In a recent study, a high school counselor offered this honest description of the uncertainty of her job: “Maybe later, I’ll start to see kids come back and they’ll be like, oh this helped or that helped,” she said. Still, “Sometimes I leave and I’m like, I’ve done nothing.”

Now, new research captures exactly how much of a difference a counselor like her can make — and it’s substantial, particularly for low-income students.

That study appears to be the first to quantify how individual counselors affect students. Better counselors boost students’ chances of graduating high school and enrolling in and remaining in college, it finds. And students of color do much better when assigned to a counselor of color, seeing their chance of graduating high school jump nearly 4 percentage points.

It comes as a number of other efforts to improve low-income students’ chances of enrolling and persisting in college have produced uneven results — suggesting the basic approach of adding counselors or helping existing ones improve deserves more attention.

Christine Mulhern, a Harvard graduate student, said she undertook the study because prior research on school counselors was so limited, but she suspected they made a big difference. “Talking to a lot of people, they said that their own school counselors had a big role in what they ended up doing,” she said.

Mulhern’s research was made possible by a key insight: Students are often assigned to counselors alphabetically by last name. Because alphabetization is essentially random, Mulhern — armed with a massive dataset from the state of Massachusetts — was able to study how more than 500 counselors affected the outcomes of nearly 150,000 students over a number of years.

Her first major finding was that counselors vary in their ability to improve students’ trajectories.

Students who had a counselor of far-above-average quality were 2 percentage points more likely to graduate from high school, 1.5 points more likely to attend college, and 1.4 points more likely to stay in college through their first year.

These effects were even larger for low-income students, students of color, and lower-achieving students. For instance, a very good counselor improved low-income students’ high school graduation rate by 3.4 percentage points and college enrollment by 2.9 points.

Students of color also benefited from having a counselor of color. Their chances of graduating high school and attending college each increased by 3.8 percentage points — an effect even bigger than having an above-average counselor.

However, 87% of counselors in Massachusetts were white, according to the paper. There does not appear to be recent national data on the demographics of public school counselors, but a 2011 survey found that about three quarters were white.

Surprisingly, considering research on teachers, more experienced counselors were no more effective than novice ones. Individual counselors’ ability was fairly consistent from year to year.

Mulhern’s research is similar to widely cited studies on teachers, which have shown that some are better at raising student test scores, and other outcomes like attendance, year over year. This line of work proved controversial, though, after it became the intellectual basis for tougher teacher evaluation systems that relied in part on student test scores.

Mulhern, for her part, is skeptical that policymakers should rush to implement new evaluations for counselors on the basis of her work.

“There are a lot of things counselors are supposed to be doing that I can’t measure, [like] mental health support,” she said. “I’m not sure that I want these measures to be used in evaluation, but at the same time, I think students can benefit a lot if schools can identify effective counselors. There may be some middle ground where more training is targeted to people who don’t seem to be doing as well as their peers.”

Meanwhile, a number of policymakers and philanthropists have focused on ways to boost high school students’ college attendance — without the help of school counselors. Those lower-cost efforts include packets of information mailed to high-achieving high schoolers, text messages to remind students to fill out financial aid forms, and virtual advisors to help them through college applications.

These efforts have generally had modest impacts at best. Mulhern’s research suggests a different tack: improving the quality or quantity of college counselors.

“This can work, and there’s already this huge infrastructure — all of these training programs, this whole profession devoted to this,” she said. “It may be useful to think of this problem from the perspective of individuals who have already been working on it for a long time.”

Mulhern research doesn’t provide clear insight on how to improve counselor effectiveness. But it does suggest — in line with past research — that hiring more counselors could help. She finds that at an average school hiring a new counselor would increase the entire school’s graduation rate by about half a point and college enrollment by nearly a full point. The benefits are even larger for low-performing students.

A separate recent paper on the experience of college counselors in an unnamed urban school district — which enrollment data suggest is Milwaukee Public Schools —offers a window into why.

Sometimes, counselors describe their job as providing optimism when students are down. “I think I’m still a safe place for them to go to,” one counselor explained. “I’m their cheerleader, trying to tell them you can do it, you’re okay. I’ll help you. What can we do?”

