The Trump administration’s decision to withdraw guidance dealing with race in school admissions last week wasn’t just about colleges.

School districts across the country have grappled with how to integrate their schools, too. And one of the seven documents withdrawn by the education and justice departments offered a roadmap for districts looking to voluntarily integrate their elementary and secondary schools.

This move is important symbolically — particularly in light of a surge of discussions about the persistence of segregation in public schools. But it’s not likely to have far-reaching policy implications, since only a handful of districts voluntarily use race in school assignment decisions.

Here’s what we know about what this change might mean for K-12 schools. Keep in mind that the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, who has authored a number of the key affirmative action opinions, puts things in even more flux. Critics of affirmative action hope Kennedy’s replacement will join other conservative judges to further limit the consideration of race in state and local policies, including school admissions decisions.

What was this guidance?

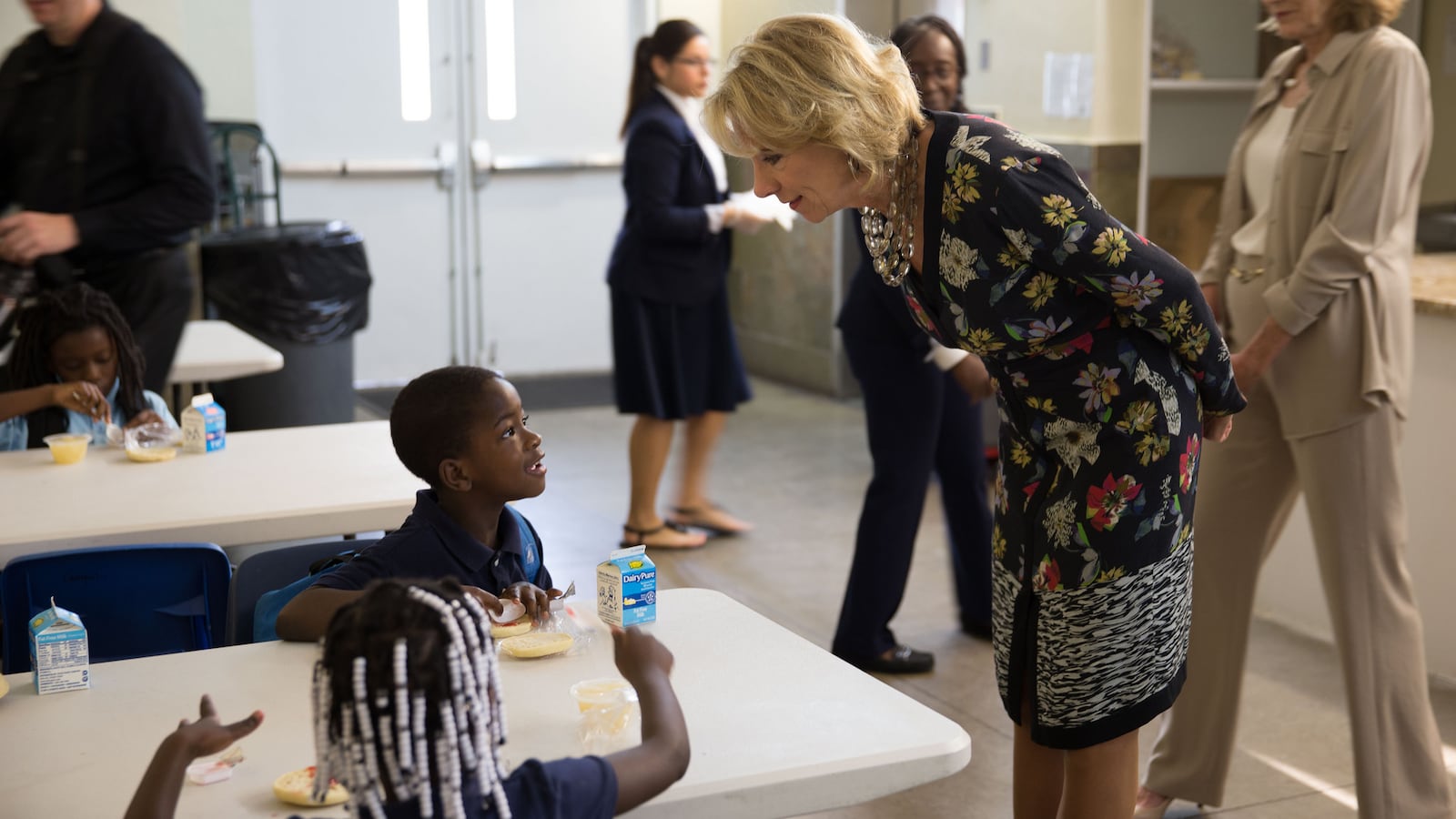

What’s relevant to K-12 education is a 14-page Obama-era document that explained how school districts can attempt to racially integrate schools without getting into legal trouble. (The document was targeted at districts that wanted to adopt desegregation policies on their own, not districts bound by federal desegregation orders.) That’s what DeVos rescinded.

