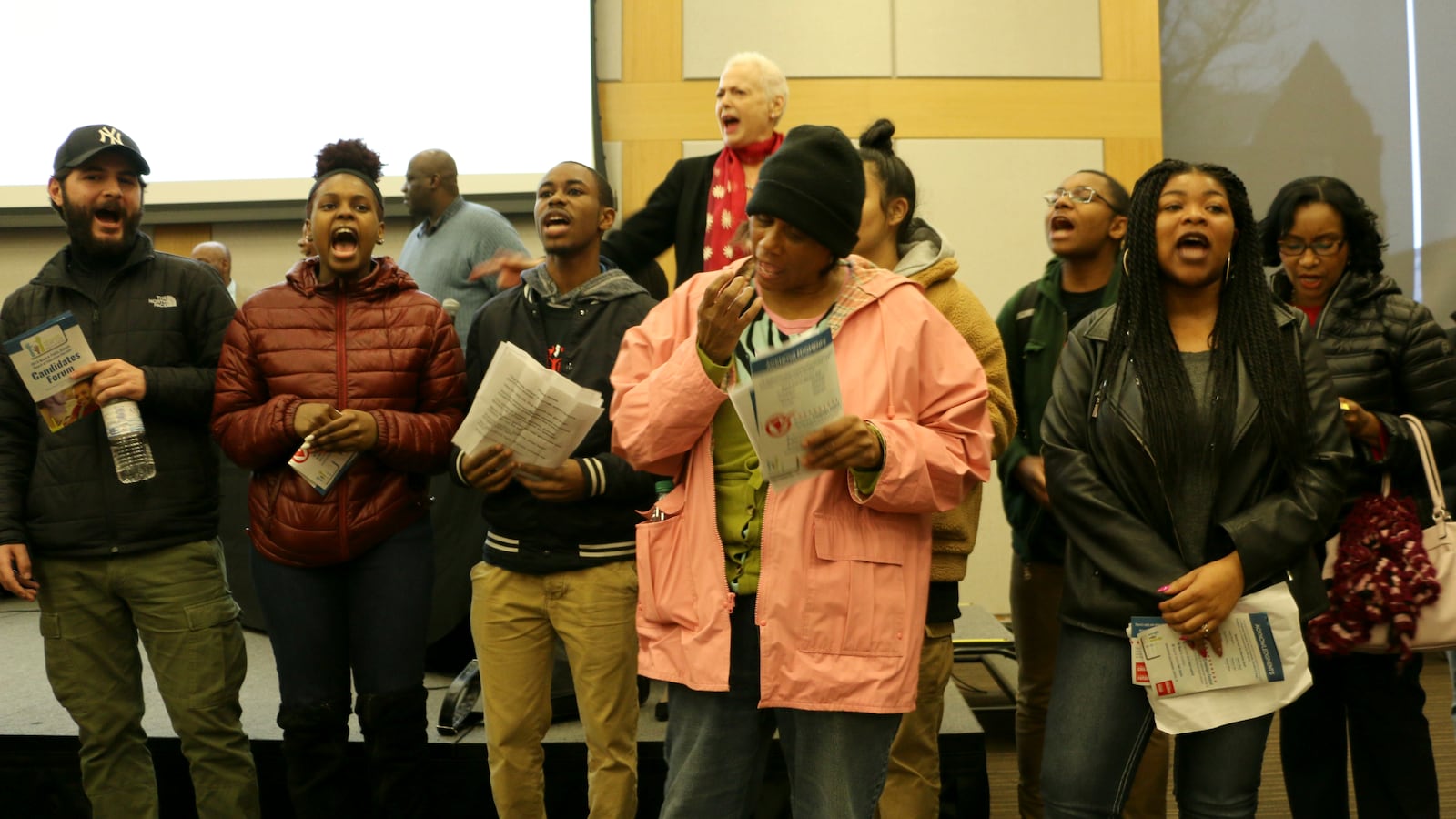

Debates about states taking over school districts are often deeply fraught.

“The right to vote to select your own representation is a right of what we call freedom,” said Dwight Gardner, a pastor in Gary, Indiana, where the state recently removed all sway from elected school board and gave even more power to the state-appointed emergency manager.

Race and racism is usually not far from these disputes. “Legislation adopted for ‘these people’ in ‘that place’ is how Jim Crow became law of the land,” Gardner said last month, pointing out that in some respects Gary, a predominantly black city, was being treated differently than Muncie, a majority-white district also being taken over.

In a new book, “Takeover,” Rutgers political scientist Domingo Morel concludes that the prevailing logic for takeovers is indeed tainted with racism. That’s based on an examination of data from every school district taken over by a state over a 30-plus year period, and case studies of the takeovers of Newark, New Jersey and Central Falls, Rhode Island.

