Sending would-be educators into schools for a year of intense, hands-on training alongside their academic coursework is a concept that’s excited a lot of people who want to improve how teachers learn to teach.

But enthusiasm for these teacher residency programs has largely outstripped their ability to expand, especially because many charge little or no tuition.

Now, the state with the most students in the country is trying to change that. California recently earmarked $75 million to create new residencies and expand existing ones — enough to jumpstart programs that face unique funding challenges. Advocates hope these programs will give teachers better training, improve their likelihood of staying in the classroom, and diversify the profession.

“The $75 million by far is the largest state investment that I can track by leaps and bounds,” said Tamara Azar of the National Center for Teacher Residencies.

California’s school districts or charter schools will be able to win the money by partnering with an existing teacher-prep program on a residency designed for prospective math, science, special education, and bilingual teachers — who are all in high demand in a state with teacher shortages.

Winning districts can’t charge prospective teachers an up-front fee, though the university partners may charge tuition. Some programs might offer living stipends to candidates, a practice promoted by the Learning Policy Institute, a California-based think tank that supports the residency model.

Teachers who go through the programs have to commit to teaching for four years in the district or school that sponsors the residency, and if they leave early they’re on the hook to pay back some of the grant funding.

Even with that kind of commitment, earning a stipend instead of paying tuition makes residencies more appealing to some would-be teachers than traditional teacher education. (Nationally, not all residencies offer stipends and some still charge tuition.) But that dynamic has left programs with big costs, and most remain relatively small.

The Learning Policy Institute counted 53 residency programs in 2016. The National Center for Teacher Residencies estimates that the 23 programs in its network have produced fewer than 3,500 graduates, including 792 last school year. For perspective, there were nearly 200,000 first-year public school teachers across the U.S. in the 2015-16 school year.

“Residencies have grown relatively slowly,” said Azar.

California expects its initiative to produce around 3,700 teachers.

Existing residency programs fund themselves in a patchwork of ways: philanthropic contributions, school districts, federal grants, state programs, and the teacher candidates themselves. Bank Street College of Education has offered other ideas for more sustainable financing, including using residents as substitute teachers or to run after-school programs.

To date, research on the residency model is limited, and there’s not clear evidence that residencies are any more effective at training teachers. In fact, a study of one highly touted program, the Boston Teacher Residency, found its graduates were less effective at raising student test scores in math than other novice teachers, though by year four in the classroom they were more effective.

There is evidence that teachers trained as residents are more likely to remain in the classroom for a number of years. Residencies are also able to recruit many more teachers of color, which is notable amid pushes to diversify the predominantly white profession.

“I think that amount of student teaching and the mentor teacher being a true expert probably has a lot to do with the retention rate being strong,” Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the Learning Policy Institute, has said. “You’re getting everything a beginning teacher should get.”

Twelve California districts have already won small grants to start planning for new or expanding residency programs.

Under the terms of California’s grant program, every dollar a program receives from the state has to be matched with another dollar from other sources. Prospective teachers will take courses in classroom management, child development, and culturally responsive teaching, among other areas, through an existing teacher prep program, likely a university. They will also student-teach at least half-time for a full school year with support from a teacher with at least three years of experience.

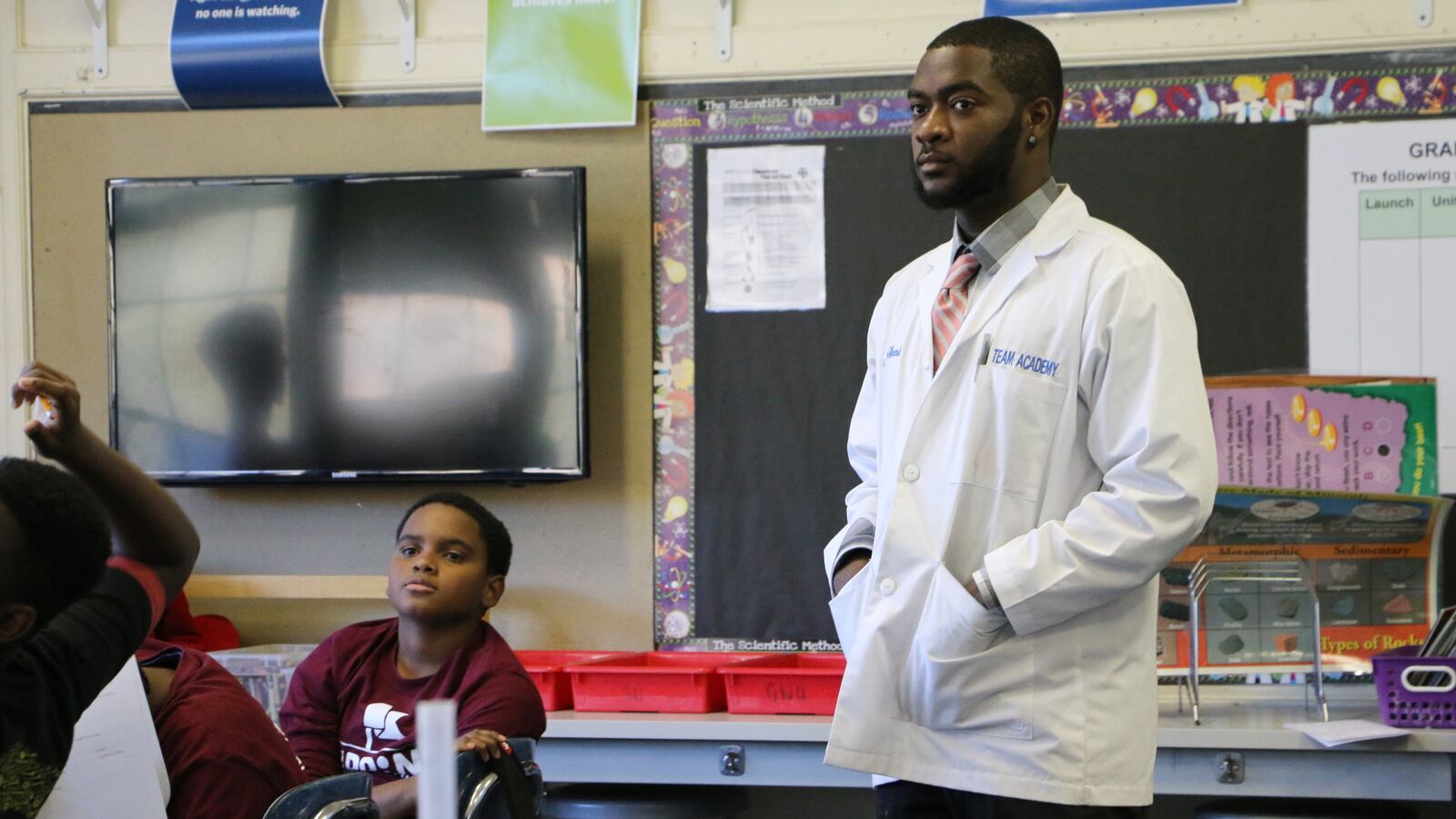

In Newark, the KIPP charter network runs a year-long residency for would-be teachers who take classes through Relay Graduate School of Education. Intisar Hatcher-Wright, a KIPP science teacher who has been mentoring resident Yumar Wheeler, said the approach doesn’t entirely shield people from the challenges of the classroom — but hopefully eases the transition.

“It’s been a huge learning curve for Yumar. It hasn’t been easy for him by far,” Hatcher-Wright said. “But I will say that what has been maybe different … than he might have experienced otherwise is that I was really purposeful in protecting him and making sure he could take baby steps before he takes these larger steps.”