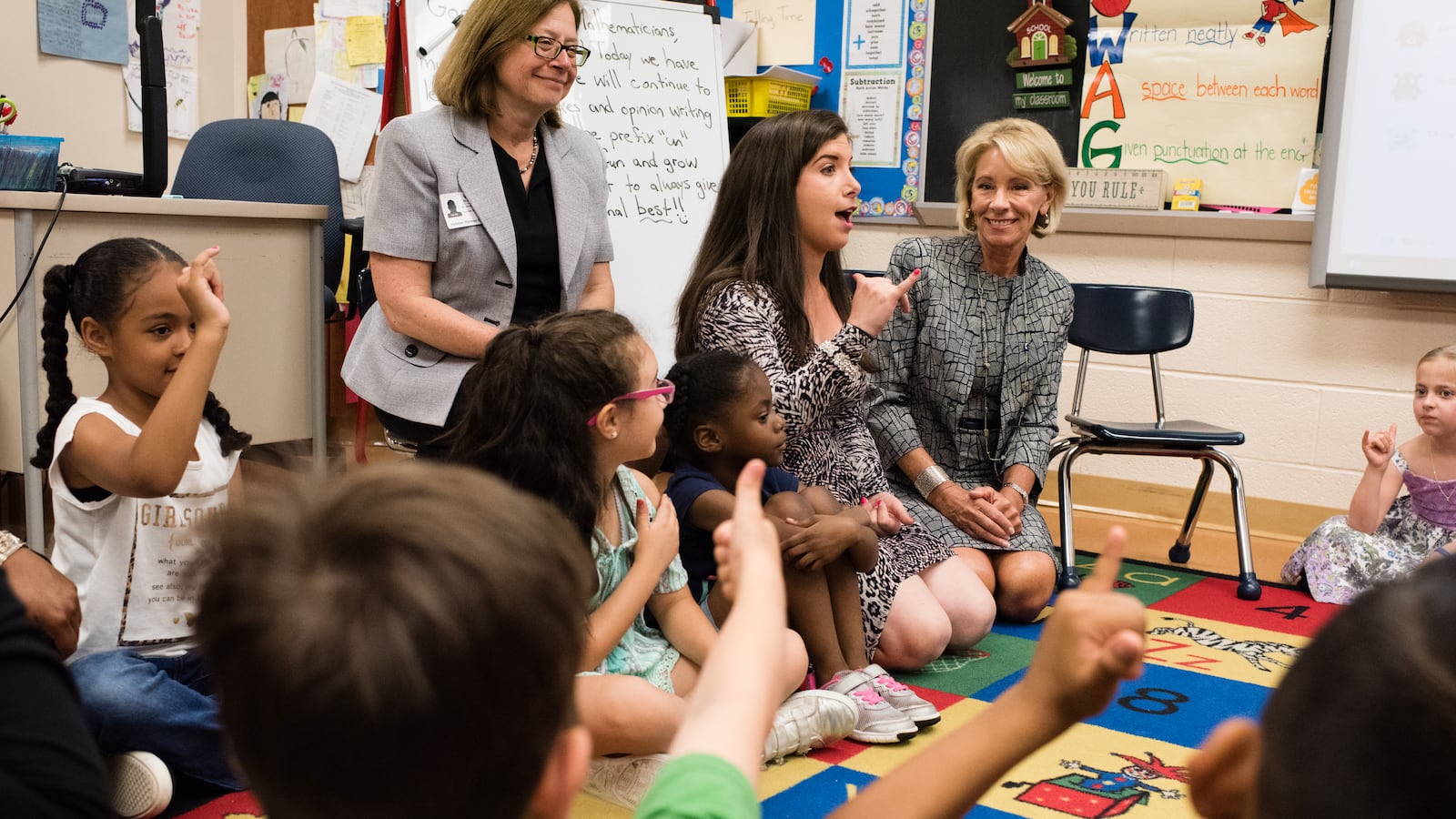

Why are so many teachers scrounging for school supplies? While touring a private school in Milwaukee on Monday, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said it comes down to how school districts are spending their money:

The education cabal puts other issues above what’s right for students. Mixed-up priorities are borne out in the numbers. Consider that American taxpayers spend — on average — about $13,000 per student, per year. With an average class size of 21 students, that adds up to $273,000 per classroom, per year. We know the average classroom teacher makes about $60,000 annually. So, where does the rest of the money go? More than $200,000 per classroom and teachers are still buying school supplies out of their pockets. Well, here’s the dirty little secret: it’s to highly paid administrators, coordinators, consultants, assistant principals, assistant superintendents—layers and layers of bureaucracy. The growth in non-instructional school staff has increased nine times faster than student enrollment growth. It just doesn’t add up.

