The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is giving away $92 million to help schools work together and use data to solve problems, it announced Tuesday, part of a $460 million plan to help more poor students and students of color graduate high school and college.

Most of the 19 new grants are going to nonprofit organizations, including a group of urban California districts and New Visions, a New York City-based network. One grant is going to a district, Baltimore City Public Schools.

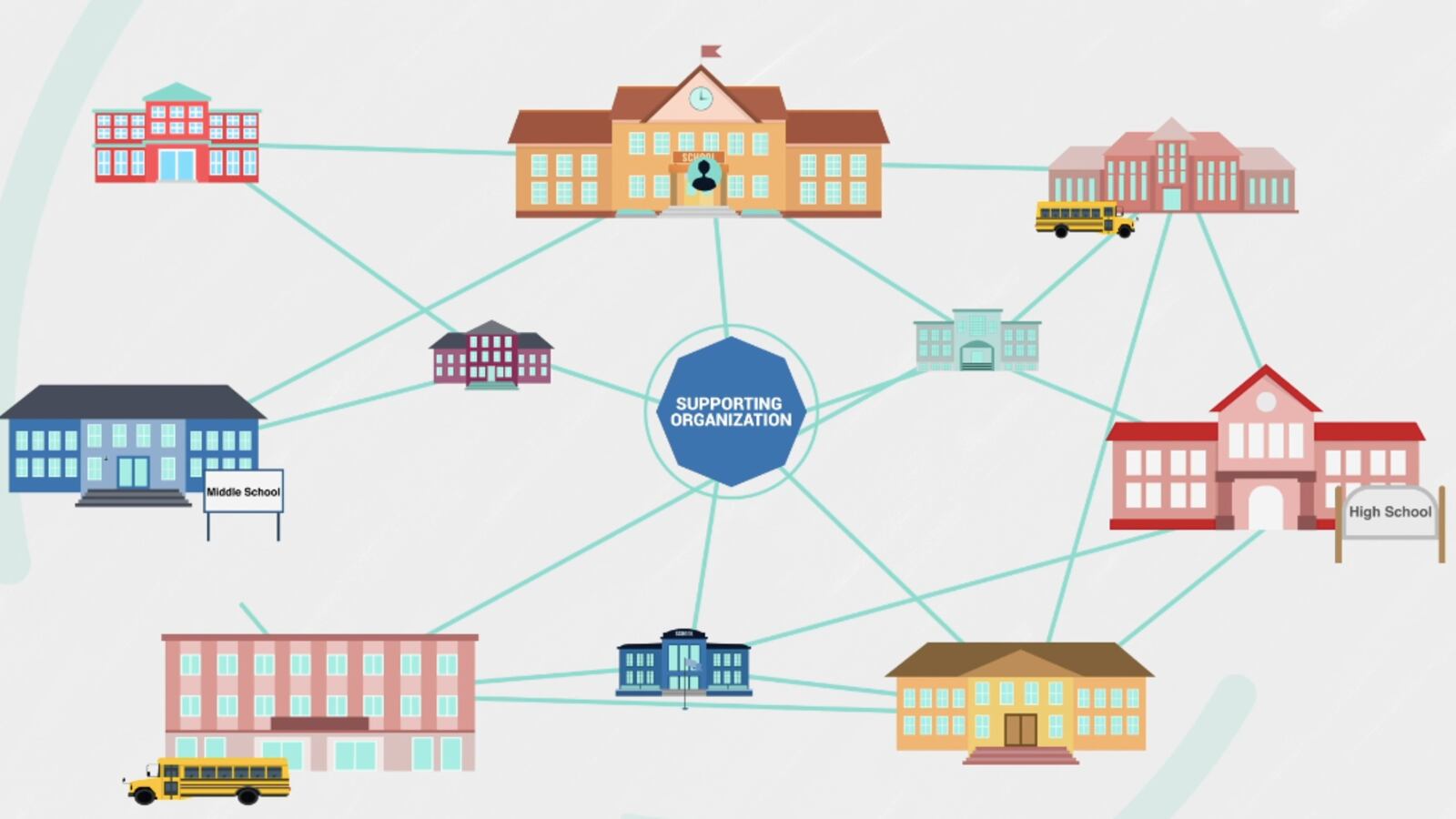

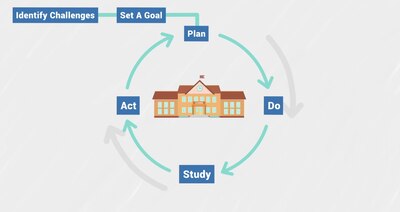

All have plans to convene middle and high schools in a “continuous improvement” cycle that uses data to improve student outcomes, though their approaches vary.

“Rather than coming in with a bright shiny new idea, we’re asking districts, schools, and intermediaries to look at investments they’ve already made,” Bob Hughes, the director of the Foundation’s K-12 education work, told reporters on Monday. “We’re really trying to build on what’s there, and really empower educators to continue the work that they’ve done but get the extra resources they need to finish the job.”

It’s a lot of money, likely to make an impact on the affected schools. But it still amounts to a scaling back of the ambitions of the Gates Foundation, which spent the last decade pushing for sweeping changes to teacher evaluation rules and academic standards across the country. (Gates is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

The change in direction, announced last year, reflects lessons learned learned by the influential foundation, it said. Critics have argued that Gates has been heavy-handed in pushing its ideas about how education needed to change, even as those efforts yielded disappointing results, as its teacher evaluation work did in one recent study.

The focus on expanding local initiatives might make educators more amenable to the foundation’s approach, though it is also likely to limit how widely felt the initiatives are. And whether the network approach of “continuous improvement” is likely to help schools get more kids ready for college, and what the Gates grants will mean for how schools are run, isn’t clear.

The grants include half a million dollars over two years to Achieve Atlanta, which plans to “develop a tool to support the successful matching of [Atlanta] students to good-fit colleges.”

The KIPP Foundation got half a million dollars to “convene and support its network of college counselors at its 31 KIPP high schools across 16 states,” among other strategies for helping students prepare for college, over two years.