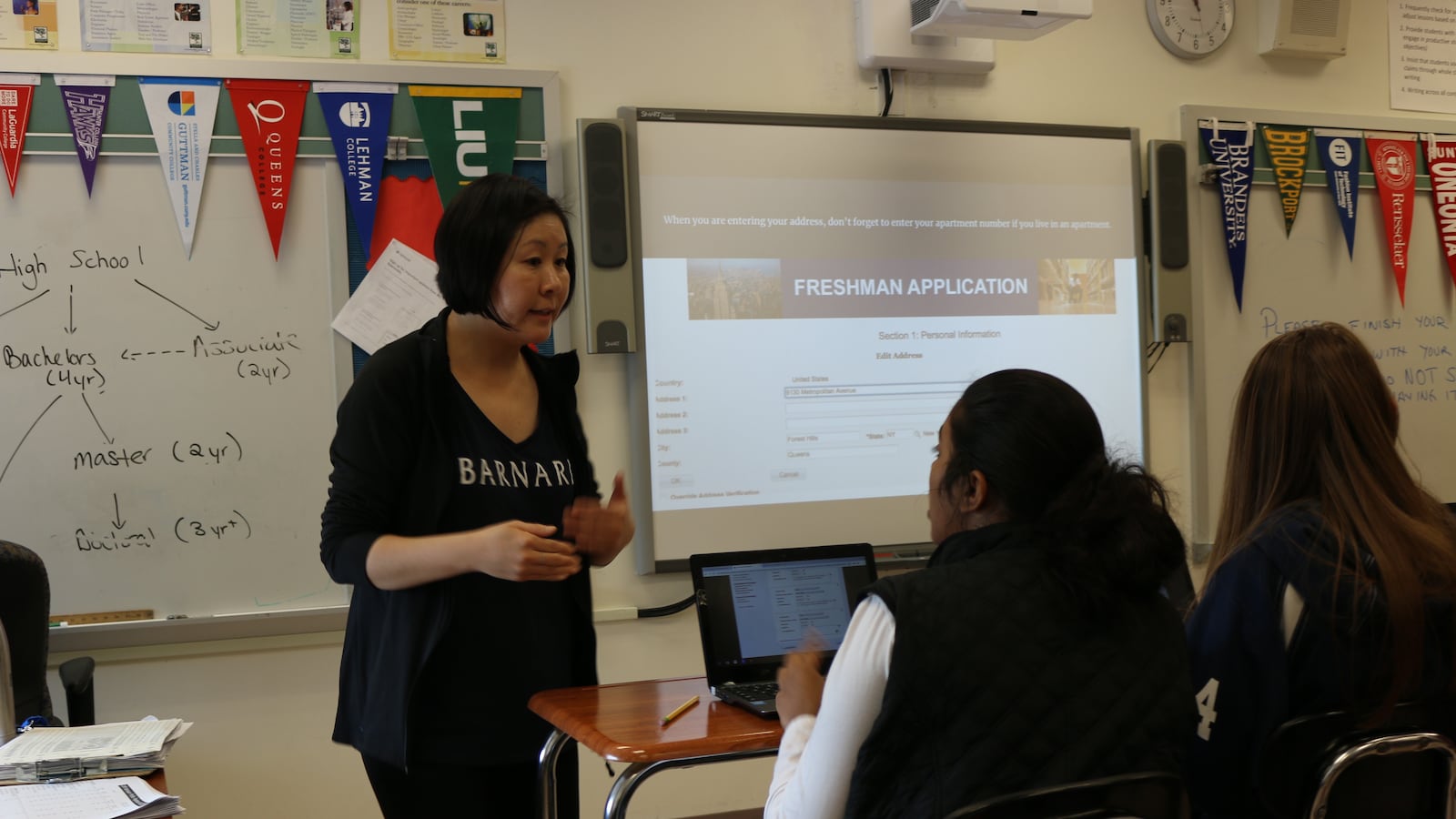

Other counselors describe focusing on helping students make post-high school plans. “Are you planning to go to college? Do you want to go to [the] military? What’s your plan? That kind of intimidates them,” one counselor described. Several said an especially delicate aspect of the job is trying to support students’ ambitions while providing realistic advice.

But for counselors, there are also more things to be done then time to do it. Many described being pressured to take on additional responsibilities, including coordinating standardized testing. In Milwaukee, one counselor is responsible for more than 300 students; in Massachusetts, the ratio is slightly lower.

“Typically in schools you have stuff popping off all day. So, you are responding to crisis,” one counselor told researchers. “I try to have a plan as much as I can … But sometimes you don’t get anything done in your plan.”