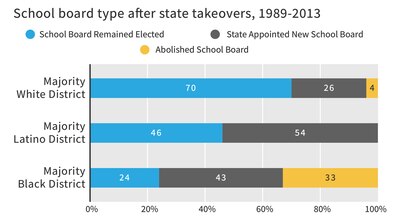

Predominantly black school districts are more likely to be taken over, Morel documents, and those takeovers are more likely to fully remove the elected school board. He also finds that cities with a greater share of black city council members are more likely to face takeovers, with state leaders arguing they must wrest control of chaotic local politics.

“Unlike previous groups, which had the opportunity to govern their cities for decades and fully participate in patronage practices, black communities and their political leaders were castigated for engaging in political practices as old as American politics,” Morel writes. Still, Morel concludes that school takeovers have been empowering for some communities of color.

They are provocative claims, and timely ones. A number of school districts taken over years or decades ago, including Detroit, New Orleans, Newark, and Philadelphia, have recently returned to local control. And debates are still live across the country — in Indiana, Kentucky, and Mississippi — about when states should intervene in districts where students appear not to be learning necessary academic skills.

Morel’s analysis has some key limits. He can’t prove why some districts are taken over or others are not, and “Takeover” focuses on political, not academic, ramifications of the moves — though some research has found takeovers do improve academic outcomes. He also doesn’t spend much time in the book backing up his claims that collaboration between schools and communities is a better strategy for improving academics.

Chalkbeat asked Morel more about his book and his conclusions. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Chalkbeat: One thing that surprised me that I learned from your book was the relative recency of state takeovers of school districts as a strategy. Can you tell me when and where the idea started and how it spread?

Domingo Morel: I go back and I trace the idea to New Jersey, which happens to be the first state to take over a school district, and that idea going back to at least the 1960s. But states actually passing laws to take over school districts — that doesn’t start happening until the 1980s. New Jersey being the first state in 1989; they take over the Jersey City school district. But then it spreads out beyond New Jersey.

My research is based on data looking at the 1980s up to 2013. Up to that point, we’ve had about 100 takeovers. Since then there’s been a couple more — probably 105, 107 or so.

How many states have takeover laws currently?

So as of 2017, 33 states had takeover laws and by then 22 states had actually taken over school districts.

What is your overarching thesis about state takeovers?

I think people don’t pay enough attention to how political education is — that education in the country is a political project. I think that’s the most important thing that I think we need to understand. And so if education is a political project, when we think about reforms, we need to think about them as political objectives as well. And so if we’re going to take over a school district, it just doesn’t seem consistent with what the literature says about improving schools that you just remove a community from the entire decision-making process. Because what the literature tells us in education is — and it’s just very intuitive — if you look at school districts across the country who are doing well, everybody has a stake in the school district.

But then we get still the expansion of takeovers. It suggests that there’s something else there. And this is where I come in and say that we need to understand historically role that education has played in communities and what type of power it gives a community.

If we look at education as a political problem and we see how important the schools are to communities’ political empowerment, then we can start to see how how takeovers make sense for two major reasons: Conservatives had consolidated within the Republican Party by the 1970s and blacks became an important part of the Democratic coalition by the 1970s. Moreover, the schools served as the political foundation for black political empowerment. This provided the context for increasing political tension between increasingly conservative state governments and cities. The schools were a major part of this political struggle.

Second, cities began to win court cases to secure more school funding from state governments, which led to further tensions.

Reed Hastings, the Netflix founder, charter school advocate, and education reform funder, has said that “the school board model works reasonably well in suburban districts” but that the politically ambitious “use the school board as a stepping stone to run for higher office” in cities. And I take your argument to be, yes it’s true that the school board can be a stepping stone, but that has proven crucial for the political empowerment of communities of color. Can you speak to that?

Let’s think about that comment and put it in perspective. So what he’s saying is democracy works for certain communities but it can’t work for others. Yes, you have ambitious people, but you also have people who are just interested being school board members. But even if you have ambitious people who want to be city council people, mayors, and so forth, why is that a justification for saying that school boards are not important?

And so the message that sends is that democracy is worth fighting for and worth having in certain places and not in others because it may seem like it’s more messy in big cities and urban areas. And I say it “may seem” like that because I don’t think there’s any evidence that you find more corruption or people are not as prepared to be school board members in urban localities compared to suburban or rural — there’s just no research to support that.

You make a connection in your book between school funding and takeovers, arguing when school districts push for more resources, they face a greater chance of being taken over. Can you explain that?

What I find in the research and this period, in what I call the incubation period from 1982 to 2000, there were 18 states where plaintiffs actually won school funding court cases. And in 14 out of those 18 states, we see takeover laws pass after they win these court cases and the only states where they didn’t were some of the whitest states in the country: Montana, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming. In this incubation period, if plaintiffs did not win court cases securing more resources for the school, we actually don’t get takeover laws passed during this time.

Has that trend continued?

