’ “regulatory authority” include the law banning suspensions.

“While [the department] does not track every phone call or correspondence, in general we have ongoing communication with educators, schools, districts and education service cooperatives,” said the spokesperson, Kimberly Friedman.

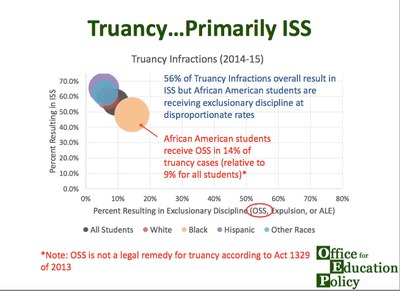

What’s clear is that only some Arkansas schools changed their practices. In the 2012-13 school year, about 14 percent of truancy cases resulted in out-of-school suspensions, and by 2015-16 that had dipped to 9 percent. It’s not clear whether that drop was due to the law.

(Notably, nearly 2 percent of truancy cases in 2015-16 resulted in corporal punishment, which remains legal in Arkansas public schools despite efforts by the federal government to eliminate the practice.)

The study, which was published last week in the peer-reviewed Peabody Journal of Education, also found that schools serving more students of color were less likely to have followed the law.

Schools with 10 percent more black students than average were about 5 percentage points less likely to eliminate suspensions for truancy. That finding underscores concerns from discipline reform advocates about the disproportionate effect suspensions have on students of color.

“The types of schools that the state was likely intending to impact … were also the types of schools that failed to comply,” researcher Kaitlin Anderson of Michigan State University wrote.

Although pointing to an outlier case, the paper highlights a key challenge of changing school discipline rules: laws and mandates are no guarantee of real change. That’s especially true if educators don’t believe in the changes, schools aren’t given the resources to change, there’s no enforcement of new guidelines — or if schools don’t know that rules have changed at all.

“You might expect [suspensions for truancy] to go down to 0 percent, but that would be if all schools knew about the law, were able to comply with the law, and wanted to comply with the law,” said Anderson.

It’s not the first study to highlight the challenges of instituting, and tracking, school discipline changes. After Philadelphia banned suspensions for certain lower-level offenses, more than three-quarters of schools did not fully comply, another recent paper found. In Washington, D.C., an investigation found that some schools simply didn’t report all out-of-school suspensions amid the district’s efforts to cut down on exclusionary discipline.

In other cases, though, policy changes are leading to fewer suspensions, at least according to official numbers. Los Angeles and New York City, for instance, have reported substantial drops in out-of-school suspensions in recent years.

In Arkansas, the back and forth over the new findings began in February 2016, when the researchers presented preliminary findings to the Arkansas State Board of Education. They reminded board members that suspensions for truancy were illegal and noted that “over 100 districts were still doing this as of 2014–15.”

Nearly a year later, in January 2017, the state commissioner of education issued a brief memo, which said that “State Board members requested the department remind districts” of the ban.

Friedman said there wasn’t data on whether schools are complying with the law this year, since schools don’t submit discipline reports to the state until June.

Arkansas now has another chance to tackle the challenge of implementing a new discipline policy. Just last year, the state passed a law prohibiting most out-of-school suspensions in in elementary school.

Anderson said that it makes sense for state leaders to engage local district and school officials more when trying to change how schools do business. “Having some of those conversations is going to be more productive in the long run rather than trying to just set a hand-offs, high-level policy,” she said.