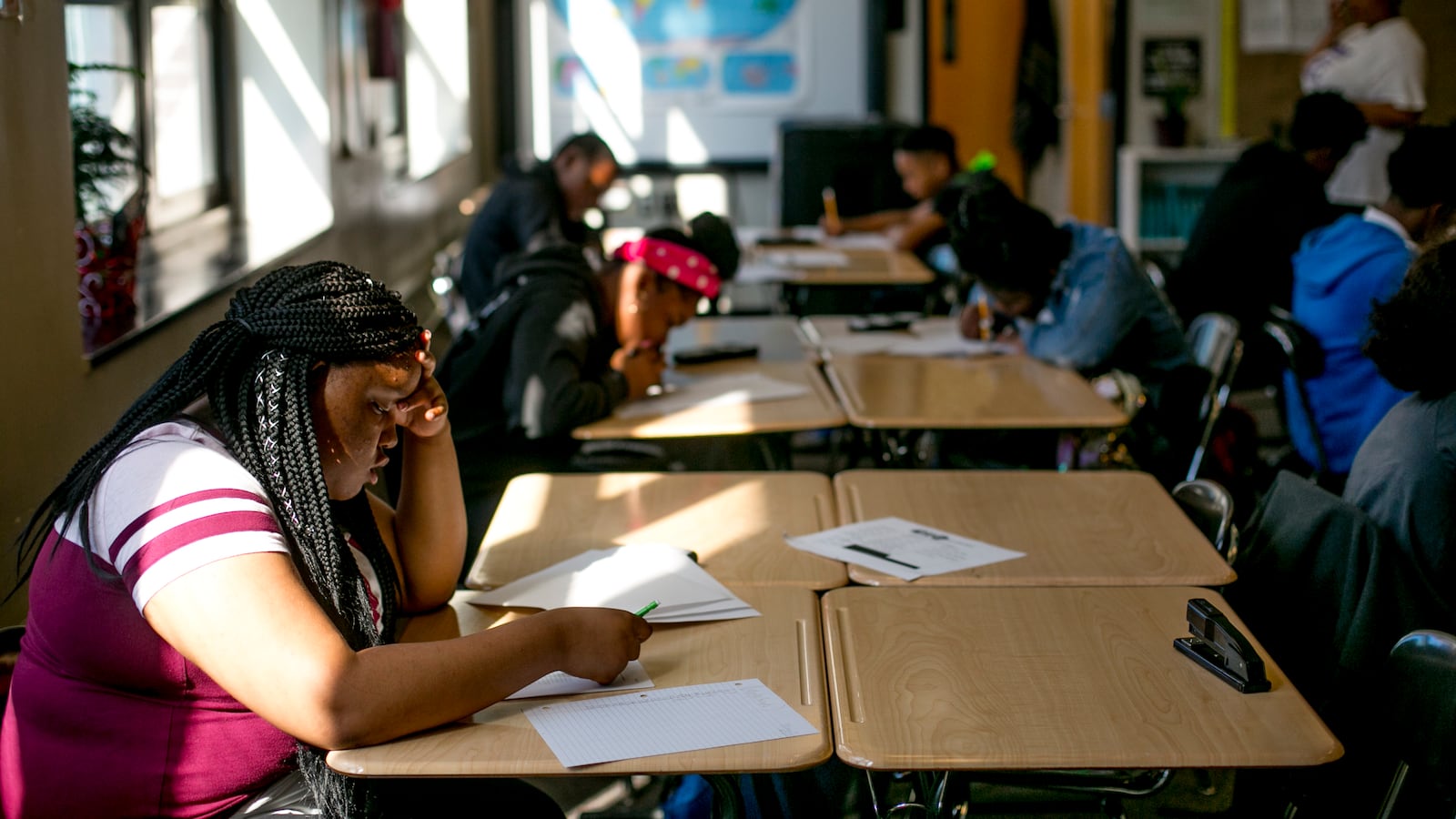

There is little talk today of improving education in Detroit through racial integration.

While cities like New York and Chicago have taken small steps recently to mix up their racially divided schools — acknowledging that in some neighborhoods, mostly-white schools exist not far from schools serving mostly students of color — in Detroit, nearly every student is black or Hispanic. White students are concentrated outside the district’s invisible boundaries, in suburban schools that surround the city.

Many have accepted this dynamic in Detroit and other communities across the country as a fact of life. But the stubborn persistence of those divisions can be traced back to Milliken v. Bradley, a pivotal Supreme Court case decided 45 years ago Thursday.

