Are charter schools “draining,” “siphoning,” or “funneling” resources away from school districts?

It’s an argument at the heart of the increasingly contentious national debate over charter schools.

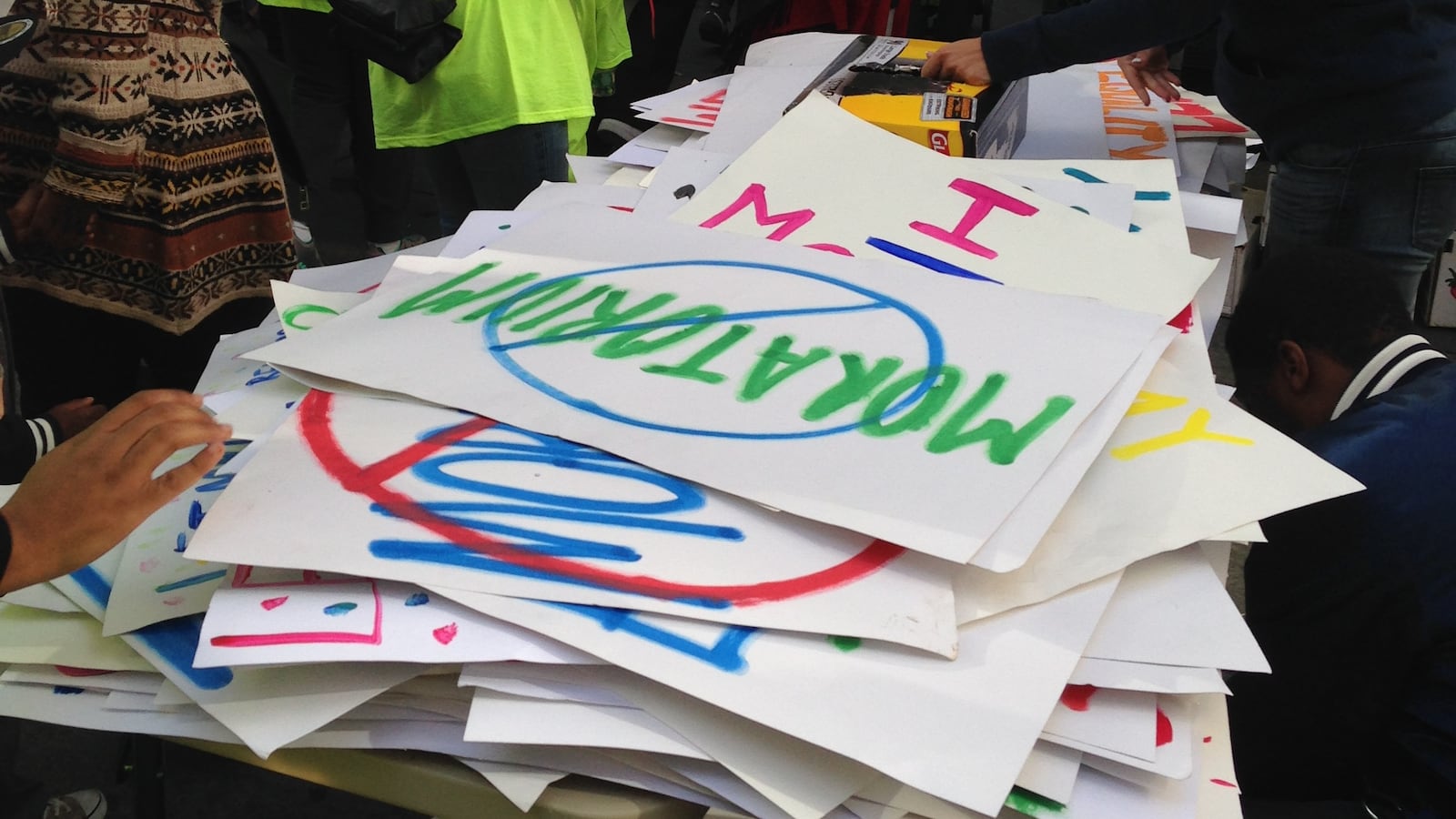

“I’m striking to stop charter schools from draining our schools,” wrote Los Angeles teacher Adriana Chavira during the January teachers strike, saying her school has had to cut teachers as it lost students to charter schools. A number of states, most prominently California, are considering efforts to limit charter school expansion in response to such concerns.

Presidential candidates like Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden have recently raised it, too. “The bottom line is, it siphons off money for our public schools, which are already in enough trouble,” Biden said of some charters.

Charter school supporters say that ignores the potential benefits to students — and that the funding argument misses the point.

“Do charters drain funding from our public schools? How could they? Charters are public schools,” wrote David Osborne, a charter supporter. “They do drain funding from traditional school districts, but that’s because parents have proactively pulled their children out of district schools and placed them in charter schools.”

The politics of the issue are so charged that it can be hard to separate fact from fiction. But charters have also been around long enough for there to be good answers to questions about what happens to traditional district schools when charter schools arrive.

Here’s the short of it: Charter schools really do divert money from school districts. Those districts can make up for that by cutting costs over time. But the process of doing so is often fraught, especially because the most straightforward way to reduce costs is to close schools.

Here’s why growth of charter schools often puts financial strain on school districts.

