Utah spends about $7,000 per student in its public schools, but gives much more to schools with many poor kids. New York spends more than $18,000 per student, but doesn’t give extra money to high-poverty school districts.

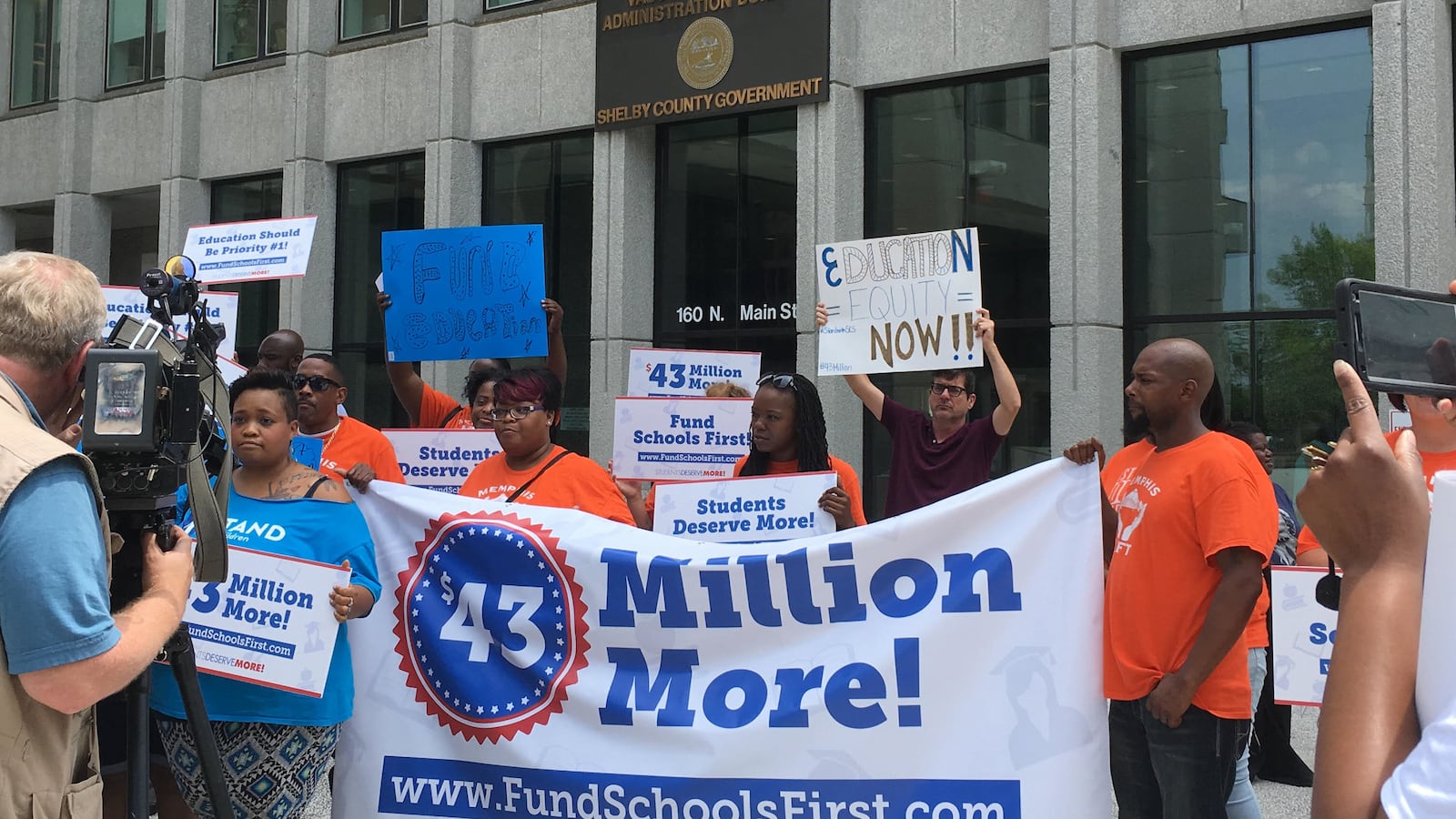

What’s the right number, and who should get the most? The questions are at the heart of many of the heated battles in public education: In Detroit, teachers have complained about buildings that are falling apart, while lawsuits from Washington to New York to Kansas have led to protracted legal fights.

It makes sense to look closely at education spending, since several recent studies link more money in schools to better outcomes for students. But describing the state of school funding in the U.S. is tricky, since schools receive a combination of local, state, and federal dollars and because disparities can exist between states, between districts, and between schools.

That’s why we combed through three recent reports from the Education Law Center, Education Trust, and the Urban Institute, which help explain how big the school funding pot is and how that money is really divvied out.