Though few know the case by name, it’s come to define how we think about school desegregation, particularly in the north.

The decision limited the courts’ ability to involve suburban districts in efforts to desegregate city schools unless it could be proven that they’d intentionally kept students out — an extraordinarily high bar. That made desegregation efforts that cross district lines exceedingly rare, and left some cities with few options to truly integrate their schools.

“The sorry state of racial integration in modern times can be understood as a major legacy of Milliken v. Bradley,” said Justin Driver, a professor at Yale Law School who has written about the impact of Supreme Court decisions on public school students. The Milliken decision, he said, meant that “the nation as a whole was not going to be required to pursue meaningful racial integration.”

Understanding Milliken v. Bradley is important as school desegregation continues to make national headlines in the wake of a tense exchange between Democratic presidential candidates Sen. Kamala Harris and former Vice President Joe Biden over the role of busing as a means to desegregate schools.

And a report released Thursday illustrates some of the ways those district boundaries continue to divide the country’s students by race and resources.

Some 8.9 million public school students — about one in five in America — live on the disadvantaged side of a particularly divisive school district boundary, according to the nonprofit EdBuild. Earlier this year, the organization documented a $23 billion state and local spending gap between schools that educate mostly white students and schools that educate mostly students of color.

EdBuild identified nearly 1,000 boundaries in 42 states where students of color are racially isolated from their peers and where their schools also receive substantially less funding. Schools on the whiter, wealthier side of those especially stark dividing lines receive an average of $4,200 more per student.

The school district boundary between Detroit and the nearby Grosse Pointe, for example, remains one of the most divided in the country. Three-quarters of Grosse Pointe’s students are white, and the district receives nearly $2,000 more per student in state and local funding than Detroit. Federal funds make up the gap.

“What you can see from the tragic history of Milliken is that when these areas are isolated by these borders that we draw, we further entrench over time both the segregation and the under-resourcing of schools,” said Rebecca Sibilia, the CEO of EdBuild.

How we got here

The Milliken v. Bradley case began in 1970 when the NAACP sued Michigan’s governor, William Milliken, and other top officials on behalf of a Detroit student. The NAACP argued that the state had intentionally segregated Detroit’s public schools through its housing policies, and should be obligated to desegregate them.

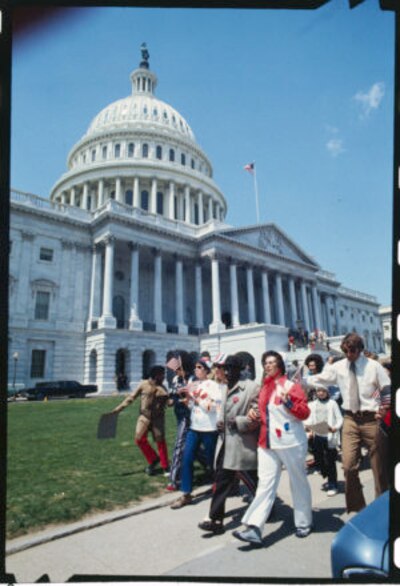

A district court judge agreed, and issued a metro area-wide desegregation order that included the mostly black schools in Detroit and 53 mostly white suburban districts. Suburban politicians and families organized against the plan, as they would elsewhere in the country. Sometimes these demonstrations led to violence: In a show of opposition to a similar busing plan, the Ku Klux Klan bombed a school bus yard in Pontiac, outside Detroit.

Some black political leaders also opposed the Detroit plan, pushing instead for more funding and increased local control in majority-black districts. That opposition was often rooted in fear over how black students would be treated, as past busing plans had required only black students to travel to mostly white schools, where they sometimes faced harsher discipline and harassment from their white peers.

But in 1974, the Supreme Court struck down the metro-Detroit desegregation order in a 5-4 ruling. It represented the first major departure from Brown v. Board of Education, a decision which declared 20 years earlier that racially segregated schools were unconstitutional, even if they were equal in quality.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Warren Burger argued that the suburban Detroit districts hadn’t encouraged the racial segregation, so they couldn’t be made to participate in a plan to fix it.

“The notion that school district lines may be casually ignored or treated as a mere administrative convenience is contrary to the history of public education in our country,” Burger wrote.

Civil rights advocates and scholars immediately recognized the far-reaching consequences of the decision. Justice Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American to sit on the high court, wrote in his dissent that the decision represented “a giant step backwards.” In a 1975 law review article, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, now a Democratic candidate for president, said the ruling would lead to more “separate and unequal” schools. And Detroit officials pointed out it did nothing to close the resource gaps between city and suburban schools.