Between 2000 and 2015, you had about 17 other states that passed takeover laws, and I haven’t studied all of them as related to state funding litigation. What I do know is that most takeovers that have happened across the country happened in those first 14 states.

One response might be, there may be different motives, but it really is true that places that have seen state takeovers, also had low academic achievement. And why not just take that at face value as the reason why?

I think that’s a fair point, as these school districts have struggled. My response will be multi-level here. The first is that we have a lot of students who have struggled and are currently struggling but they don’t experience takeovers. Takeovers are relegated to a particular community.

The second part is that if we’re interested in improving schools, I go back to what we know works with improving schools, which is a collaboration. That doesn’t mean that a state doesn’t intervene, that a state is not involved.

What I’m suggesting here is that if we look historically at the reasons why schools struggle, the premise behind the takeover is that the community is the problem, whereas I say if we look at it historically, we see that the community is not the basis for the problem, that in fact communities have been doing what they should be doing to improve schools. There are models of collaboration that are out there to improve school districts that do not involve coming in and taking it away from the community.

Let’s talk about the research on academic gains from state takeovers. I know that’s not the focus of your book, but advocates for state takeovers could point to studies of New Orleans and in Newark, after three years, to say look, it has been successful in boosting test scores in some contexts.

My response to this is multi-level. The first is that it’s contested to what degree these academic scores actually improved. But I spend very little time on this because as a political scientist, I’m interested in the politics of this mostly. What I will say is, OK, so let’s just agree that test scores have improved. What has been the cost of test scores’ improvement in New Orleans for example?

In New Orleans, 25 percent of the black teachers lose their jobs. Seven thousand people lose their jobs. The school board was removed from the political process. The school governance was based on a two-tier level: one is the state-created board made up of people that are not from New Orleans and the second is actual charter school governing bodies, 60 percent of which have white members although 67 percent of the community is African-American. And so all of that is the price that the city of New Orleans — that black New Orleans — has to pay for contested improved test scores.

You do talk about some contexts where, in your view, the state takeovers have been successful and that is often with Latino communities. Can you talk about one or two cases where you’ve seen it as successful and why it’s been successful?

The city of Central Falls is a community that was essentially marginalized before the takeover. The takeover comes in and the state is invested in helping that community become part of the decision-making process. And over time, you have a state government working together with city officials and school boards to improve outcomes.

And so what I find is that this is most likely to happen in states where you have Democratic state administrations that essentially rely on that particular city for its political power. You have what I call cohesive regimes, where state government doesn’t take for granted that local government because it needs that local government in order to to be in power and vice versa. That’s why Central Falls is a case where a takeover has not been detrimental to that community.

Scholars in Harvard have looked at the city of Lawrence, Massachusetts and have shown how that has led to improved academic measurements there. Lawrence is another place where I would argue, for the most part, state government has not treated the city of Lawrence and its leadership there the way that you see Chris Christie treat Newark or Louisiana treat New Orleans and so forth.

And you show that in Central Falls and in Newark that Latino representation on the school board actually increased after the state takeover, correct?

Absolutely. The data that I have over time from the 1980s to 2013 show it’s consistent with this — that Latino communities actually benefit in their representation on school boards actually increase after takeovers.

And the opposite is true for black communities.

Yeah, we see that over time takeovers lead to decreased representation for black communities.

One thing that I think is interesting is that once school choice and charter models are put in place through state takeovers, it becomes difficult to fully remove them or go back. The departing superintendent in Camden said in an interview after he announced that he was leaving — talking about “renaissance schools,” which are these charter–district hybrids — he said, “Those are schools that have already over a thousand students and families who have supported and advocated for it. You can’t unwind that.” I thought that was really interesting in the sense that even after a district maybe returned to local control, the system is set up to be politically sustainable.

Absolutely. I think that’s the reason why we’re seeing the recurrence of local control in districts and we’re going to continue to see more of them.

Obviously, it’s the case in New Orleans, where 95 percent of the schools are charter schools. It’s the case in the case of Philadelphia; to some degree it’s the case in Newark. I think that these folks are like, this is in place and it is not going to go anywhere, essentially because the train has left the station.

I go back to Newark: 30 percent of the schools are now charter schools. From the perspective of charter critics in the community, now the political struggle is to prevent that 30 percent from going to 50, 60, or 70 percent.

One thing that might be surprising to some people is that at the end of your book, you advocate for an increased federal role in schools. That seems at tension with the skepticism of state takeovers. Can you talk about that?

It’s a good point. The major issue for the communities is twofold. One is lack of resources and two, when you ask for these resources, it makes you susceptible for intervention that leads to your removal. In thinking about the potential solutions to these two problems, there’s ample opportunity and space there for the federal government to provide funding, since right now they only provide about 10 percent of funding to these localities. And then on the political side, for the federal government to provide the protections to keep local communities able to decide what happens here.

The proposal here is not saying that the federal government comes and intervenes in the way that states have intervened — all I’m saying is more funding and political protection.