If the 25,000-plus members of the Chicago Teachers Union strike later this month as planned, it might not be over salaries, but about a host of other issues union leaders have brought to the bargaining table.

In addition to higher pay and lower class sizes, Chicago’s union is also asking for the city to expand “community schools” that offer wraparound services; increase the numbers of social workers, school nurses, and librarians; and support more affordable housing.

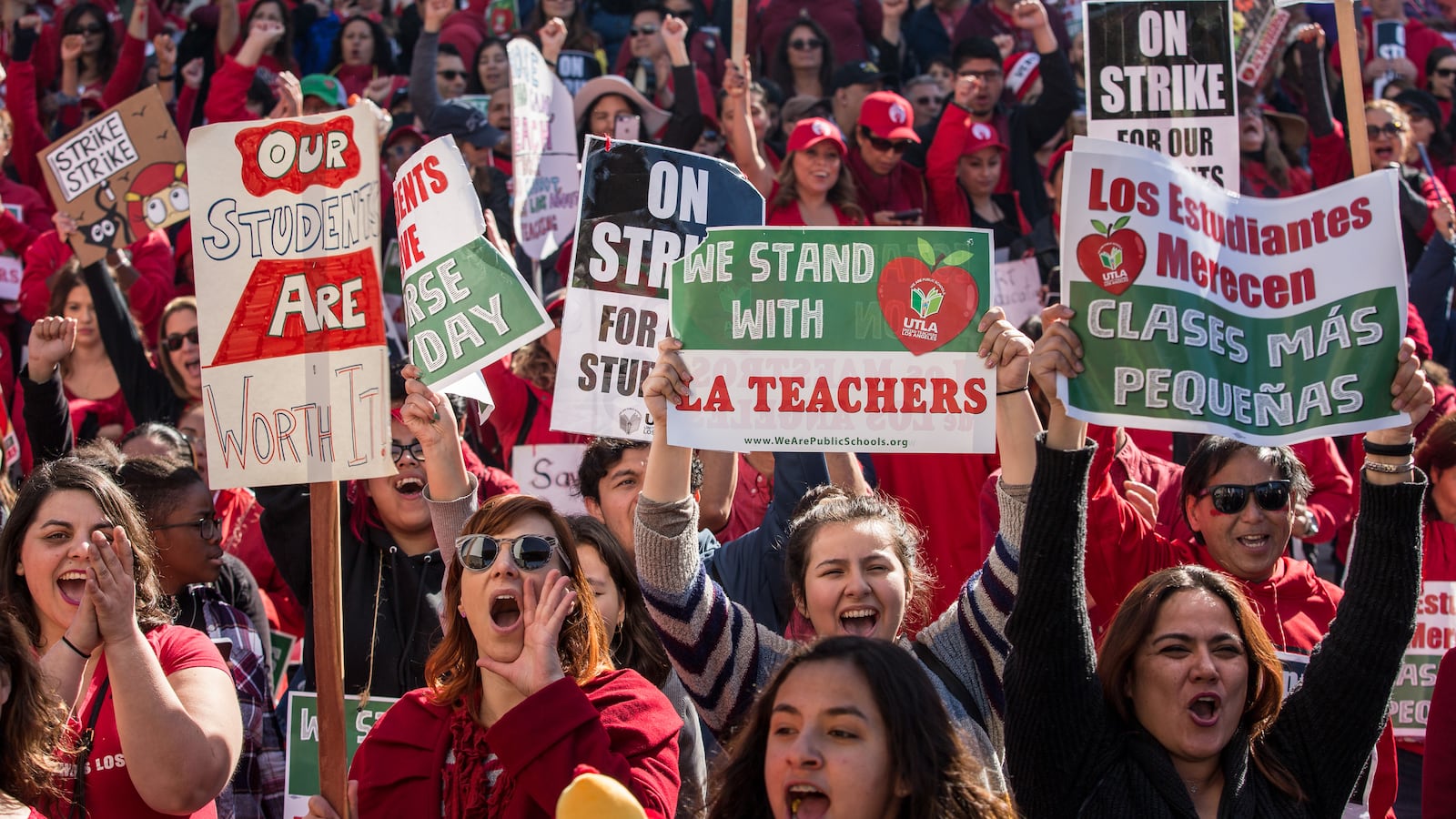

Los Angeles teachers had several similar demands, and won some after going on strike for six days in January, including immigration help for students and more nurses and counselors. That reflects a shared philosophy known as “bargaining for the common good” that’s been gaining prominence nationally.

Under this approach, unions bring demands to the table that affect students or local communities, even if the unions don’t have the explicit power to bargain over them — using the fight over a pay agreement to pressure districts or cities to make changes. The unions often work to get community advocates involved, too.