Imagine a school district with 10 schools each with 100 students. A new charter school opens in the district and attracts 100 students itself, 10 students from each existing school.

Each district school now has less money, since the schools receive money for each child enrolled, and each is serving just 90.

That leads to a budget crunch. Cutting some costs, like the number of teachers, may be relatively straightforward (though still often painful). Other costs, like the principal’s salary and building maintenance, stay the same whether the school is serving 90 or 100 students.

To close the gap, the schools might cut an art teacher, cancel an after school program, or increase class sizes.

“Typically, at least in the short and even the medium term, public schools can’t cut costs commensurate with the amount of revenue that they’re losing” as students exit for charters, said Bob Bifulco, a Syracuse University professor who has studied the impact of charter growth in New York districts.

In reality, charters aren’t the only cause of financial challenges faced by districts. Students leave for schools in other towns or private schools, and many districts also grapple with limited state funding or unwieldy pension obligations.

But charter expansion really has been a key driver of declining enrollment in many places. A recent analysis found that in Los Angeles and San Diego, up to half of the district’s enrollment losses have been due to charter schools; in Oakland, it was up to three-quarters. (Right now, though, charter school growth is slowing nationally.)

In one Pennsylvania study, researchers estimated that school districts could recoup no more than 20 percent of the money lost to charter schools in the first year by cutting costs. In five years, they could recover no more than two-thirds.

Researchers looking at the issue in North Carolina, New York, Pennsylvania, and in two cases, California, have come to similar conclusions: As charters grow, the fixed costs of educating district students haven’t gone anywhere, even though the students have.

Some advocates have a particularly evocative term for those dollars: “stranded costs.”

There’s a big caveat, though: this logic only applies when the overall number of students in a district is flat or declining. If our hypothetical school district has a population of school-age kids growing fast enough to make up for the students leaving for charters, the expansion of charter schools might not hurt financially.

Charters may even help, if they allow district schools to keep existing seats filled while avoiding overcrowding and the need to build new schools. That may be one reason why some states that have seen the greatest population growth, like Arizona, Colorado, Florida, and Utah, have also seen charters boom.

Over time, it does seem like school districts adjust financially to charter growth — but the way they do so is controversial.

The calculus changes as years pass and districts adjust. In the long run, our hypothetical school district might raise taxes to prop up existing schools or close one of its schools to get average enrollment back up to 100 students per school.

“District schools are surviving but under increased stress,” noted one analysis of districts that have seen the greatest charter school growth. The study found that districts have substantially reduced costs as charters grew. After several years, there wasn’t much of evidence of increased class sizes, inefficiently small schools, or disproportionate overhead spending in those districts.

Another study of districts in New York (outside of New York City) that have seen significant charter growth finds a similar pattern. In the short run, charter schools add costs to the district — in this case, because district schools ended up with a greater share of low-income students and students with disabilities. Over time, though, the researchers found that districts became more efficient. In the long run, the rising costs and growing efficiency roughly canceled each other out.

The elephant in the room during these debates about charters: The most straightforward way for a district to cut costs when it loses students is to close schools.

There are other options, including raising taxes to maintain schools with fewer students (and there may even be benefits to having smaller schools). But that isn’t always possible. In many cases, school closures are the flip side of school openings.

A number of districts with lots of charter schools have gone through major rounds of school closures, including Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Washington D.C. (Take a look at Chalkbeat’s prior overview of research on school closures.)

In most cases, closures are fraught, with critics saying they create instability for kids and eliminate a community institution.

This debate is playing out in Oakland right now, a city where nearly a third of public school students attend a charter. The district has proposed closing a number of under-enrolled schools to cut costs, drawing vigorous opposition from striking teachers and many affected families.

When looking at academic results, it’s not clear that charter growth has hurt district school students. But more and better research is needed.

In some cities that have seen lots of charter school growth, like Chicago, students’ scores have been on an upward climb. In others, like Detroit, schools remain known for poor performance. That approach can’t isolate what effect charters are having, though.

Numerous studies have attempted to get at the effect of charter schools on the academic performance of district schools, not just their financial health.

In most cases, they find one of two things: Charters don’t have much of an academic impact or they slightly improve students’ scores at nearby district schools. That bolsters the theory of school choice advocates. (These studies usually look just at test scores.)

“Districts are stressed financially by the shifts of resources they must make in order to compete with charter schools, but not helpless,” wrote Paul Hill of the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Those studies usually only look at the district schools nearest to the charter schools, though, an approach that may miss the effects of charters on students throughout the district.

Take a 2017 study in New York City, which found that district schools actually scored higher on state tests after a charter school opened nearby. It’s possible that those schools stepped up their game to try to keep students in response to new competition.

But researchers also found something puzzling: those schools actually spent more money per student and lowered class sizes as a result of charter growth — likely because the district attempted to cushion the blow from declining enrollment with additional funding. For instance, the district is spending a projected $50,000 per student to keep open one elementary school with just 82 students.

The school, perhaps benefitting from that extra money, is doing well academically. But there is a steep cost of keeping such a school open, one that the rest of the schools in the district bear financially, and perhaps academically. That’s something existing research largely doesn’t address.

Another study found that in Massachusetts, test scores rose slightly in districts that saw charters expand. Again, though, that expansion came with additional money from the state to help districts adjust — a policy that exists in only a few other states.