A warm classroom is not conducive to learning, as any student trying to pay attention to a teacher’s lecture on a hot day can attest. That’s not lost on teachers.

“I really dread school based on the weather, especially in the spring and in the fall,” said one teacher in Baltimore in a school without air conditioning. “If it’s really hot … certainly [student] engagement goes down.”

Now, there’s research to back that up.

A new study, released through National Bureau of Economic Research on Monday, shows that after a particularly hot year of school, high schoolers performed worse on the PSAT, an exam taken to prepare for the SAT and determine winners of the National Merit Scholarship.

“Hotter school days in the year prior to the test reduce learning, with extreme heat being particularly damaging and larger effects for low income and minority students,” write the paper’s four researchers. “On average, a 1 degree Fahrenheit hotter school year prior to the exam lowers scores by … slightly less than 1 percent of a year’s worth of learning.”

The research highlights how external factors can impact students’ performance on high-stakes tests, while also suggesting that air conditioning, still missing in many schools, is a worthwhile investment.

The study, which has not been formally peer-reviewed, relies on extensive data: PSAT data of 10 million students from the high school classes of 2001 to 2014.

Paper authors Joshua Goodman of Harvard, Michael Hurwitz of the College Board, Jisung Park of UCLA, and Jonathan Smith of Georgia State focus on whether students learn less, as measured by the PSAT, in school years with more hot days. (The College Board administers the PSAT.) To get at that, they look at students who took the test multiple times, and then, accounting for the fact that students generally perform better after taking the test again, they see if students tended to do worse when the exam was preceded by a warmer year.

Indeed that’s exactly what they find, with every degree increase in average temperature above 60 degrees during the school year, leading to slightly lower PSAT scores. More days with extreme heat — over 90 or 100 degrees — also caused score drops. Impacts were significantly larger for black and Hispanic students and those in lower-income areas.

Why might that be?

“Wealthier students may be able to compensate for lost learning time by getting additional instruction from their parents or private tutors,” the authors say. “Such students may also be more likely to attend schools where teachers have better capacity to compensate for lost learning time by adjusting lesson plans or adding more instructional time.”

Heat during the summer, weekends, and holidays didn’t impact test scores, which is consistent with the idea that learning in school drove the findings.

The study then turns to the question of whether air conditioning prevented the negative effects of heat on learning. They find, that in fact, it generally did, with most of harmful consequences of heat disappearing in schools that appear to have air conditioning.

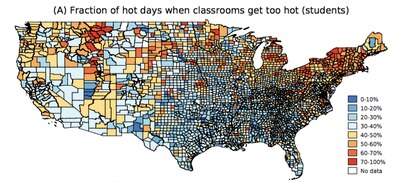

The paper doesn’t have perfect data on whether schools actually have and use air conditioning, but instead relies on surveys of counselors and students. A substantial number of students — about 42 percent — said that on hot days classrooms sometimes or frequently got too hot, though counselors were less likely to say this was an issue. Paradoxically, in hotter areas of the country, hot classrooms were less of a problem, likely because air conditioning was move prevalent.

Black and Hispanic students and those in low-income areas were a few percentage points less likely to have air-conditioned classroom than white or affluent students in similar climates. This may explain why those students saw steeper test score declines as the result of warm weather.

Because of this and the fact that black and Hispanic students tend to live in places with higher temperatures, the paper estimates that the impact of heat in schools explained somewhere from 1 percent to 13 percent of the racial test score gap on the PSAT.

The analysis is in line with other research on the topic, including a study of New York City showing that high school students do worse on end-of-year exams in years with higher temperature and on warmer testing days. (The latest paper doesn’t focus on the single testing-day effect because the PSAT was taken in October, when heat is less likely to be a concern.)

A recent analysis found that most of the country’s 50 largest school districts report having air conditioning in every classroom, but also that 11 districts have some or many classrooms without it.

Concerns about heat in school may have prompted some policymakers to promise action: New York City schools have vowed to install air conditioning in all classrooms by 2022.

It may well be a worthy investment, according to the latest study. “The benefits of school air conditioning likely outweigh the costs in most of the U.S., particularly given future predicted climate change,” the authors write.