“This is the trend of taking things that obviously affect working conditions, and obviously affect learning conditions … and demanding to bargain on them,” said Alex Caputo-Pearl, who heads the United Teachers Los Angeles. That’s a similarity “not only between the Chicago and L.A. struggles, but really about where the national teachers union movement is heading.”

It’s been especially visible since both cities elected educators who made social issues a core part of their platforms to lead their teachers unions. In Chicago that began with the 2010 election of Karen Lewis, who came from a group within the union known as the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators. In Los Angeles, the analogous Union Power caucus came to power in 2014.

Union leaders in those cities say they have been in close contact with one another over the years, watching and borrowing from each others’ work.

How rapidly the strategy is spreading is unclear. Teachers who have gone on strike or walked out over the last two years in states like West Virginia, Arizona, and Oklahoma have also focused on how the issues at stake affect students and families. But they’ve also needed to be seen as nonpartisan as they sought support from lawmakers for raising teacher pay and education funding. Chicago and Los Angeles teachers, by comparison, have bargained in Democrat-led cities where teachers earn higher salaries.

But some 50 unions and other groups are part of a network that supports bargaining for the common good. They include the country’s two largest teachers unions — the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers — as well as three state teachers unions and local teachers unions from Milwaukee; Seattle; Saint Paul, Minnesota; and Dayton, Ohio; in addition to Chicago and Los Angeles.

In Los Angeles, union leaders say this approach led to meaningful wins, including provisions in the new teachers contract that said the district would pay a lawyer to help students with immigration-related concerns and expand a pilot program that curtails random searches of students, something Caputo-Pearl said has led to racial profiling. That was in addition to a 6% pay raise — an offer that didn’t change with the strike — modest class size reductions, and increases in the number of nurses, librarians, and counselors.

The approach, though, raises questions of what gets defined as the common good and how much those demands usually cost. The Los Angeles strike, for one, turned on a disagreement about how much the school district could afford.

In Chicago, teachers want the school district to declare its support for expanding affordable housing for teachers, students, and their families. That’s notable at a time when parts of the city have seen rapid development while other parts have suffered from decades of disinvestment.

Meanwhile, the city has criticized that demand as inappropriate, saying it wants to deal with the issue outside the bargaining process.

“Affordable housing is a critical issue that affects residents across Chicago, and everyone’s voices need to be heard during this process,” Mayor Lori Lightfoot said in a statement Tuesday. “As such, the CTU collective bargaining agreement is not the appropriate place for the City to legislate its affordable housing policy.”

Lightfoot has offered the union a 16% pay raise over five years — a deal some observers have called generous and reflective of the city’s financial standing, which is stronger than it was when the union went on strike in 2012 and when it led a one-day walkout in 2016.

But the Chicago union also wants more staff and smaller class sizes. The mayor has verbally agreed to add hundreds of social workers, nurses and special education case managers over the next five years, but union leaders want the offer in writing. The district has class size guidelines for elementary school grades, but schools routinely exceed those amounts.

“If you’re in Chicago now, and obviously there’s a longer local history there that’s important, but you see what Los Angeles teachers were able to accomplish, and win, then it makes it much more likely that teachers in Chicago are also going to broaden their tactics,” said Jon Shelton, an associate professor of history at the University of Wisconsin Green Bay who wrote a book about teachers unions.

Stacy Davis Gates, the vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union, notes that both Los Angeles and Boston teachers won increases in the number of nurses in their contracts this year. She sees the nursing request as especially necessary for students from low-income Chicago families who often can’t afford or access quality medical care in their community.

“Seeing thousands of people … demanding a better day for L.A. students, you can’t help but be inspired by that,” she said. “It helps to have company, it helps to have an echo chamber.”

The staffing levels of nurses have been a persistent concern in Chicago. An investigation by the city’s NPR affiliate WBEZ earlier this year found that none of the district’s more than 500 schools had the same full-time nurse all day. The Chicago Sun-Times, meanwhile, has documented parents staying home with their children because the district didn’t provide a nurse.

“We see our contract as the one thing that is enforceable, that can bring equity, that can bring justice, into our school communities,” Davis Gates said.

Still, the Los Angeles union’s experience also points to the risks a strike could pose for Chicago teachers. The most important one: walking out for an extended period could alienate the low-income parents of color least able to afford child care when school isn’t in session.

In Los Angeles, the district kept schools open with limited staffing during the strike, though many parents kept their children home. Some struggled to find alternative child care.

In Chicago, district officials have promised to keep schools open and to feed students meals if teachers go on strike. That could be complicated, though, by two other strikes being planned by school support staff and park district employees, who have helped care for students in the past.