New Visions for Public Schools, which the Gates Foundation’s Hughes used to lead, got a nearly $14 million grant to use data to help students succeed with advanced coursework in up to 67 high schools over five years.

The Network for College Success plans to support 15-20 Chicago high schools by “testing which student, teacher, and school interventions create the school conditions that build upon the abilities, intelligence, and creativity of Chicago’s youth.” The group got $11.7 million over five years to do so.

And in Memphis, a partnership called Seeding Success will get $560,000 to work with the school district to track students at 15 middle and high schools and help them stay on the path to high school graduation.

Gates’ emphasis on nonprofit intermediaries would seem to overlook the existing “networks” of schools: school districts. Hughes said that although just one grant had gone to a district, others went to organizations already working closely with districts, and he expects more districts to receive funding in the future.

The Dallas school superintendent, Michael Hinojosa, said he was excited about the $7.4 million grant going to the Institute for Learning, a training and consulting group affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh, to work with a group of schools there to improve students’ writing skills.

Meanwhile, the research behind the approach is thin. An analysis funded by the Gates Foundation, released by a Columbia Law School research center last week, identified a number of qualities of more or less successful networks. But it was only able to find two studies examining whether this network approach led to better student outcomes.

“I don’t think the research base is fully developed, and that’s one reason we’re making these investments,” said Hughes. The report “underscores the fact that there are lots of places with complex social problems that have used continuous improvement to improve performance in their respective organizations,” he added.

The paper cites a hospital, a nonprofit healthcare organization, and a network of juvenile justice agencies among those using the strategy with success. Evidence in several of those cases does not seem to rely on external research, but internal reports or claims from the organizations’ websites.

The foundation, which has also turned its gaze to improving curriculum in schools, expects to announce new grants this fall.

Read the full list of new Gates grants here.