Results of the national NAEP test aren’t always predictable, but the responses from education leaders and pundits usually are.

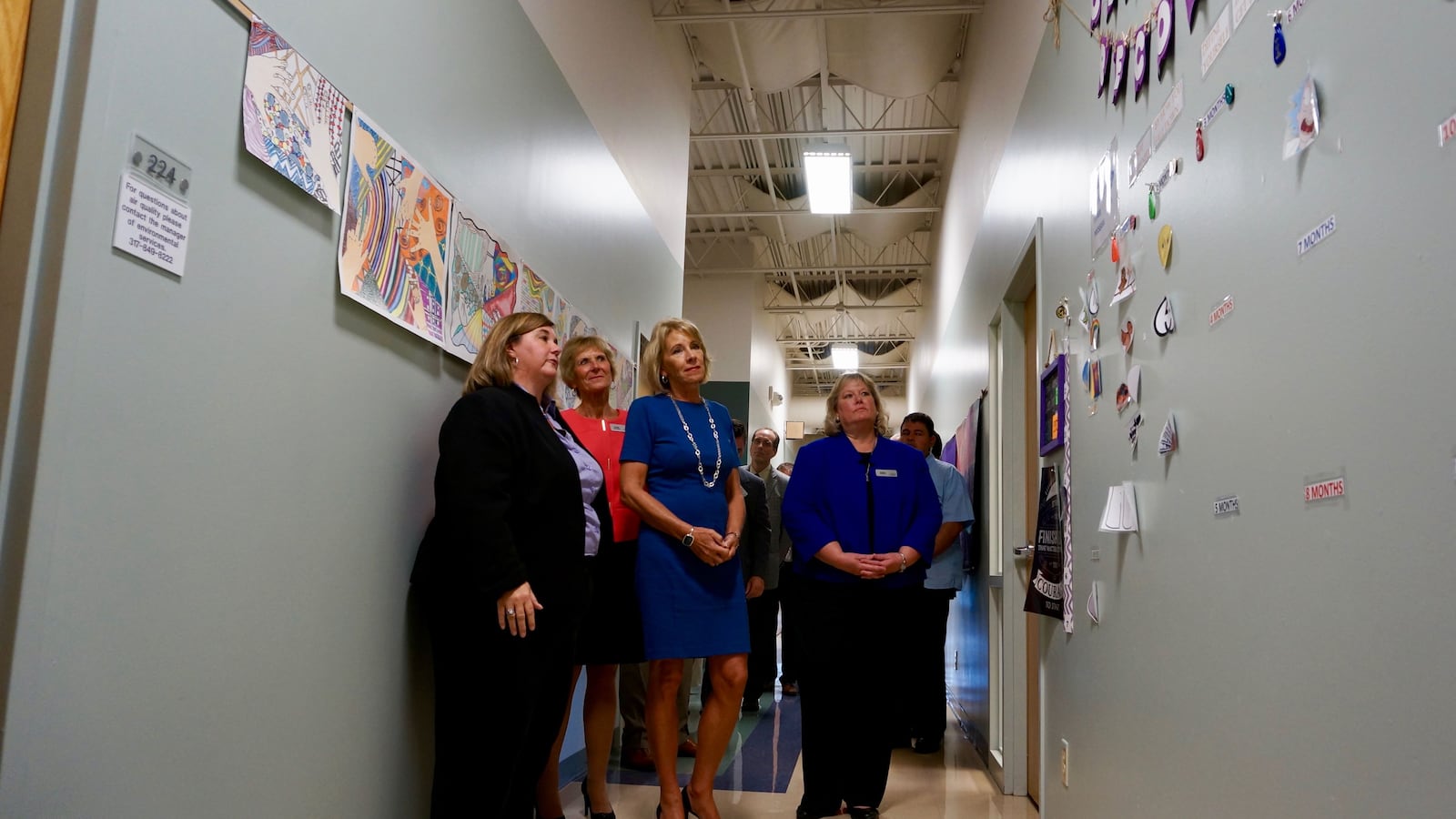

Many use the scores to make the case for their favored policies, even as researchers caution against connecting the test results to specific reforms. On Wednesday afternoon, it was Secretary Betsy DeVos who used the grim results on the “nation’s report card” to push for more school choice and less federal involvement in education in a speech at the National Press Club.

“This country has a student achievement crisis,” said DeVos. “It’s time to try something new. We need to pivot to a policy of freedom. Put improving student achievement in this country above all else — above any system, any mechanism, any building, and importantly, above politics.”

DeVos highlighted improvements in Mississippi, where she credited a law that holds back struggling readers, and pointed to a long-time favorite, Florida, where she emphasized the expansion of charter schools and vouchers.

But the call for more school choice — which, alongside deregulation of education at the federal level, DeVos has rebranded as “education freedom” — in response to stagnant test scores is certain to spur debate.

Research has generally found that charter schools perform comparably to district schools on state exams, with those in cities performing better and online charters performing worse. There is some evidence linking the growth of charter schools in cities to rising test scores across the board.

But recent studies on three voucher programs that subsidize private school tuition have shown that they reduce test scores in math. (DeVos has previously blamed over-regulation for Louisiana’s results.) In D.C., voucher recipients did about the same as public school students test-score wise, according to a recent study.

In response to these studies, a number of school choice advocates, including DeVos, have downplayed the importance of test scores. “We get focused on academic outcomes exclusively and often parents make choices for other reasons,” she said in May.

In her speech, at the National Press Club, though, DeVos leaned into the latest test score results, saying they revealed that states need to make dramatic changes.

“Today’s Report Card is essentially the same as the last one, and the one before that, and the one before that. In fact, student achievement hasn’t changed much since 1992,” she said. (Fourth- and eighth-grade math scores did improve substantially between 1990 and 2009, a fact DeVos partially acknowledged.)

DeVos’ also argued that education dollars aren’t being directed to students, but instead to building and highly paid adults. Specifically, she reprised her claim that since 1950, education dollars have increasingly gone to highly paid administrators and non-instructional staff. It’s true that the share of non-teaching staff has grown, especially looking back many decades, likely in part due to the increase of aides for students with disabilities. There is little evidence that schools are spending more on administration, though.

Critics on the other side of the ideological fence seized on the NAEP scores, too.

“After a generation of disruptive reforms — No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top, VAM and Common Core — after a decade or more of disinvestment in education, after years of bashing and demoralizing teachers, the National Assessment of Educational Progress for 2019 shows the results,” wrote Diane Ravitch, the education activist and historian.

Meanwhile, politicians and education leaders in the few states that saw gains celebrated the results, sometimes attributing the gains to specific policies. But researchers warn against that practice because many factors in and out of school might explain changes in NAEP scores.

That doesn’t mean that NAEP scores can never help evaluate policy. Trends can generate hypotheses on what is working and what isn’t, and using careful statistical techniques, researchers have worked to isolate the impact of specific reforms.

A number of studies have found that tougher test-based accountability rules, including No Child Left Behind, raised NAEP scores in math. Another recent study found evidence that the introduction of the Common Core standards reduced NAEP achievement.

Two studies have also linked more resources for schools to higher NAEP scores — though DeVos suggested otherwise Wednesday.

“Over the past 30 years, per-pupil spending has skyrocketed,” she said. “A massive increase in spending to buy flatlined achievement.”

One study showed that school finance reforms that resulted in more money boosted scores, and another found that education cuts in the wake of the Great Recession led to lower scores.