What stands out is that while poor students necessarily don’t get less money than their affluent peers, they usually don’t get the extra money that funding advocates say is necessary for addressing additional needs. Here are some of the major takeaways.

1. A state’s high-poverty school districts usually don’t get more state and local money than its affluent districts.

In 20 states, both kinds of districts get about the same amount of money. In 12 states, more money went to impoverished districts. But in 16 states, more money actually went to wealthier districts, according to the Education Law Center report. (Alaska and Hawaii were excluded. And like the other reports in this piece, it uses data that are a few years old, in this case running through 2015.)

There were some notable outliers: New Jersey gives 20 percent more money to poor districts, for example, while Nevada gives poor districts 40 percent less.

Funding advocates say a flat distribution is nothing to celebrate, since there is evidence that poor students need more money spent on their schools to reach comparable outcomes.

2. High-poverty and low-poverty schools also tend to get about equal amounts of money from their districts.

Recent research has found that schools serving poorer students tend to get the same amount as, or even a tiny bit more than, other schools. But there are exceptions: in some of the least equitable districts, poor students and students of color get between $300 and $500 less than wealthier and white students.

Starting next school year, the federal education law requires states to report how much is spent at each individual school, which advocates are hoping to pressure districts with disparities to close them.

3. When you zoom out, things look worse for students in high-poverty schools, since they’re more likely to be located in states that spend less on education.

Spending disparities grow when you compare poor school districts nationwide to wealthier ones. Here’s why: poor students are more likely to live in states with weaker economies and that spend less on education.

For example, there’s a greater share of poor kids in Mississippi (which spends about $7,000 per student, according to the Education Law Center) than in Massachusetts (which spends about $15,000 per student).

Education Trust tried to quantify that disparity between states. The civil rights and education organization, led by former U.S. Education Secretary John King, found that American students in poor school districts get an average of about $1,000 less in state and local dollars than those in wealthier districts. This is also an important reminder that states spend widely varying amounts per student.

Bruce Baker, a Rutgers professor and the author of the Education Law Center report, said that gaps like these are concerning, though people should keep in mind that costs of living and other factors also vary. “When you start trying to compare nationally, you really have to find a way to thoroughly correct for a whole bunch of different cost factors,” he said.

4. But federal dollars generally do what they’re designed to do: make school spending more progressive.

The Urban Institute analysis shows that federal money — which accounts for only about 10 percent of total education spending — ensures that in almost all cases, poor districts end up with as much or more money than wealthier districts in the same state. (This doesn’t mean, though, that the federal dollars even out the disparities between states.)

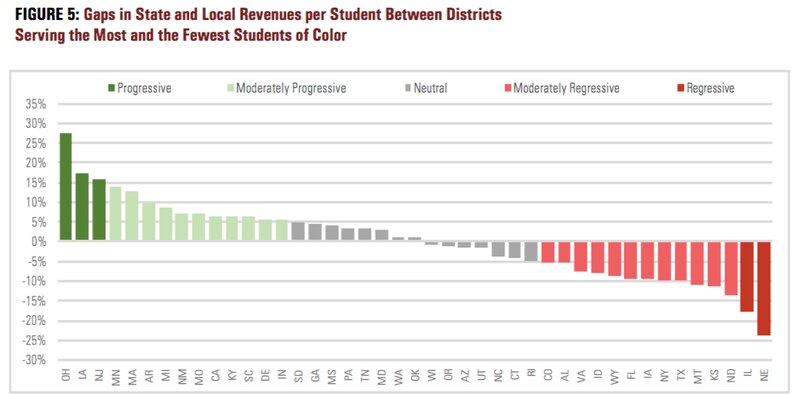

5. When you sort schools based on race, school spending disparities are even worse than when you sort schools by income.

Most studies of school funding gaps focus on those between higher- and lower-poverty schools. But the Education Trust report also compared how states fund districts with more students of color versus those with more white students.

In many cases there were substantial differences: 11 states that sent more or the same to poor districts actually sent less to districts with more students of color (and only one was the reverse).

Another recent analysis found that, even controlling for poverty, Pennsylvania school districts with more black students got less funding. An older study found that districts in the Chicago area with more Hispanic students were especially likely to be financially disadvantaged.

“It’s such a compelling data point for why poverty is not a good proxy for race,” said Ary Amerikaner of Education Trust.

6. There’s no correlation between how much a state spends on schools and whether more dollars go to poorer schools. There’s no correlation between a state’s political leaning and how progressively education dollars are distributed, either.

States that spend the most aren’t necessarily the ones that give the biggest share of money to high-poverty schools, as the New York-to-Utah comparison underscores. There’s also no clear political pattern, at least based on how a state voted for president in 2016, though there is research showing that Democratic governors generally mean more money for higher-poverty districts.