“The basic issue remains, and that is the problem of unequal educational opportunity of racial discrimination, and of insufficient money to provide our children with quality public education,” Detroit’s mayor, Coleman Young, told a reporter in 1974. “That problem will not go away.”

Perhaps the most enduring effect of Milliken v. Bradley, experts say, has been the way it has cemented school district boundaries — “incentivizing white flight,” as Driver puts it, by shielding those in suburban districts from desegregation efforts.

In the years that followed, courts would issue 19 desegregation orders to districts across Michigan, including one in Detroit that didn’t involve the suburbs. But thanks to the Milliken ruling, it was easy for families to simply move to another suburb rather than take part.

“There is a way in which we look at Brown as an aspirational story that sets our national narrative along a long arc toward more freedom and justice and equality,” said Brett Gadsden, a history professor at Northwestern University. “Milliken tells the opposite story.”

What it means now

In 2019 as in 1974, the education Detroit-area students receive continues to differ, depending on their skin color and their neighborhood.

Tensions also persist between the city and the suburbs. A few years ago, the suburb of Grosse Pointe Park built a barrier along its border with Detroit, surfacing old concerns about racial segregation. (It now appears poised to come down.) Voters in Detroit’s northern suburbs also recently rejected a plan to knit the metropolitan area together with a regional transit system. One of the most vociferous critics of the project was L. Brooks Patterson, who rose to prominence fighting against the regional busing plan.

Just 2 percent of students in the Detroit district today are white. And while some hoped that Michigan’s generous school choice policies would offer some of the same benefits as busing by making it possible for families to cross district lines, longstanding patterns of segregation show no sign of disappearing, in part thanks to continued white flight.

In East Detroit, a district on the city’s northern border that saw a recent influx of black students, white enrollment dropped from 50 percent to just 18 percent between 2009 and 2015.

“Those with the wherewithal, usually the white population, are opting out of these schools,” said Kurt Metzger, a demographer and the mayor of Pleasant Ridge, a city in suburban Detroit. “And there isn’t a whole lot of discussion about it. They aren’t going to say it racially, they’re going to say the test scores aren’t good enough.”

Such extreme segregation would be hard to imagine if Milliken v. Bradley had gone the other way, said Joyce Baugh, author of “The Detroit School Busing Case” and a professor emeritus at Central Michigan University.

“If folks were told, ‘This is what you have to do,’ some of those people would have moved, I’m sure,” she said. “But not everybody.”

To Baugh, less racial segregation would also have guaranteed a more even distribution of resources to districts across the state.

“The white folks who had to send their kids to black schools would have been more inclined to push the legislature. I just can’t imagine that if their kids had to go to those schools in Detroit, they wouldn’t have done everything they possibly could to make sure that those schools had all of the resources that they needed.”

To be sure, since Milliken there have been numerous efforts to make up for funding inequities between districts, in Michigan and elsewhere. Many states faced successful lawsuits arguing that districts serving low-income students of color weren’t receiving their fair share — and subsequent research showed that influx of money directly benefited students.

The federal government has also chipped in to try to address disparities. Detroit gets substantially more federal dollars than Grosse Pointe, more than making up for the disparity in state and local money — though the federal government has warned that its money shouldn’t be used to justify unequal funding at the state and local level. On average, Michigan spends around $180 less per student in districts that enroll mostly students of color, according to EdBuild.

Despite efforts to fill the gaps, urban districts across the state continue to struggle financially and academically. But 45 years after Milliken, proposals to help them seldom touch on desegregation — a consequence of that Supreme Court decision and later ones that have further limited how school districts can use race to assign students to schools.

“To me, that’s ancient history,” said Keith Williams, chair of the Michigan Democratic Party Black Caucus, who was bused to a majority-white school in Detroit as a child. “It’s about improper funding of the schools.”

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, has proposed a budget that would move toward a funding system that sends more money to districts with more high-needs students like Detroit. The idea shows no signs of gaining traction in the Republican-controlled legislature, where lawmakers have remained focused on finding money to repair the state’s crumbling roads.

“It would be nice if [white people] wanted to be my neighbor,” Williams says. “I still think we’ve got to live amongst each other and work together.”

But in the end, Michigan’s continued racial segregation bothers him less than the lack of political will to change how the state funds schools — moves that would especially benefit black students. “My problem is,” he said, “don’t take my resources.”

Kalyn Belsha reported from Chicago and Koby Levin reported from Detroit.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the difference in federal funding received by Detroit and Grosse Pointe.