It offered advice for school districts looking to make policy changes to diversify schools. Districts should first consider factors like students’ neighborhood or poverty level. But, the guidance read, “if a school district determines that these types of approaches would be unworkable, it may consider using an individual student’s race as one factor among others.”

It’s hardly a push for wide-scale race-based policies, but it left some room to use race if districts find they had exhausted alternatives.

This guidance was necessary, some argue, because the Supreme Court has weighed in on this issue in a complex way. A 2007 case, Parents Involved v. Seattle School District, struck down Seattle’s school assignment plan for its reliance on race to make admissions decisions.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in a widely quoted passage of the opinion. But Kennedy, the key fifth justice in the majority, didn’t fully sign on to this — continuing to allow districts to use race as a factor, but not the sole one.

“A district may consider it a compelling interest to achieve a diverse student population. Race may be one component of that diversity, but other demographic factors, plus special talents and needs, should also be considered,” Kennedy wrote. “What the government is not permitted to do … is to classify every student on the basis of race and to assign each of them to schools based on that classification.”

The Bush administration issued its own interpretation of the ruling in 2008, encouraging school districts not to consider race, though it did not say that doing so was prohibited in all circumstances. By publishing a guide for using race in 2011, the Obama administration was offering practical help but also sending a message that its goals were different.

Erica Frankenberg, a professor who studies K-12 desegregation at Penn State, said the user-friendly way the guide was written was part of the Obama administration’s strategy to encourage districts to integrate their schools.

Did any school districts use it?

According to recent research, 60 school districts in 25 states have school assignment policies meant to create more diverse schools. Of those, just 12 districts take race into account, rather than just socio-economic status. (Using socio-economic status isn’t affected by this debate about race-based admissions.)

But it’s hard to tell if the guidance was a deciding factor for any school districts.

“Even with the 2011 guidance in place, voluntary integration is still an incredibly complicated thing to do,” said Frankenberg. In addition to a plan being in compliance with the law, this approach require garnering political will and tackling logistics like transportation.

Why are some people concerned about it being rescinded?

The guidance represents the official viewpoint of the administration, but the underlying law hasn’t changed. It does mean that districts won’t have the backing of federal government when it comes to race-conscious integration policies. That might make districts using race more fearful of a lawsuit.

“This is a legal intimidation strategy from a very conservative administration that is really intent on not having race a part of decision making and policy,” said Liliana Garces, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin who studies race, law, and education.

The move to rescind the documents fall into set of decisions by the Department of Education to deprioritize voluntary desegregation. Last year, the department discontinued an Obama-era grant program that was intended to help schools increase socio-economic diversity. (According to The Atlantic, 26 districts had been interested in applying for integration grants before that program was scrapped by the DeVos administration.)

“To no longer have [the guidances] as an official stance is certainly at the very least, a missed opportunity to use the bully pulpit,” said Frankenberg, who supports race-based integration efforts.

Others support the move, arguing that attempts to use race in public policy are unconstitutional.

“Being opposed to racial preferences is not being against diversity, which is what the critics will claim: It’s simply being against discrimination,” Roger Clegg, of the anti-affirmative action Center for Equal Opportunity, told Education Week. “The federal government should not be going out of its way to encourage such discrimination.”

What does research say about school integration?

It’s found that low-income students and students of color benefit from racially integrated schools. One recent study found that graduation rates of black and Hispanic students fell modestly after the end of a court order mandating desegregation plans. Another study found that Palo Alto’s school integration program led to big boosts in college enrollment among students of color (though, surprisingly, also led to an uptick in arrests).

Research has also shown that income is not a good proxy for race when looking at academic outcomes — even when accounting for differences in family income, black students were substantially less likely to complete high school and enroll in college. Other research has shown that attempting to use income to integrate schools by race isn’t nearly as effective as using race directly.