Trump administration officials say it’s time to reverse Obama-era guidelines meant to curb suspensions and expulsions, especially for students of color.

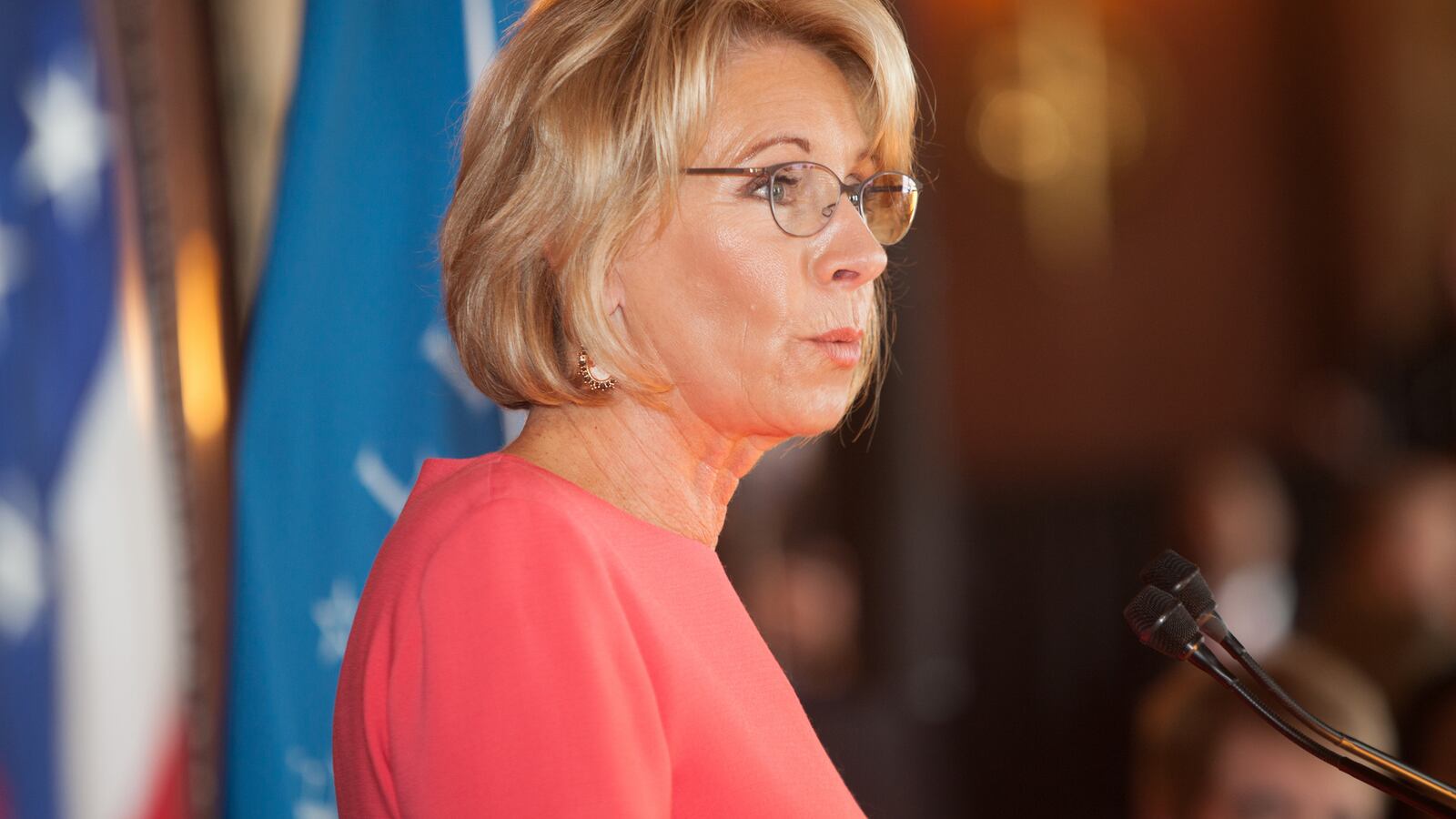

The federal school safety commission recommended the move in a report released Tuesday, saying that efforts to address racial disparities in discipline may have made America’s schools less safe. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is expected to rescind the guidance soon, notching a victory for the conservative campaign to link school discipline reforms with unsafe schools — a connection that remains questionable.

“One of the things that the commission was concerned with was the recurring narrative that teachers in the classroom or students in the hallway and on campus were afraid because individuals who had a history of anti-social or in some instances, aggressive, trending toward violent, behavior were left unpunished or were left unchecked,” a senior Trump administration official told reporters Tuesday. “So that is the first move that the report makes, to correct for that problem.”

The school safety commission’s 177-page report also recommends:

- More access to mental health services for students

- Various approaches to school safety, which could include considering “arming some specially selected and trained school personnel”

- More training around how to prepare for an active shooter

Those conclusions come from a commission formed after a school shooter in Parkland, Florida left 17 dead in February. Chaired by DeVos and composed of just four members of President Trump’s cabinet, the commission has hosted a series of hearings and courted controversy by avoiding discussion of gun control measures.

While the report lauded states and schools using techniques such as positive behavioral interventions and supports to tackle student misbehavior, the commission stopped short of calling for more federal funding for such initiatives.

Scrapping the school discipline guidance is a particularly notable move. That guidance was issued in January 2014 by the Obama education and justice departments, and it told school leaders to seek out alternatives to suspension and other penalties that take students out of the classroom.

It also noted that black and Hispanic students were suspended much more often than other students, and that suspensions were correlated with higher dropout rates and lower academic achievement. Significant, unexplained racial disparities in discipline rates could trigger a federal review into whether a district had violated civil rights law, it warned.

To civil rights leaders, this was an effort to address racism in schools. To conservatives, it represented government overreach. In schools where suspensions were reduced without alternatives, the guidance encouraged misbehavior to go unchecked, they argued.

That argument is expanded in the safety commission’s report.

“When school leaders focus on aggregate school discipline numbers rather than the specific circumstances and conduct that underlie each matter, schools become less safe,” the report says. It cites a survey from the AASA, The School Superintendents Association, with comments like, “There is a feeling that by keeping some students in school, we are risking the safety of students.”

(AASA’s advocacy director, who praised some aspects of the report, says those comments represented a minority view.)

There’s limited research evidence that cutting back on suspensions made schools less safe, though teachers in multiple districts have reported that they have been hamstrung by new restrictions. One study in Chicago found that when the district modestly cut down on suspensions, student test scores and attendance actually rose as a result. There’s also not much known about how effective alternatives, like restorative justice, have been either.

The report also argues that guidance rests on shaky legal ground by relying on the concept of “disparate impact” — meaning policies that are neutral on their face but have varying effects on different races can be considered discriminatory.

Meanwhile, the report says, disparities in discipline rates may not have to do with discrimination at all, but “may be due to societal factors other than race.” It also says “local circumstances” may play a role in behavior differences “if students come from distressed communities and face significant trauma.”

“When there is evidence beyond a mere statistical disparity that educational programs and policies may violate the federal prohibition on racial discrimination, this Administration will act swiftly and decisively to investigate and remedy any discrimination,” it says.

The Obama-era guidance didn’t require schools to adopt specific policies, and rescinding it won’t require districts to make changes, either. But a change could influence school districts’ decisionmaking.

That’s likely to harm students of color and students with disabilities, former Obama education secretaries Arne Duncan and John King said in a statement.

“Today’s recommendation to roll back guidance that would protect students from unfair, systemic school discipline practices is beyond disheartening,” they said.

Read the entire report here:

Matt Barnum contributed reporting.