A recent report offered a surprisingly rosy picture of the state of teacher diversity. The number of teachers of color in public schools, it noted, had more than doubled over the last three decades.

“Our findings are different than the conventional wisdom,” Richard Ingersoll of the University of Pennsylvania, one of the authors of the research, told Chalkbeat. Teacher diversity still doesn’t mirror student diversity, he acknowledged. But “there is sort of an unheralded victory,” he said.

You may be getting whiplash. Isn’t the teaching profession overwhelmingly white? Hasn’t progress been modest, at best?

Here’s what you should know about the demographics of America’s teaching force, and how to make sense of these competing narratives.

Teachers of color are still a small share of the teaching force.

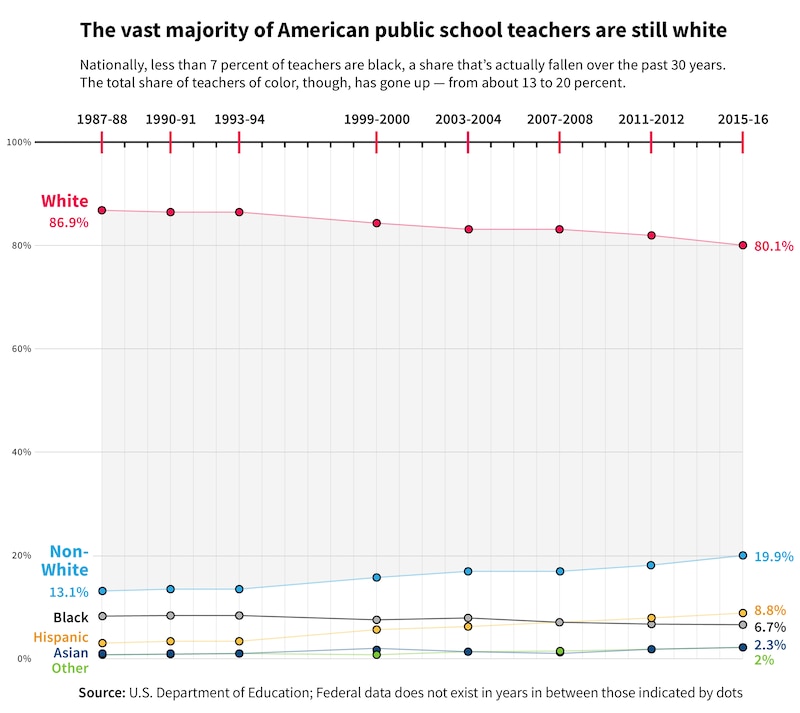

Here are the basic numbers, based on federal data: In 1987, about 87 percent of public school teachers were white. In the 2015-16 school year, just over 80 percent of teachers were white.

During that same time period, the raw number of teachers of color went from 305,000 out of well over 2 million teachers to about 760,000 out of nearly 4 million teachers.

(In all cases, we’re referring only to public school teachers, and not counting those at private schools.)

That means there are a few ways to frame the exact same data: You could emphasize, as Ingersoll does, that the number of teachers of color has increased by 150 percent in nearly three decades. But you could also say that the share of teachers of color has increased only 7 percentage points during that time.

Both are accurate, though they suggest very different stories.

The 150 percent increase looks so large in part because there were few teachers of color to begin with. It’s also focusing on the raw numbers at a time when total number of teachers has ballooned.

That means the raw increase doesn’t translate to teachers of color making up much more of the profession. The teaching force remains overwhelmingly white, even as about half of the students attending public schools in the U.S. are students of color.

One other note: Ingersoll’s report actually states that the increase in teachers of color was 162 percent, not 150 percent. After Chalkbeat pointed out an inconsistency in the data, Ingersoll recalculated the numbers to reach 150 percent. He says the error was due to a discrepancy in an older federal report.

The statistics are particularly grim for black teachers.

Between 1987 and 2015, the number of black teachers increased from around 191,000 to 256,000. But the share of teachers who are black has actually declined, from 8.2 percent to 6.7 percent. That’s possible, again, because the teaching corps as a whole has grown significantly during that same period, outpacing the increase in students.

One reason that matters? A great deal of research showing how teachers of color benefit students of color has focused specifically on black teachers of black students.

These trends haven’t played out the same way for all teachers of color. Over that same period, the number and the share of Hispanic teachers have both grown substantially, jumping from 69,000 to 338,000 and from 3 to 8.8 percent of the total teaching force.

Why has the progress, in terms of increasing the share of non-white teachers, been so modest?

Ingersoll documents that teachers of color have particularly high turnover rates, and shows that largely a function of where they work: in segregated schools that have particularly high attrition rates. That’s in line with other detailed research out of North Carolina.

Additional expectations of teachers of color — such as black men being tasked with serving as disciplinarians — also may contribute to burnout.

Other possible explanations include certification processes that disproportionately screen out prospective teachers of color; the stagnation in teacher salaries over a similar period; and schools of education that may not prioritize recruiting students of color.