DeVos’ arguments highlight her long-standing skepticism of the educational establishment and of spending more money on schools. But is she right?

There’s a lot to unpack here, but the short answer is no, administrators don’t account for a particularly big slice of school spending.

The latest school spending data, collected by the Census Bureau, shows that only 7.4% of schools and school districts’ operating costs go to administration. DeVos’ own education department pegs administrative costs at 6.7% of total spending, a figure that hasn’t changed much in many years.

One can certainly argue that less money should be spent on administration, but it’s not eating up a large share of education dollars.

DeVos is right that the number of non-teaching school staffers has risen over time, and risen faster than the number of teachers and students. But much of that increase happened decades ago, likely in part because of efforts to better accommodate students with disabilities.

Here’s where the money really goes.

Most education dollars go to instruction — chiefly, the salaries and benefits of teachers and aides

Let’s start with the basic facts about where education dollars go. Earlier this year, the Census Bureau found that U.S. public schools spent an average of $12,201 per student in 2017. (This does not include capital spending on things like new school buildings.)

Of this, the majority — 61% — went to instruction, which is predominantly the salaries and benefits of teachers and instructional aides.

Most of the remainder — 35% — goes to what is categorized as “support services.” This includes support for students like social work and counseling (5.9% of total spending), school administration (5.5%), support for teachers, like curriculum development and training (4.7%), and central office administration (1.9%). That bucket of funds include transportation and building maintenance, too.

So why doesn’t DeVos’ initial example, using teacher pay and class size to suggest that the lion’s share of school spending is being spent on bureaucrats, add up?

A few reasons. She doesn’t include the costs of teacher benefits, which are an important part of teachers’ compensation. That average teacher costs a district more than $60,000.

There are also more teachers serving those 21 students than the one at the front of the class at a given moment — art teachers and special education teachers, for example. (There are about 16 students per teacher nationally.) DeVos is also excluding teachers aides, who play a role in classroom instruction.

In response to a question about DeVos’ figures, a spokesperson pointed to a blog post from a free-market think tank in Wisconsin that argues that too much money goes to expenses other than instruction. But that data also shows that administration only accounted for 7.7% of school spending, while 54% went to instruction.

The number of non-teaching school staffers has increased over time, but much of that increase came decades ago

DeVos also took aim at the growth of non-teaching school staff. U.S. Department of Education data shows their numbers have been rising, especially if you look over many decades.

In 1970, just 40% of school staff were not teachers. By 2015, 50.6% of staff employed by schools and districts were not teachers. To DeVos, that’s evidence of today’s bloated corps of non-teaching staffers.

But much of that jump in non-teaching staff came between 1970 and 1980. And many of those new staffers weren’t administrators but instructional aides, likely because of increased efforts to accommodate students with disabilities in public schools. In 1970 there were an estimated 57,000 instructional aides in schools; by 1980 there were 325,000 and by 1999 more than 600,000. (An additional wrinkle is that data from 1980 and before is only “roughly comparable” to numbers from later years.)

The most common non-teaching job in schools has long been “support staff,” which is nebulously defined. Today they account for 30% of jobs in schools, a share that has barely budged since 1990.

What about “highly paid administrators”? They’re simply aren’t that many of them. Principals and assistant principals make up 2.9% of school staffers, while school district administrators are just 1.1%. Neither share has changed much in recent decades.

There has been a significant increase in “instructional coordinators” in recent years, but they account for only 1.4% of school staff.

A Fordham Institute report, using more detailed data from Florida, found the most common non-teaching jobs in schools were aides, custodians, bus drivers, food service workers, clerks, and secretaries — all jobs that pay substantially less than teaching.

So where did DeVos’ claim that “the growth in non-instructional school staff has increased nine times faster than student enrollment growth” come from? The same federal data we previously cited, according to a spokesperson.

DeVos mangled the stat, a bit: she says she was referring to “non-instructional staff,” but those numbers include teachers and instructional aides. She is still right that there are more adults — teachers and especially non-teachers — per student in schools compared to 1970.

Again, though, most of that growth happened many years ago. In 1970 there were 13.6 staff members per students; by 2000 there were 8.3. Recent data shows the number hasn’t changed much since. In 2015, there were 7.9 staff members per student, about half of them teachers.

Finally, it’s worth considering DeVos’ implication that money not spent directly on teachers is inefficient or even a waste.

Charter schools, which DeVos is a fan of, tend to spend a greater share of their money on administration than district schools, though there’s not much evidence that causes them to perform worse. Meanwhile, there is research linking many non-teaching staff — teaching aides, school counselors, principals — to better outcomes for students. That suggests that they can and often do play a valuable role in schools.